1.1 Recurring images in the media

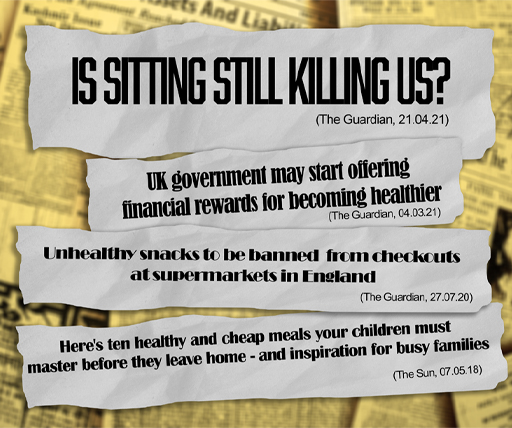

One key set of concerns that recur in media coverage and public discussion is in relation to young people's physical health and is often encapsulated in the popular media image of the young person as a ‘couch potato’, eating too much (and too much of the wrong things) and not getting enough exercise. Figure 1 shows a typical selection of recent headlines/podcast content from two UK newspapers, reflecting some of the contrary views on the issue.

The image of the unfit and overweight teenager has become a staple of anxious multimedia coverage and of popular cultural representation. The picture that comes to mind is of a young person slumped on the sofa in front of a TV screen, phone or tablet, or hunched over a PlayStation, snacking on unhealthy food, rarely going out into the fresh air or taking part in physical activity.

A second and increasingly pervasive image is that of the anxious teenager. Concern about young people's emotional wellbeing has grown in recent years, with a number of research studies claiming that there has been an increase in mental health problems among young people.

In 2020, about three quarters of children aged 5 to 16 years in the UK were identified as unlikely to have a mental disorder. However, in the same year, one in six (16.0%) children of the same age in England were identified as having a probable mental disorder. This was an increase from one in nine (10.8%) children in 2017, which has been offset by a decrease in the proportion identified as having a possible mental disorder between the two periods (13.7% in 2017 to 9.6% in 2020) (NHS Digital, 2020).

UK general practitioners think that mental health services for children and young people are inadequate, a survey has found. The survey of 1000 UK GPs found that 99% feared that young people may come to harm while waiting for specialist mental health treatment from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). The survey, conducted on behalf of a mental health charity, found that 78% of GPs were worried that not enough of their young patients could access treatment for mental health problems (Rimmer, 2018).

Taken together, these images – of the young person as physically unfit and anxious – tell a story of an alarming decline in the state of young people's wellbeing. But how does this ‘story’ – reproduced in the media and increasingly in policy discussions – account for this apparent decline?