2.10.2 Castiglione ‘paints’ Raphael

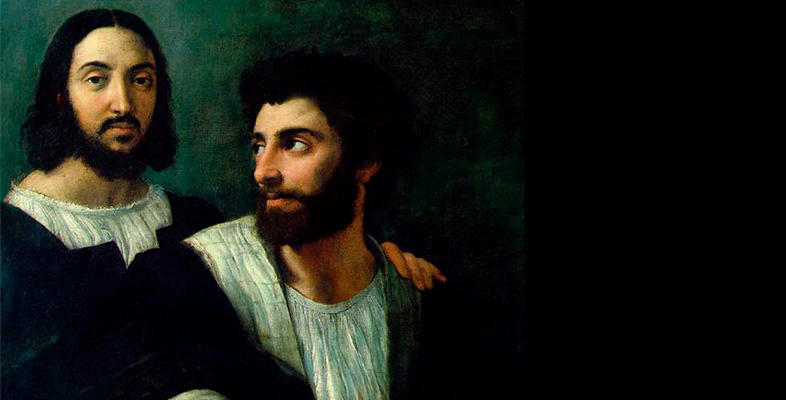

If Raphael has left behind the most lasting image of Castiglione, Castiglione was crucial in the formation of Raphael’s legacy, with vast implications for the artist’s posthumous reception.

Now consider two letters, one (probably) written by Raphael and the other (probably) written by Baldassare Castiglione in the voice of Raphael. The first is a transcription of a letter from the painter to his uncle reporting on recent events in Rome. Some doubts about its authenticity remain since the original document is now lost, but most scholars understand it to be genuine. Lodovico Dolce first published the second letter in 1554. This purports to have been written by Raphael and addressed to Castiglione. However, as Shearman first revealed, the second letter is a literary fiction written by Castiglione ‘in the guise’ of Raphael (Shearman, 1994). In it Castiglione pretends to be Raphael, using Raphael as a foil to present his own vision of a perfect artist.

Activity 5

Read the letters by Raphael [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] and by Castiglione in the voice of Raphael and consider the different personas that they channel.

- What sort of artist is Raphael when he writes to his uncle?

- What sort of artist is Raphael when Castiglione invents him in his literary portrait?

Discussion

In the first letter Raphael describes the wealth and prestige he has acquired as head architect of new St Peter’s, the site where the first pope, St Peter, was buried, and the holiest and most important church in Western Catholicism. He has a salaried position, which was rare at the time. The high sums Raphael brags about were, however, about to become extraordinarily controversial, since the vast amount of money used to re-build St Peter’s would become a core point of contention in the Protestant critique of the popes. These circumstances make the artist’s naiveté in touting his own sense of self-importance in this letter particularly striking.

The voice heard in the second letter could hardly be more different from that of the first. Here we find a highly sophisticated and erudite artist who expresses his own concepts of art in philosophical, Platonic terms. It is modelled precisely on the description of the sculptor Phidias in Cicero’s De Oratore: ‘while making the image of Jupiter or Minerva, Phidias did not look at any one model, but there settled in his mind a surpassing ideal of beauty ... so with our minds we conceive the ideal of perfect eloquence, but with our ears we catch only the copy’ (Shearman, 1994, p. 80). Emphasis is placed on the mind of the artist and the ideal images he is able to access, supposedly because of divine favour.

Castiglione’s letter has been highly influential in the reception of Raphael by generations of artists and scholars, since its status as a made-up image of an ideal Raphael was revealed only by Shearman’s article of 1994. Shearman judiciously analysed the letter’s language, content and context to show that it was composed after Raphael’s death, after an aura of divinity had already crystallised around him. A hint of Raphael’s Christ-like identity is seen, for example, in the reference to the ‘great weight’ that the Pope is said to have placed on his shoulders, which echoes the heavy cross carried by Christ up to the site of the crucifixion.