1.1 The new art history

After the Second World War, art history tended to involve a mix of antiquarianism, connoisseurship and liberal humanist values that incorporated some of the idealist notion that art is a reflection of enduring, trans-historical values. At the same time, its commitment to the idea of the individual artist of genius aligned it with the requirements of the art market. The central assumption shared by most practitioners was that art provided its beholders (or consumers) with a unique sensory experience unsullied by social or worldly concerns. One of the better examples of this kind of art history is Anthony Blunt’s book on Poussin (Blunt, 1966). This is a deeply scholarly monograph by the then director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, but it is a world away from current concerns in the discipline.

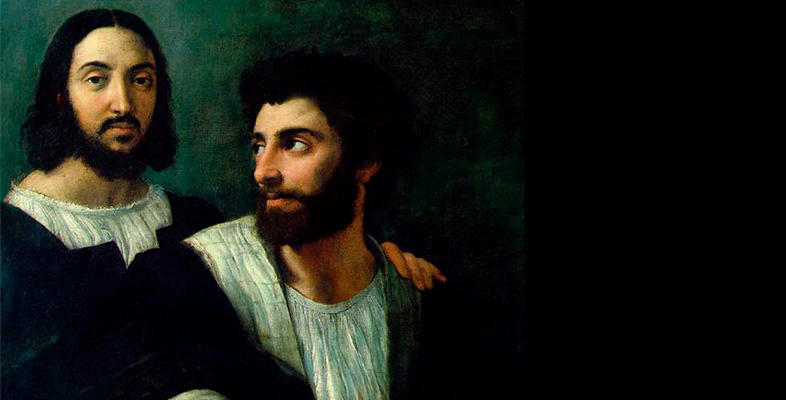

In 1973 Nicos Hadjinicolaou outlined what he saw as three blockages, or ‘obstacles’ to the production of a serious study of art in Art History and Class Struggle (Hadjinicolaou, 1978). The second obstruction was art history as a history of civilisations, and the third was art history as a history of works of art, but first in his list was art history as a history of artists. Hadjinicolaou’s work was one contribution to a transformation of the discipline in the 1970s and 1980s. During this time there was a growing feeling that art history could no longer be practised in the way that it had been. In the wake of the political upheavals of 1968, which had enormous reverberations in the universities, the sense of gentlemanly taste that underpinned the discipline seemed to many irrelevant if not downright reactionary.

What is sometimes called the ‘new art history’ or the ‘social history of art’ shook up the status quo by asking key questions about the foundations of art history. Drawing on ideas from Marxism, such as the concept of ideology, and subsequently from feminism, structuralism and psychoanalysis, art historians began to challenge the idea of art as an autonomous practice; that is, one separated from wider social forces and interests. New questions seemed to impose themselves:

- What ideological role did art play in sustaining established wealth and power, from the medieval church to the corporate museum?

- How did the institutions of art (the guild, academy, art school, auction house or gallery) shape its production and reception?

- Could art be used to challenge conservative ideologies?

- What role was available for women as makers or beholders of art?

- What place was there for art history as a critical discipline?

- What ideological assumptions were embedded in art history and its forms (the monographic book or exhibition, the catalogue, the survey course)?