2.11.1 Raphael and Michelangelo

In the next exercise we look again at some primary and secondary sources about Raphael in order to examine the relation between Raphael’s persona and his style of painting.

Activity 6

- Thinking about the primary texts you read about Raphael’s death, Vasari’s Life of Raphael, and the biography of Raphael from the Oxford Companion, what are some of the connections made between the artist’s persona and his style of painting?

- Although we have not had the opportunity to consider the persona of Raphael’s rival Michelangelo here, if you have any familiarity with this artist you can also think about how Raphael’s artistic persona has been set apart from Michelangelo’s.

Discussion

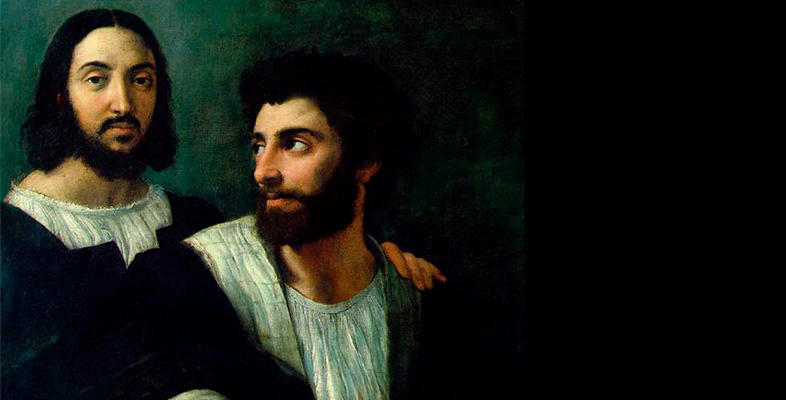

Raphael is divine and graceful; a work by Raphael is divine and graceful. ‘Raphael’ becomes less a biographical entity than an idea representing grace as the opposite of diligence, the epitome of polish that disguises any trace of the physicality involved in making a work of art. He represents the essence of aristocratic ease and grace. Celio Calcagnini called him the ‘prince of all painters’ (Letter from Celio Calcagnini in Rome to Jacob Ziegler [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ), while Vasari wrote in his biography of Raphael (‘Life of Raphael’) that as an infant he had drunk his own mother’s milk, not that of a nursemaid, thus avoiding ‘absorbing the manners of people of low condition’. This sets him apart from his greatest rival at the papal court, Michelangelo, whom Vasari tells us in his biography of the artist, was nursed by a stone-cutter’s daughter, from whom he drank in not only the art of sculpture but also the social coarseness that was thought to contribute to his difficult personality. Such direct contrasts are found everywhere in the biographies of these two colossal personalities, leaving long-lasting models of working practices and creative identities for generations to come.

Raphael always appeared elegant and Vasari writes that animals were naturally drawn to him, drawing a parallel between the artist and the gentle figure of St Francis or the musician Orpheus. Michelangelo, according to Vasari’s biography of him, cared nothing for his appearance and even slept in his boots. He worked largely alone without a workshop or assistants, disguised his own training and took on no pupils. Raphael’s artistic persona is closely associated with harmony, as is seen not only in the trope of the perfect unity of his workshop but also in the much-praised softness and delicacy of his technique, as well as his care at selecting a harmonious palette of colours.

Raphael’s art can be closely associated with an early modern notion of beauty as ‘a threefold grace which originates in harmonies: the harmony of virtues in souls, the harmony of colours and lines in bodies, and the harmony of tones in music’, which are all different forms of divine grace (Hendrix, 2010, p. 91). As a person of great beauty himself he seemed, much like his artistic creations, the best of humanity, an ideal that brings together, in one person, excellent traits normally found scattered in many different people. Raphael, the artist and the person, is a perfect and well-considered ‘composition’. Michelangelo, on the other hand, was thought to channel a different divinity, one charged with furia (demonic frenzy) and terribilità (terribleness), the uncontrolled forces of divine madness.

Raphael, in his own life and through his reception, has come to be identified as the paragon of the art of painting itself in its universality and its ability to blend, soften and unify. Michelangelo, by contrast, epitomises the art of sculpture in its gravity and the hard, unforgiving surface of marble. These are realities seen in their own work, tropes written into their biographies, and topoi of their art-historical identities.

Having read Foucault, it should be clear to you that these elements of the ‘author function’ of these two artists far exceed the reality of their lives. The invention of the two types in opposition to one another reveals the flaws of the monograph that treats a single life and work, a point that engages the possibility of intersubjectivity. If artistic personas are in and of themselves works of art, in the case of Raphael and Michelangelo they are pendant images that cannot be considered in isolation.