2.9 Raphael’s portrait

Self-portraiture is a fundamental element in the creation and reception of artistic personalities. It is a genre that first came into its own in the early modern era, and it is an essential part of any analysis of issues of subjectivity and self-representation. Self-portraits are different from other genres of image-making: consider, for example, that painters have to look in a mirror to study their own image and transfer it to the canvas or panel. The self-portrait thus somehow always embeds the process of representation itself, as an image that somehow ‘records’ the painter at work. Looking at a self-portrait, we see the artist looking at him or herself in a mirror, while at work.

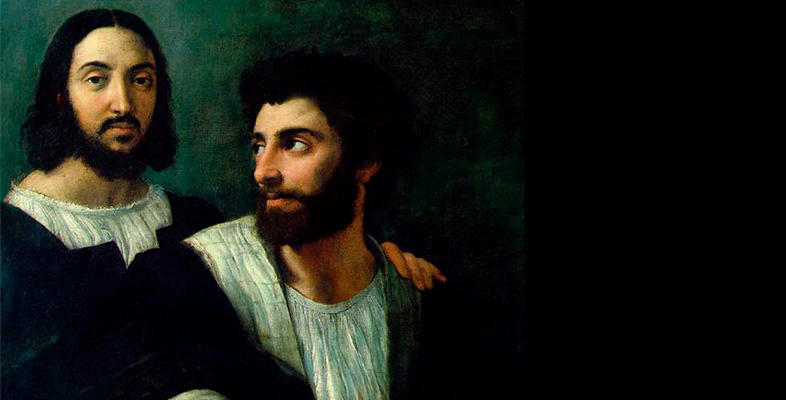

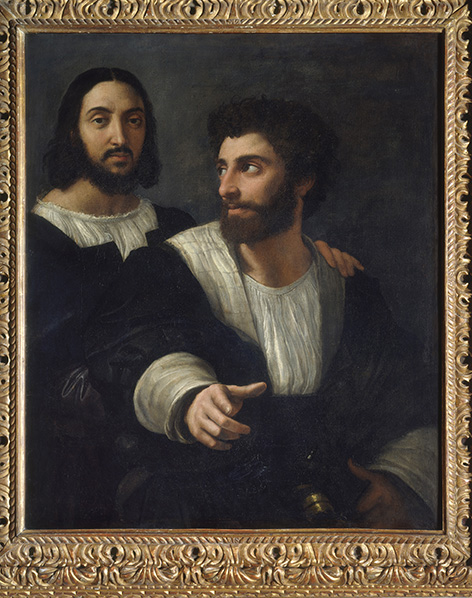

We will now consider an experimental double portrait by Raphael which uses the Holy Face as a model for self-portraiture: a double portrait he painted of himself and a companion, now in the Louvre (Figure 7).

Activity 3

Consider the self-portrait of Raphael (Figure 7). What does it reveal about the artist’s identity? What is the relationship between Raphael and the other sitter, and what does it seem to tell us about Raphael’s persona? Note that the second sitter’s identity is not known, despite much speculation by art historians.

Discussion

In this unusual composition, Raphael paints himself standing on the left, gazing out at the spectator, with his hand resting on the shoulder of his companion. This primary or dominant sitter is positioned underneath and in front of the artist. He looks backwards towards Raphael, pointing out of the canvas with his right hand, as if gesturing towards the viewer, and holding a sword in his left hand. Both men seem close in age and general appearance and their relationship is clearly one of friendship. Yet they are not equals: while Raphael is placed ‘above’ the other figure and seems slightly authoritative in the way he touches his shoulder, the second figure is dressed more expensively and the sword is a clear indication that he is not a fellow artist, but a person of higher rank.

Raphael is shown in a serene and serious pose. His elongated nose, parted, shoulder-length hair and beard, and his nearly front-facing pose all speak to conventions for the representation of Christ (see Figure 5). As the Lentulus letter reminds us, a connection was understood between Christ’s beautiful appearance and his innate goodness, associated in particular with youth, a sense of calm, sobriety and modesty. In the early modern era it was common to equate physical beauty with ‘goodness’, and to understand Christ as a paragon of both. The fifteenth-century Neoplatonic philosopher Marsilio Ficino, for example, wrote about the grace and inherent virtue of those who happen to resemble Christ in their appearance, since this is a sign of their souls’ affinity with the divine.

Unpacking the narrative and temporal moment shown in this portrait reveals further layers of complexity. Raphael looks at ‘us’ while the other sitter points to us and turns to Raphael, as if alerting the artist to the viewer’s arrival on the scene. This pointing hand and extended arm is itself a remarkable sign of the artist’s own ‘dexterity’, in particular his skills at representing the foreshortened human body, considered at the time to be a great artistic challenge.

Raphael’s direct, front-facing gaze reminds us that he is showing himself in the act of painting his own image – by necessity what he sees when looking into a mirror. Yet there is no sign on his face of the mental or physical strain that painting entails. Instead, his face is a vision of serenity, as if Raphael has translated his own mirrored image into the image of Christ when it was transferred – miraculously and without artistic intervention – onto Veronica’s veil.

The artist is poised and the aristocratic gentleman is wearing refined clothes. The sense of idealism is further suggested by the painting’s highly sophisticated compositional scheme: Raphael looks out of this picture, while his companion’s hand and extended arm brings both forward into the world outside. At the same time the companion’s glance brings us back into the picture and returns us to Raphael, as if to create a closed circuit that unites sitters and spectator.