2.1 Misconceptions and misreadings

The Art Historian John Shearman spent decades assembling a massive two-volume work, Raphael in Early Modern Sources (1483–1602) (Shearman, 2003). Shearman’s attention to documents and his frustration with overly simplistic readings of them underlines how scholars often fail to look critically at primary sources themselves, resulting in misconceptions or misreadings, which are passed on from generation to generation. However, is it possible to achieve an unbiased understanding of an authentic Raphael? Can the true ‘facts’ of Raphael’s life ever be extracted from the original documents, or purged of our own ‘mistakes’? The analysis of subjects and subjectivity teaches us that the artist’s work cannot exist for us outside the received image of his identity. Instead, by using Foucault’s terms, we might pursue Raphael’s author-function, that is the context surrounding its origin in early modern era, and its transformation through successive generations of critical reception.

Stephen Greenblatt’s new historicism and his writings on self-fashioning have been important for recent methods. Yet, some have been sceptical of Greenblatt’s emphasis on individual personalities who attempt to shape their own destinies, preferring to look instead at social networks, which operate collectively to negotiate identity, and at intersubjectivity. Raphael was not the only person interested in his creative persona. So too were his patrons and literary sponsors: we will see, for example, how his ally Baldassare Castiglione was an important agent in the shaping of Raphael’s identity. We will also see how the artistic persona ‘Raphael’ was formed by its opposition to that of ‘Michelangelo’.

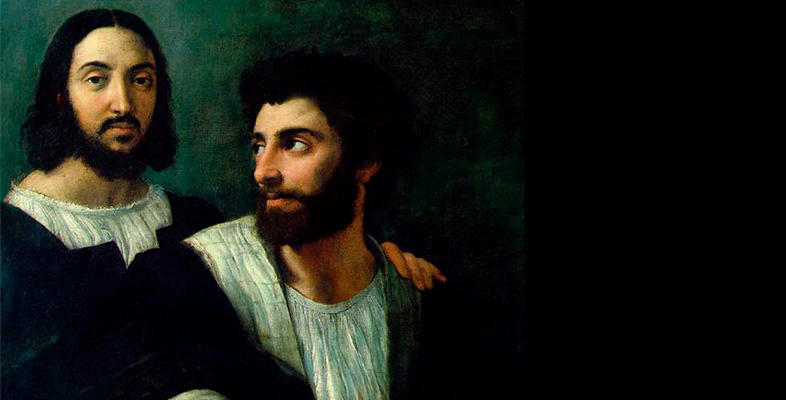

Looking at a Renaissance artist in detail is a particularly useful way of dislodging the sort of reverence for the individual, male genius that has been so dominant in art history. Yet how did Renaissance artists come to epitomise what it means to be an ‘artist’ in the European tradition? Here we will look back to the processes of invention that first created their cult of personality. Using texts and images we will assess how Raphael’s sixteenth-century biographies, portraits and his social behaviour at court shaped his (fictional) identity. A close reading of the sources allows us to consider how Raphael and his circle created ‘Raphael’, testing the boundaries between reality and invention. The point will be to access the creation of a major persona, one that defined a particular paradigm of artistic achievement – closely associated with grace, beauty and harmony – and an artistic ideal of classicism that endured for centuries.