From patronage to the open market

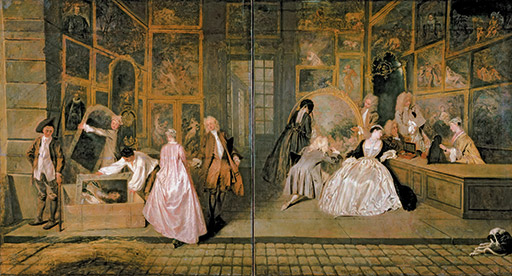

Nevertheless, the period after 1600 saw a shift away from patronage towards the open market. This shift accompanied the gradual decline of ‘sacral’ and ‘courtly’ art, both of which were normally executed on commission. Consider the case of Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin, an altarpiece commissioned for the church of Santa Maria della Scala in Rome in 1601 (Figure 8). In the event, the resolutely human terms in which the painter depicted the subject and the unidealised treatment of the figures scandalised the monks responsible for the church. The painting was therefore put up for sale, exciting intense interest among artists, dealers and collectors; it was snapped up (at a high price) by the Duke of Mantua, on the advice of Rubens, who was then employed as the duke’s court painter (Langdon, 1998, pp. 246–51, 317–18). Thus a functional religious artefact was transformed into a secular artwork, acclaimed as a masterpiece by a famous artist and sold to a princely collector, for whom the possession of such a work was a matter of personal prestige. The comparable transformation of courtly art in response to the market can be illustrated by reference to another picture immediately displaced from the location for which it was painted. In 1721, the Flemish-born artist Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) painted a large canvas as a shop sign for his friend, the Parisian art dealer Edme Gersaint (Figure 19). It shows the kind of elegant figures that the artist typically painted, but here, rather than engaging in aristocratic leisure and dalliance in a park-like setting, they are scrutinising items for sale in an art dealer’s shop; a portrait of Louis XIV is being packed away into a case, as if to mark the passing of the era of grand courtly art. Rapidly sold to a wealthy (though not aristocratic) collector, Gersaint’s Shop Sign exemplifies the way that Watteau repackaged courtly ideals for the market to reach a wider audience. The painting also shows how art collecting became a refined pastime for the social elite, in which art dealers played a crucial role (McClellan, 1996).

As these two examples demonstrate, more market-oriented structures and practices emerged in countries such as Italy and France from the end of the Renaissance onwards (see Haskell, 1980; Pomian, 1990; Posner, 1993; North and Ormrod, 1998). However, the tendency towards commercialisation is even more striking elsewhere: for example, in the growth of large-scale speculative building in late seventeenth-century London. As already noted, the emergence of ‘bourgeois art’ (as distinct from architecture) is best exemplified by the Netherlands, where most artists produced small easel paintings for sale. This model of artistic practice went hand in hand with the rise of art dealers and other features of the modern art world, such as public auctions and sale catalogues (see Montias, 1982; North, 1997; Montias, 2002). In important respects, the Dutch case remains idiosyncratic, but nevertheless the genres of painting that dominated in this context – that is, portraiture, landscape, scenes of everyday life and still life – soon became the most popular and successful elsewhere in Europe too. It was not just subject matter that counted, however; increasing emphasis was also placed on the distinctive brushwork of the individual artist and on the skills of connoisseurship that both dealers and collectors needed in order to recognise and appreciate the ‘hand’ of each ‘master’ and, of course, to distinguish genuine works from misattributed ones and outright forgeries. Exemplary in this respect is the work of Rembrandt; it was thanks above all to his exceptionally broad and hence highly distinctive handling of paint that he came to be generally regarded as the greatest of all post-Renaissance artists by the mid nineteenth century (see Figure 17). As a result of these developments, painting increasingly tended to overshadow other art forms, especially tapestry, which lost its previous high status with the decline of courtly art. However, Neo-classicism in general and the career of Canova in particular temporarily boosted the status of sculpture around 1800 (Potts, 2000; Lichtenstein, 2008).