Discovering Ancient Greek and Latin

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 23 April 2024, 7:23 PM

Discovering Ancient Greek and Latin

Introduction

Learn the basics of either Ancient Greek or Latin with this OpenLearn course.

Knowledge of classical Greek or Latin is essential for anyone wanting to get beneath the skin of the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome. This free course provides a taste of what learning Latin and Greek entails by taking you on the first steps of the journey towards learning these classical languages. It has been written with beginners in mind, especially those who have encountered the classical world through translations of Greek and Latin texts and wish to know more about the languages in which these works were composed. If you have looked at a classical text in the original language, you may recognise the gap that can exist between 1) possessing the ‘tools of the trade’ for reading ancient languages – such as a text, a dictionary, a commentary and a translation – and 2) actually being able to read the language! The aim of this material is to help you bridge this gap by introducing some of the linguistic skills required to navigate a passage of Latin, Ancient Greek or both.

Note that in this course all Greek is presented twice, first in Greek letters and secondly ‘transliterated’ into English letters. You can therefore study this material without knowledge of the Greek alphabet. You may, however, wish to acquire some knowledge of the alphabet and pronunciation before you begin, by looking at Introducing Ancient Greek.

If you are interested in the pronunciation of Latin, you may wish to look at Introducing Latin before you begin this course.

Note that references to the Greek language in this course are to Ancient Greek rather than modern.

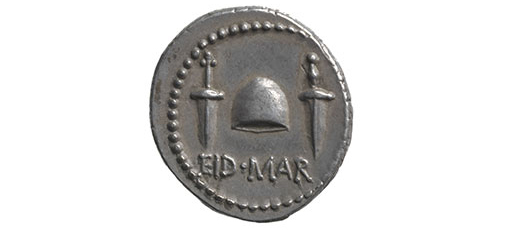

This is a colour image of one side of a coin shown against a white background.

The reverse shows two daggers. The one on the left has three globes on the pommel. The one on the right has one. Between the daggers is a cap.

Below these three objects is an inscription. It reads ‘EID MAR’.

An arc of raised dots runs around the coin. It is most prominent on the left where it is not so close to the edge of the coin.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A275 Reading Classical Greek: language and literature.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

explain why Greek and Latin are referred to as classical languages

understand some of the distinctive features of Greek and Latin and some features they share in common with other languages

understand why an English translation cannot represent a passage of Greek or Latin word for word

contrast the role of word order and word endings in Greek and Latin with those in English

explain the terms case, declension and (for Latin only) conjugation.

1 Characteristics of the Greek and Latin languages

If you embark on the study of Greek or Latin, what sort of language will you be learning? What are their distinctive features? What do they share in common with other languages?

We can start with one obvious characteristic. Both are referred to as ‘classical’ languages, a word which seems to endow them with a special status. But what does that really mean? There is no single or simple answer to this question. The attempt to answer it, however, can shed light on important features of both languages. It also leads directly to another central issue for any student of Greek and Latin. What can these languages offer us today and why do they continue to deserve further study?

Activity 1

What does the term ‘classical’ suggest to you? What do you think it means when applied to Ancient Greek and Latin?

Jot down your thoughts in the box below.

Discussion

Your answer will no doubt differ from the one below, but you might have noted that the word ‘classical’ can be used to describe some of the following:

- something old and traditional that has stood the test of time (and is, we might say, ‘timeless’)

- an artefact of great quality

- a thing that deserves to be copied or emulated

- something that sets the standard by which other things should be measured

- something old (and possibly out-of-date) in contrast to something new; for instance, ‘classical languages’ as opposed to ‘modern languages’, or ‘classical physics’ as opposed to ‘quantum physics’

- a particular style, embracing concepts such as balance, harmony, restraint and correctness. In this sense, ‘classical’ might be contrasted with the word ‘romantic’, denoting a more intuitive and free-spirited approach.

You might also have observed that the term is now applied very widely – to music, ballet, guitar, cuisine, economics, and so on. The range of applications can be extended even further by including the related word ‘classic’, as in ‘classic’ literature, films, cars and so on. Indeed to describe something as ‘classic’ sometimes amounts to little more than a vague statement of approval.

We shall look in more detail at the application of these terms to Latin and Greek at the end of this section. For the moment, note that each description in the list has at one time or other been applied to both Latin and Greek.

1.1 The spread of Greek

The origins of Greek are unknown and probably unknowable. The language is first found on Mycenaean clay tablets dating to around the middle of the second millenium BCE. This makes it the oldest attested European language still in use today. But its history as a language of literature begins not with the written word but with music and performance in the shape of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (eighth century BCE) and a great body of ‘lyric’ poetry performed at festivals and symposia (aristocratic drinking parties). At the same time it was also in daily use in Greek settlements across the Aegean sea, the coast of Turkey, Southern Italy, Sicily, North Africa and Asia Minor. But it was the great flowering of Greek literature in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE that established its prestige. This flowering took place chiefly in the theatres of Athens (in the work of the playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes), its agora (forum) and courtrooms (the orators Lysias and Demosthenes) and its philosophical schools (notably the Academy of Plato). We should also mention the Histories of Herodotus, Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War and its continuation by Xenophon in his Hellēnika (‘Greek events’).

The defeat of the Persian empire by Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) pushed what was still largely a coastal language further inland, notably in Egypt, the Middle East and Turkey. Crucially for the development of the Greek language, these events also led to the establishment of numerous Greek cities, the most important being Alexandria at the mouth of the river Nile (331 BCE). It was here rather than in mainland Greece that the greatest library of Greek literature was established. Subsequently a more standardised form of Greek developed to take the place of the variety of dialects that had existed to this point. This ‘common dialect’ (koinē dialektos), was heavily influenced by the literature of Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, making it accessible to a modern reader with some experience of authors from this period, such as the orator Lysias or the philosopher Plato. The most influential works written in koinē Greek are the 27 books of the New Testament.

This is a horizontal, rectangular map in colour. An area of enclosed sea is shown in blue surrounded by land in green. The sea occupies the left-hand side of the map. No compass or scale is provided.

The legend indicates that red areas are core areas of literary culture. White areas show the general spread of literary culture. The date 350 – 1 bce can be seen in the bottom left-hand corner beneath the legend.

The core areas of red centre on the wide irregularly-shaped peninsular where Athens is located. It reaches up as far as Pella. Across the sea to the left, strips of red are shown along the lower edges of a boot-shaped section of land. It spreads in a narrow strip to the island where Syracuse is located below the toe of the boot. It does not reach up as far as Rome.

A wide coastal strip opposite the irregular peninsular to the right where Pergamon is located is also shown in red as is the pan-shaped island below it further right. On the coast below the island at the bottom of the map a small strip of land that follows the course of a river between Alexandria and Oxyrhynchus is also shown in red.

The general spread of literary culture is shown in white. All of the areas on the edge of the red sections are shown in white. Some are narrow strips but the area to the right beyond Pergamon is much wider. Below it on the right-hand coast opposite the red pan-handle island it extends from Antioch to almost the right-hand edge of the map. This large area is linked by a white coastal strip to the area below it between Alexandria and Oxyrhynchus.

No red or white areas are visible on the left from here to Carthage although there is a small pocket of white between them around Cyrene. This pocket is on the coast opposite the irregular peninsular where Athens is located.

1.2 The spread of Latin

One clue about early Latin exists in the name. Why ‘Latin’ and not ‘Roman’? The answer to that question is in the beginnings of Rome itself. Latin was originally the language not of Rome but of Latium, a small region south-east of the river Tiber inhabited by the ‘Latini’, now part of the much larger Italian region of Lazio. Rome was, at first, just one of a number of cities in this area, although by 300 BCE she was the dominant one and the conquest of Latium was complete.

In one respect the history of Latin is the opposite of Greek. Greek already had an impressive literary pedigree before being carried further afield by the imperial conquests of Alexander the Great. For Rome, on the other hand, empire came first. Latin literature appears from around the middle of the third century BCE, by which time Rome was the strongest power in Italy and was beginning to create provinces overseas in Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia. More than two centuries later in the time of Virgil, Horace and Livy, Rome could already boast a long history as an imperial power, and its empire included provinces carved out of the kingdoms ruled by Alexander the Great’s successors in Greece and Syria, along with the recently added kingdom of the Ptolemies in Egypt. The development of Latin, especially Latin literature, needs to be seen against this background. It can be understood in part as the conscious creation of a language and literature to match Rome’s imperial achievements and a language appropriate for telling Rome’s story.

1.3 Family resemblances

Let us now take a closer look at the languages themselves.

Neither language is unusual from a strictly linguistic point of view. It is easier to trace connections between them and other languages than to identify any unique characteristics. You can appreciate this by thinking in terms of a ‘family tree’ of languages, with younger languages inheriting characteristics from older ones. This so-called ‘genetic’ approach to language classification gathered momentum in the late eighteenth century, especially after the demonstration in 1786 that Greek and Latin shared roots with Sanskrit, the ancient language of India. The excitement generated by this discovery is neatly captured in the following contemporary account:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of the verbs and in the forms of the grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer [i.e. linguist] could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.

1.4 Indo-European

The discovery of connections with Sanskrit made it possible to place Greek and Latin within a larger group known today as the ‘Indo-European’ family of languages. This family embraces almost all of Europe, Iran and Northern India. All of these speakers use languages descended from a common ancestor known as ‘Proto-Indo-European’ which, though lost, can be reconstructed to a certain extent. These shared origins across Indo-European languages are particularly clear in similarities of vocabulary, notably in words denoting family relationships.

| Language | Word for ‘father’ |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | piter |

| Greek | patēr |

| Latin | pater |

| Irish Gaelic | athair |

| German | Vater |

| English | father |

Although the Indo-European family contains a relatively small number of languages (around 100; there are an estimated 6000 languages in use in the world today), it contains a larger number of native speakers than any other family. One estimate puts the number of people whose native language is Indo-European at roughly 1.7 billion.

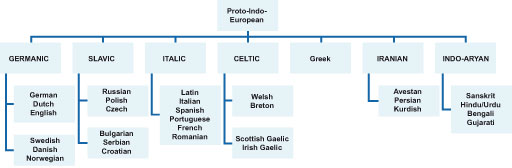

This is a tree diagram with linking lines in dark blue and blocks containing languages in light blue.

At the top there is a dark blue horizontal line with seven short vertical branches. These are all linked in the centre to ‘Proto-Indo-European’ which is shown in the light blue block above it.

The seven branches from left to right are ‘GERMANIC’, ‘SLAVIC’, ’ITALIC’, ‘CELTIC’, ‘Greek’, ‘IRANIAN’ and ‘INDO-ARYAN’. Of these only Greek has no links further down the tree.

To the far left is GERMANIC. Two branches are connected to it. In the upper block is ‘German’, ‘Dutch’ and ‘English’. In the lower block is ‘Swedish’, ‘Danish’ and ‘Norwegian’.

Further to the right is ‘SLAVIC’. Two branches are connected to it. In the upper block is ‘Russian’, ‘Polish’ and ‘Czech’. In the lower block is ‘Bulgarian’, ‘Serbian’ and ‘Croatian’.

Further to the right is ‘ITALIC’. One branch is connected to it. In this block is ‘Latin’, ‘Italian’, ‘Spanish’, ‘Portuguese’, ‘French’ and ‘Romanian’.

In the centre is ‘CELTIC’. Two branches are connected to it. In the upper block is ‘Welsh’ and ‘Breton’. In the lower block is ‘Scottish Gaelic’ and ‘Irish Gaelic’.

To the right of this is ‘Greek’. There are no connecting branches.

Further to the right is ‘IRANIAN’. One branch is connected to it. In this block is ‘Avestan’, ‘Persian’ and ‘Kurdish’.

To the far right is ‘INDO-ARYAN’. One branch is connected to it. In this block is ‘Sanskrit’, ‘Hindu/Urdu’, ‘Bengali’ and ‘Gujarati’.

All the languages in the light blue blocks stem from ‘Proto-Indo-European’.

1.5 Word endings and word order

In addition to locating languages ‘genetically’ on a family tree, we can classify them ‘typologically’, on the basis of shared linguistic features – for example according to patterns in the way they use sounds, word endings or grammar. From this perspective too there is nothing special about Greek and Latin. Although both contain features unfamiliar to English speakers these can easily be paralleled elsewhere. Note, for instance, the following two points which set them apart from English (and which we will inspect in more detail later).

Word endings

Greek and Latin use a rich system of word endings to convey information such as the tense of a verb, the relationship between an adjective and the noun it describes, or the role of a noun within a sentence. This approach to conveying information would be recognisable to speakers of German, Russian, Finnish, or indeed any of a large group of ‘inflected’ languages, ‘inflection’ being the name given to a change in the shape of a word. English itself was originally more inflected than it is today, and still retains some examples, as we shall see later.

Word order

Where English says ‘Brutus murdered Caesar’, Greek and Latin prefer the word order ‘Brutus Caesar murdered’. Indeed they have the option of placing the words in any order without altering the meaning of the sentence. Again, we will leave the details for later. For the moment, notice again that this preference for placing the verb at the end, though different from English, can be found in other languages (like Turkish) as can the greater flexibility in word order.

1.6 Language and literature

In addition to looking at the mechanics of languages, it is also important to consider the way they were actually used. One fact of great importance for the development of Greek and Latin is that they became vehicles for writing literature (which is not true of every language). This pushed them in novel and interesting directions, allowing them to express new ideas with freshly minted words or with existing words endowed with new meanings.

We catch sight of this process in the development of Latin as a philosophical language. The responsibility for this lies primarily with Cicero, who has been credited with creating ‘nothing less than a whole language and literature of Latin philosophy’ (Taplin, (2001) Literature in the Roman World, Oxford, Oxford University Press, p. 41). This ‘philosophical’ language included works such as ‘On The Republic’ (De re publica) and ‘On Laws’ (De legibus), inspired by Plato’s similarly named Republic and Laws, along with a great deal of new technical vocabulary for expressing philosophical ideas which until that point could only be expressed satisfactorily in Greek. Much of this work took place in a short burst of productivity during the years 45 and 44 BCE. We can only speculate what Cicero might have achieved, and its impact upon Latin, had he not been killed in 43 BCE on the instructions of Mark Antony. Here are some words coined by Cicero, with Greek equivalents where they exist.

| Latin | Greek | |

|---|---|---|

| quālitās | ποιότης (poiotēs) | quality, distinguishing characteristic |

| mōrālis | ἠθικός (ēthikos) | concerned with ethics, moral |

| essentia | οὐσία (ousia) | essence |

| hūmānitās | human nature |

The Greek words had in their turn been invented centuries earlier for the purpose of philosophising. Indeed Plato, who coined the word ποιότης (poiotēs) for ‘quality’ (from ποῖος, poios, meaning ‘of what kind?’), apologised to his audience for its strangeness (Theaetetus, 182a).

If we wish to emphasise the expressive power of Greek and Latin, we need to think of this not as a built-in feature of either language, but as the result of a long process of development, stimulated by a number of factors which include:

- the ambition, imagination and sheer hard work of individual authors

- competition between writers, sometimes literal as in the dramatic contests in Athens and other Greek cities

- the existence of a rich and varied literary tradition for inspiration. For Romans, this tradition was Greek as much as Latin

- a supportive environment for writing – such as the cycle of festivals in classical Greece, the ‘bookish’ culture of the library of Alexandria, a circle of like-minded aristocratic friends and readers in first century BCE Rome, or the patronage and encouragement of writers under the Emperor Augustus

- the role of both languages within long-lived historical institutions, such as the Empires of Alexander the Great and his successors, the Roman Empire and the Christian Church.

1.7 The quantity of Greek and Latin

It seems odd to consider the quantity of writing rather than its quality. Nevertheless, the sheer volume of classical writing, especially in Greek, is remarkable and forms an important backdrop against which to consider any individual author or work of classical literature. Most of this writing has been lost but we catch occasional glimpses of how much must have once existed. The library of Alexandria, for instance, is said to have contained half a million rolls of papyrus; its nearest rival, the library at Pergamum near Troy contained some 200,000.

This is a colour photograph of the elaborate front of a partially restored two-storey building seen from the left against a blue sky. It is built of stone in the Classical style. It is set on a raised platform accessed by nine steps which rise from a courtyard. The steps run across the full width of the building and are bounded at either end by a short wall. They lead to a two-storey galleried porch.

At the front of the lower storey there are eight smooth one-piece columns, three of which have been heavily restored. The column bases are set on square plinths with concave sides and are of uneven height. Their capitals are a mixture of Ionic spiral volutes set above Corinthian acanthus leaves. The columns are arranged in four pairs each supporting an entablature. They are unevenly spaced with the distance between the two central pairs being wider than the rest, so that it frames the wide central door which can be seen beyond them.

Above these, on the upper storey are a further eight smooth thinner columns with their bases set on large rectangular plinths which are supported by the four entablatures below. Two columns share each of the four plinths. The columns have Corinthian acanthus leaf capitals. The central six columns are arranged into three pairs adding height to those beneath. The spacing between the central pair mirrors the wider space below. The columns at either end stand alone with a stone lintel joining their tops to the back wall. The upper three pairs of columns are capped by entablatures, each supporting partially restored decorated pediments. The central one is triangular and those either side of it are curved.

Beyond the columns of the galleries is the outer full height front wall of the building.

On the lower floor there are three entrances in the wall with windows above them. The central entrance is wider and taller than the other two. The window above it is correspondingly shorter. Four decorated rectangular niches are arranged on either side of the doorways. Clothed statues stand on short inscribed pedestals within the recesses. The two on the right are headless. The unrestored stone and bricks of the interior walls of the building are visible through the doorways and windows. They are not visible beyond the first storey.

Three windows can be seen on the second storey in line with those above the lower doorways. They are framed by the three thinner pairs of columns. Four tall empty plinths are set on the upper storey above the position of the niches below.

The building lies tightly between two others which run perpendicular to it. The front of the one on the right has an arched entrance which can just be seen and has been restored to the height of the first storey, whereas the building on the left is in ruins. Further ruins can be seen in the immediate foreground.

The shared courtyard in front of the buildings is covered by modern material. A section of the original paving is exposed on the far right.

It is worth keeping this larger context in mind when researching a particular author. A useful question to begin with is what did he (or, rarely, she) write and how much has survived? The answer might be sobering. Try the following question.

Activity 2

a.

roughly 100

b.

roughly 200

c.

roughly 300

The correct answer is c.

Answer

Our best estimate is around 300. Although most of the plays do not survive, lists of titles are preserved from the Byzantine era.

Euripides seems more prolific than his rivals, but the figures are misleading. We possess more of his works thanks to the chance survival of a volume of plays beginning with Greek letters from epsilon (the fifth letter of the alphabet) to kappa (the tenth).

Similar misfortunes have befallen Latin authors. Of the 142 books of Livy’s history of Rome, only books 1−10 and 21−45 survive, with a few gaps. Likewise there are gaps in the works of the historian Tacitus, perhaps most frustratingly for historians his account in the Annals of the death of the emperor Tiberius, the reign of Gaius (Caligula) and the accession of Claudius.

Another important question is how much literary work was taking place outside the canon of well-known authors. Comedy provides an interesting comparison with tragedy here. The only complete comedies to survive from the fifth century BCE are those written by the comic playwright Aristophanes (eleven of whose plays survive in total, representing around 25 per cent of his total output). But as with tragedy, we know the names of many more comic playwrights whose works are either lost or survive only in fragmentary form.

Activity 3

How many comic poets do you think were writing in the fifth century BCE? What kind of scholarly tools might you use to help you arrive at an informed estimate?

Discussion

Although we cannot hope to answer this question precisely, there are various resources we can use to help us to arrive at an estimate. An obvious place to start might be a reference work like the Oxford Classical Dictionary whose entry on ‘comedy (Greek), Old’ provides some basic information on early comedy (‘Old Comedy’ is the name given to the kind of comedy being written in the fifth century BCE, which differs from later ‘Middle Comedy’ and ‘New Comedy’). This OCD entry contains the names of some of the better known fifth-century playwrights, and also points you towards further reading, such as modern collections of surviving fragments of comic writers.

Another approach is to use an online resource such as the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (‘Treasure Store of the Greek Language’, usually abbreviated to TLG), a database which contains a list of ancient authors tagged by genre (e.g. ‘comic.’, ‘epic.’, ‘hist.’, ‘trag.’). The basic TLG (which is free to use) is hugely useful for students and scholars alike, but since it contains only surviving, canonical works, it is hardly surprising that a search of this database reveals the name of just one fifth-century BCE comic writer: Aristophanes. But our search of the full database produced 49 results, giving a rough indication of the amount of non-Aristophanic comedy written in the fifth century BCE.

1.8 ‘Classical’ languages

We can return now to the term ‘classical’. As you study the classical world, you might like to reflect on the usefulness or otherwise of the term. Here are a few observations, although the list is by no means exhaustive or immune to challenge. The main thing is to treat the word ‘classical’ carefully and critically, and to be aware that it can rule out as much as it rules in.

Here are a few potential weaknesses with the term:

- It can be used both to describe historical periods and to evaluate them (usually favourably). We might compare a term like ‘1960s’, which is sometimes used in the same way, although in this case the evaluation is often unfavourable.

- It has both a narrow and a broad sense. It can be applied narrowly to ‘classical’ periods within Greek and Roman history (fifth- and fourth-century-BCE Athens, and Rome of the first centuries BCE and CE), and, more loosely, to the Ancient Greek and Roman worlds as a whole.

- Some fundamental works of Greek and Latin fall outside the narrow definition, including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (eighth century BCE) and St. Jerome’s Latin translation of the Bible, the so-called Vulgate, from the fourth century CE.

- It views the classical world through its art, above all its great literature. It may therefore divert attention from other traces of the ancient world such as coins, inscriptions, papyri, and, above all, the physical remains studied by archaeology.

- It emphasises the extraordinary over the ordinary. One could argue that ‘ordinary’ writing tells us as much about a society as ‘extraordinary’ literature. We must at least acknowledge that both emerge from the same society.

- Tastes change and the idea of what is ‘classical’ can change with them. The first-century-CE Roman poet Statius, for instance, is today known only to specialists, but his epic poem on the legend of Thebes (Thebaid) was profoundly influential in the medieval period, and he was read by both Dante and Chaucer (who refers to him as ‘Stace’).

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that the term has a number of strengths:

- It expresses the influence of both languages on European culture.

- It is a historically important concept, central to the survival of interest in Greece and Rome, even if its influence is weaker today than in the past.

- It highlights one central reason for studying classics – direct access to important works of literature.

- The Greeks and Roman themselves thought in terms of ‘classical’ periods, i.e. periods where literature and art were believed to be authoritative and worth emulating. ‘Classical’ is itself a Latin term, from the Latin word ‘classicus’ meaning of the highest class.

- It captures the close relationship between Greek and Roman culture. It is useful to have a single word to make this point. ‘Greco-Roman’ is a more neutral term for expressing the same idea.

2 Beginning Latin

Your first encounter with a classical text is likely to take place through an English translation. To delve deeper, the next step might be to acquire the Latin text and a Latin–English dictionary. With these in hand you can inspect the text and translation in parallel, trying to relate one to the other.

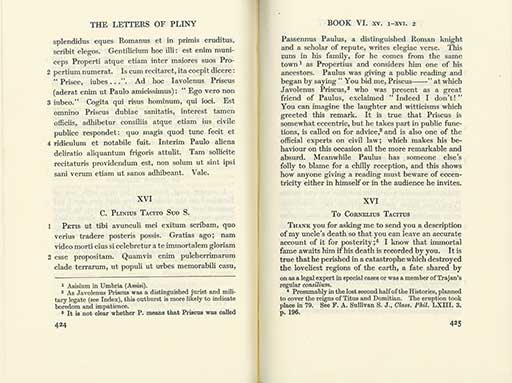

This is a colour image of an open book with cream pages. The page numbers are 424 on the left and 425 on the right.

The title at the top of the left-hand page is THE LETTERS OF PLINY. Below it are fourteen lines of Latin text. The line numbers 2, 3 and 4 appear at intervals down the left. Beneath this text is a central heading XVI followed by a longer heading and five lines of Latin text. The line numbers 1 and 2 appear against two of the lines. Beneath this section is a horizontal line with five lines of footnotes underneath.

The title at the top of the right-hand page is BOOK VI. xv. 1-XVI. 2 followed by eighteen lines of English text. Beneath these is the central title XVI with the heading ‘To Cornelius Tacitus’ below it. This is followed by a further thirteen lines of English text.

You can make some headway with this approach. It has the great advantage of allowing you to work with ‘real’ Latin composed by a native Latin speaker. Eventually, however, its limitations will become clear. Two problems stand out in particular:

- An English translation typically contains more words than its Latin equivalent. From the standpoint of English, some words appear to be ‘missing’ in Latin.

- English word order will almost certainly differ from the Latin.

These problems arise because English and Latin work on different principles. If you can grasp these principles and their implications, you will have taken an important step on the path to reading Latin as Latin instead of through the medium of English.

In the following sections, you will work step by step through some short pieces of Latin, including two small extracts from the works of the Roman aristocrat Pliny the Younger and the poet Catullus to see how these differences work in practice.

2.1 Parallel text 1: Pliny

Here is a short extract from Pliny in English and Latin, together with notes on individual words and phrases. Spend a couple of minutes familiarising yourself with it and seeing how much, if any, you can understand. Then attempt the questions that follow with the aid of the translation and the dictionary entries provided in Table 3.

Pliny the Younger, Letters, 6.16.1.

In this extract, Pliny begins his response to a request from the historian Tacitus for information about the death of his uncle after the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE.

English

You ask that I describe to you the death of my uncle, so that you can transmit it more truthfully to future generations.

Latin

petis ut tibi auunculī meī exitum scrībam, quō uērius trādere posterīs possis.

A note on long vowels

Long vowels in Latin have been marked with a horizontal line above the letter, called a ‘macron’ (from the Greek word for ‘long’). Thus the ‘i’ in scrībam is pronounced like the vowels in the English word ‘meet’ rather than ‘sit’.

A macron is an aid to pronunciation. In some situations, an understanding of pronunciation can help you understand the full meaning of a Latin word. The ‘Introducing Latin’ site contains more information on the pronunciation of Latin.

| Latin | English | Dictionary entry |

|---|---|---|

| petis | you ask | petō – ‘I seek, ask’ |

| ut | that | ut – with requests, meaning ‘that’ |

| tibi | to you | tu – ‘you’ (singular) |

| auunculī | of (my) uncle | auunculus – ‘uncle’ |

| meī | my | meus – ‘my’ |

| exitum | death | exitus – literally ‘departure’, here meaning ‘death’ |

| scribam | I describe | scrībō – ‘I write’ |

| quō | so that | quō – ‘so that’ (literally, ‘by which’) |

| uērius | more truthfully | uērus – ‘true’ |

| trādere | transmit | trādō – ‘hand over’, ‘transmit’ |

| posterīs | to future generations | posterī – literally ‘those who come later’, i.e. ‘future generations’ |

| possis | you can | possum – ‘I can’ |

Activity 4

Jot down the Latin equivalent for the following:

- You ask

- the death of my uncle

- transmit

- to future generations

Answer

| English | Latin equivalent |

|---|---|

| You ask | petis |

| the death of my uncle | auunculī meī exitum |

| transmit | trādere |

| to future generations | posterīs |

Activity 5

What do you notice about the ratio of Latin words to English in this passage?

Discussion

The English translation uses almost twice as many words as Latin (23 English words to Latin’s 12). Most Latin words in this extract are represented by at least two English ones.

Of course a different English version might have deployed fewer words (or perhaps more). The chosen example is not, however, especially wordy or untypical. It would certainly be impossible to produce anything like a literal English translation in just 12 words.

2.2 Parallel text 2: Catullus

Now look at the opening lines of Catullus and the dictionary entries in Table 4 below.

Catullus, Poems, 1.1−2.

Catullus introduces his book of poetry.

English

To whom do I give my charming, new booklet

recently polished with dry pumice?

Latin

cui dōnō lepidum nouum libellum

āridā modo pūmice expolītum?

| Latin | English | Dictionary entry |

|---|---|---|

| cui | to whom? | quis? – ‘who?’ |

| dōnō | do I give | dōnō – ‘I give’, ‘I present’ |

| lepidum | my charming | lepidus – ‘pleasant’, ‘charming’, ‘elegant’ |

| nouum | new | novus – ‘new’, ‘novel’ |

| libellum | booklet | libellus – ‘little book’, ‘booklet’ |

| āridā | dry | āridus – ‘dry’ |

| modo | recently | modo – ‘recently’ |

| pūmice | with pumice | pūmex – ‘pumice-stone’ |

| expolītum | polished | expoliō – ‘polish’ |

Activity 6

Jot down the Latin equivalent for the following:

- To whom do I give

- booklet

- with dry pumice

Answer

| English | Latin equivalent |

|---|---|

| To whom do I give | cui dōnō |

| booklet | libellum |

| with dry pumice | āridā pūmice |

Activity 7

a.

It supports it

b.

It contradicts it

c.

It has no bearing one way or the other

The correct answer is a.

Discussion

The passage of Catullus supports this idea, with 14 English words being used to represent 9 Latin ones.

2.3 ‘Missing’ words

Counting words is a rather simplistic way to analyse the difference between Latin and English. Nevertheless, it demonstrates one reason why it is impossible to relate English to Latin on a word-for-word basis. Some words in English have no direct equivalent in Latin. Where, then, are the ‘missing’ words?

There are some words which Latin cheerfully lives without. The lack of indefinite and definite articles (‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’) is perhaps surprising for English speakers. Latin has no direct equivalents, in spite of the fact that the Latin words unus (‘one’) and ille (‘that’) are ancestors of the indefinite and definite article in Romance languages (such as ‘un’, ‘una’ and ‘el’, ‘la’ in Spanish).

However, the ‘missing’ words of most interest here are those which reveal something about the way Latin works. Look again at the translations. The words in bold have no direct equivalents in Latin but are instead represented by the endings of words. We will see how this works in detail in the following pages.

Pliny the Younger, Letters, 6.16.1.

English

You ask that I describe to you the death of my uncle, so that you can transmit it more truthfully to future generations.

Latin

petis ut tibi auunculī meī exitum scrībam, quō uērius trādere posterīs possis.

Catullus, Poems, 1.1-2.

Catullus introduces his poems.

English

To whom do I give my charming, new booklet

recently polished with dry pumice?

Latin

cui dōnō lepidum nouum libellum

āridā modo pūmice expolītum?

2.4 Word endings

You might have noticed already that some Latin words used in the passages of Pliny and Catullus differ slightly from their dictionary entries. This is a sure sign that changes in the form of words play a role in the Latin language. Look, for instance, at the word for ‘uncle’. Compare the word as it appears in the text (auunculī) with its dictionary entry (auunculus) in Table 5. They differ by one letter at the end, which makes a crucial difference to the meaning of the word.

| Latin | English | Dictionary entry |

|---|---|---|

| auunculī | of (my) uncle | auunculus – ‘uncle’ |

Activity 8

a.

Fewer than half

b.

More than half

The correct answer is b.

Answer

More than half of the words are used by Pliny in a different form from their dictionary entry. They are listed below.

| Latin | English | Dictionary entry |

|---|---|---|

| petis | you ask | petō – ‘I seek, ask’ |

| tibi | to you | tu – ‘you’ (singular) |

| auunculī | of (my) uncle | auunculus – ‘uncle’ |

| meī | my | meus – ‘my’ |

| exitum | death | exitus – literally ‘departure’, here meaning ‘death’ |

| scrībam | I describe | scrībō – ‘I write’ |

| uērius | more truthfully | uērus – ‘true’ |

| trādere | transmit | trādō – ‘hand over’, ‘transmit’ |

| posterīs | to future generations | posterī – literally ‘those who come later’, i.e. ‘future generations’ |

| possis | you can | possum – ‘I can’ |

Your results could differ from these if you have used your own dictionary. Some dictionaries will contain entries for certain forms like tibi, although this would refer back to the entry for tu.

Now try the same activity with the English translation.

Activity 9

a.

Fewer than half.

b.

More than half.

The correct answer is a.

Answer

Very few and, certainly, less than half. The precise number may differ depending on the dictionary you use. ‘Generations’ will appear under ‘generation’; ‘truthfully’ might appear under ‘truthful’.

Activity 10

What problem would arise with a dictionary containing an entry for the word ‘generations’?

Discussion

A dictionary containing ‘generations’ would need to include every plural noun, such as ‘cats’, ‘dogs’, ‘bicycles’, and so on.

When learning English, it would be a pointless to learn all the forms of nouns that have plurals ending with ‘-s’. Instead, it is more sensible to learn a rule: that regular English nouns in the plural follow a pattern of adding ‘-s’ (or ‘-es’ if the noun ends in -ch, -sh, -s, -x or -z). There are exceptions like ‘mouse / mice’ and ‘goose / geese’ which must be learned individually and may well have their own entries in an English dictionary. But the majority follow a pattern that English speakers need to learn.

2.5 Word order

You have seen the first difficulty in relying entirely upon a translation and a dictionary. Some English words are not represented by Latin words at all. Now let us consider a second problem.

Activity 11

Look again at the verbs highlighted in Pliny’s letter to Tacitus. What do you observe about the position of verbs in Latin compared with English.

petis ut tibi auunculī meī exitum scrībam, quō uērius trādere posterīs possis.

You ask that I describe to you the death of my uncle, so that you can transmit it more truthfully to future generations.

Discussion

The verb ‘ask’ (petis) in Latin appears at the start of the sentence, as in English. By contrast, the verbs ‘write’ (scrībam) and ‘can’ (possis) are delayed until end of their respective clauses. The placement of a verb at the end of its clause is typical of Latin, which can be classified as a ‘Subject – Object – Verb’ language, or ‘SOV’ language for short.

Activity 12

Examine the phrase āridā modo pūmice expolītum in Catullus. What would an English translation with the same word order look like? What would be wrong with such a translation?

Discussion

The English would be ‘with dry recently pumice polished’. This is so odd that it is difficult to make a sensible comment about it! It certainly does not qualify as a translation or even as a piece of English.

Nevertheless, we can make one useful observation. In English, related words are usually close to each other, giving two natural ‘chunks’, ‘recently polished’ and ‘with dry pumice’. In Latin, by contrast, these chunks can be broken up.

ĀRIDĀ modo PŪMICE expolītum

2.6 Recap

You cannot map an English translation word for word onto its Latin equivalent for two main reasons:

- English tends to use more words than Latin, especially little words such as pronouns (‘I’, ‘you’) and prepositions (‘of’, ‘to’).

- Latin word order is more free than English and usually different.

Activity 13

a.

a. The English word might be in a different position.

b.

b. The English word might not be represented by a Latin word at all.

c.

c. Both a. and b.

d.

d. Neither a. nor b.

The correct answer is c.

For English speakers, coming to grips with word endings is usually the main challenge in learning Latin. It involves not only knowing the endings, but, more importantly, understanding their uses and their implications for the meaning of a sentence. We shall explore this in more detail in the next two sections. In the process, you may find yourself acquiring insights into the workings of English as well as Latin. And if you can overcome the thought that Latin is a language of missing words and a strange word order, then you are well on your way to thinking in Latin rather than in English.

3 Latin noun endings

Latin has six cases, each with its own ending and functions. In this section we will look at three of these: the genitive, dative and ablative.

3.1 ‘Of’ and the genitive case

When Pliny mentions ‘the death of my uncle’ he uses the phrase auunculī meī exitum. Uncle is auunculus, but the change of ending from ‘-us’ to ‘-ī’ signals a relationship between the noun ‘uncle’ and the noun ‘death’ (exitum). In English this relationship is expressed by the preposition ‘of’ (‘the death of my uncle’).

English can also express the same idea with a change of word ending, as in ‘my uncle’s death’, with an apostrophe followed by the letter ‘s’. This is a rare instance of English working like Latin by deploying a noun ending.

Examples

- carmina Catullī – the poems of Catullus

- dīvī fīlius – son of a god (one of the titles of the Emperor Augustus, a reference to his adoptive father Julius Caesar)

- altae moenia Rōmae – the walls [moenia] of lofty Rome

- amīcī Cicerōnis – friends of Cicero

- Iēsus Nazerēnus Rēx Iūdaeōrum – Jesus from Nazareth, King of the Jews

The genitive case

These endings are examples of the ‘genitive’ case in Latin. You can think of the genitive case as the ‘of’ case. It generally links two nouns (as in carmina Catullī).

Caution

English uses ‘of’ in a wider range of situations than Latin

- I speak of many things

Note that ‘of’ here does not express a relationship between two nouns. It is closely related to the verb ‘speak’ and is equivalent in meaning to ‘about’.

Practice

Activity 14: the genitive case

Select the Latin nouns in the genitive case.

a.

Rōma

b.

caput

c.

mundī

The correct answer is c.

a.

Caesaris

b.

uxor

The correct answer is a.

a.

Turnus

b.

rēx

c.

Rutulōrum

The correct answer is c.

3.2 ‘To’, ‘for’ and the dative case

When Pliny wants to say ‘to you’, he takes the word ‘you’ (tu) and uses the form tibi. To say ‘for future generations’ he changes the ending of the word posterī (literally ‘those who come afterwards’) and writes posterīs. These endings are examples of the dative case, which in English would typically be expressed by the prepositions ‘to’ or ‘for’.

The dative case often involves the idea of someone giving or transmitting something to someone. (The word ‘dative’ derives from the Latin verb dō, ‘I give’). Note that English can say both ‘I gave a book to him’ or ‘I gave him a book’. In both examples, Latin would typically use a dative case.

Examples

- scrībō tibi – I write to you

- grātiās agimus Augustō – we give thanks to Augustus

- sōl omnibus lucet – the sun shines for everyone (or ‘upon’) everyone

- cui dōnō ...? – To whom do I give

Catullus begins his collection of poems with a dative case (cui? – ‘to whom?’), appropriately so in a poem whose topic is a dedication. He answers his own question in the third line with another dative, referring to the biographer Cornelius Nepos:

Cornelī, tibi. ...

to you, Cornelius ...

The dative case has a range of uses, but it is reasonable to think of it as the ‘to’ or ‘for’ case, especially when the noun in the dative case is 1) a person and 2) on the receiving end of something, usually beneficial but occasionally disadvantageous. It is often found with the verb ‘give’ or ‘say’.

Caution

The English words ‘to’ and ‘for’ cover a wider range of ideas than the dative case in Latin. Note in particular that the dative would not be used in Latin to express the following:

- ‘I am going to the shops’. Here ‘to’ expresses the idea of motion towards something, not a person on the receiving end of anything. Latin would express ‘to’ in this instance with a preposition.

‘I want to speak with you this morning’. In this instance ‘to’ goes closely with the verb ‘speak’ (grammatically, they form an infinitive).

Practice

Activity 15: the dative case

a.

a. The Gauls provided supplies for Caesar.

b.

b. Caesar sailed to Africa.

c.

c. Agrippa gave a gift to his wife.

d.

d. Agrippa gave his wife a gift.

e.

e. I want to live well.

The correct answers are a, c and d.

a.

Correct.

c.

Correct.

d.

Correct. c. and d. mean the same.

3.3 ‘By’, ‘with’ and the ablative case

cui dōnō lepidum nouum libellum

āridā modo pūmice expolītum?

To whom do I give this charming new booklet

recently polished with dry pumice?

‘With’ is conveyed by the ‘ablative’ case, used here to convey the means or instrument by which something is done. Here the book has been polished ‘with’ or, less elegantly, ‘by’ or ‘by means of’ pumice stone. This use of the ablative case is typically found when 1) the verb is passive (‘he was hit with a sword’, ‘she was struck by a stone’) and 2) the noun is inanimate, i.e. not a living thing.

Examples

- multitūdō nōn ratiōne dūcitur sed impetū – the crowd is led not by reason but by impulse

When an action is carried out by a person, Latin uses the ablative case in combination with the preposition ‘ā’ or ‘ab’.

- Caesar ā Brūtō interfectus est – Caesar was killed by Brutus

Caution

The ablative case has a range of uses. It is difficult to single out one that characterises the ablative as a whole. You may come across the idea that the ablative is the ‘by, with or from’ case. There is some truth in this, although the best way to understand the ablative case is to work through examples of the different uses. Here we have concentrated on one important use, the ablative of means or instrument.

Practice

Activity 16: genitive, dative and ablative cases

Match the underlined word or phrase in English with the appropriate Latin equivalent.

A noun in the dative case

Caesar gave Cleopatra many gifts.

A noun in the genitive case

Antony’s slaves escaped.

A noun in the ablative case

The soldier was struck by an arrow.

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

A noun in the dative case

A noun in the genitive case

A noun in the ablative case

a.Antony’s slaves escaped.

b.The soldier was struck by an arrow.

c.Caesar gave Cleopatra many gifts.

- 1 = c

- 2 = a

- 3 = b

3.4 The first declension

The endings of Latin nouns are predictable. Each noun belongs to one of five patterns, called declensions. If you know the declension to which a noun belongs – in other words if you know its pattern – you can determine its possible endings.

The first declension

Table 6 below shows the genitive, dative and ablative case endings of the first declension, using the noun puella (‘girl’) as an example. Almost all nouns whose dictionary entry ends in -a belong to the first declension, i.e. they form endings in the same way as puella. This group includes most names of Roman women, such as Iūlia (‘Julia’) and Octāvia (Octavia).

Note that the ablative ending is a long ‘-ā’, not a short ‘-a’.

| case | ending | puella |

|---|---|---|

| singular | ||

| genitive | -ae | puellae |

| dative | -ae | puellae |

| ablative | -ā | puellā |

Activity 17

a.

genitive

b.

dative

c.

ablative

d.

none of the above

The correct answer is c.

a.

genitive

b.

dative

c.

ablative

d.

either genitive or dative

e.

none of the above

The correct answer is d.

d.

The context would help you determine whether the noun was in the genitive or dative case.

a.

Cleopatra

b.

Cleopatrae

c.

Cleopatrā

The correct answer is b.

3.5 The second declension

Table 7 below shows the genitive, dative and ablative case endings of the second declension, using the noun populus (‘people’) as an example. Again, we will concentrate on the singular endings. Most nouns ending in -us belong to the second declension. This group includes a large number of male praenōmina (forenames) such as Gāius, Lūcius and Marcus.

| case | ending | populus |

|---|---|---|

| singular | ||

| genitive | -ī | populī |

| dative | -ō | populō |

| ablative | -ō | populō |

Activity 18

a.

Antōnius

b.

Antōniī

c.

Antōniō

The correct answer is b.

a.

genitive

b.

dative

c.

ablative

d.

either dative or ablative

The correct answer is d.

d.

The context would help you decide which case.

Practice

Activity 19

Which Latin word could be used to translate the English word in bold?

a.

Antōnius

b.

Antōniī

c.

Antōniō

The correct answer is b.

b.

Yes, the genitive case is required.

a.

Cleopatra

b.

Cleopatrae

c.

Cleopatrā

The correct answer is b.

b.

Yes, the dative case is required.

a.

sagitta

b.

sagittae

c.

sagittā

The correct answer is c.

c.

Yes, the ablative case is required.

4 Latin verb endings

We saw earlier from Pliny and Catullus that Latin can express phrases like ‘I give’ and ‘you ask’ without using the personal pronouns ‘I’ and ‘you’. Although these words exist in Latin, they are usually omitted unless a writer wishes to emphasise them. The ending of the verb is enough to show who is doing the giving. Catullus could have written ego dōnō for ‘I give’, but dōnō is sufficient. Likewise Pliny refers to the request of his friend Tacitus with the words petis (‘you ask’), rather than tu petis.

4.1 Person and number

Examples

- perīculum videō – I see the danger

Octāvium exspectāmus – we await Octavius

in Italiam nāvigātis – you [plural] sail to Italy

The endings here express, among other things, the grammatical concept of person and number. There are three ‘persons’:

- the 1st person corresponds to the speaker (‘I’, or ‘we’)

- the 2nd person corresponds to the person addressed by the speaker (‘you’)

- the 3rd person refers to a third party (‘he / she / it’ or ‘they’). It is the standard person used in narrative prose, e.g. the descriptive passages of novels.

Persons can also be singular or plural in number, i.e. one or many. The difference between ‘I’ and ‘we’ is not one of person (they are both 1st person), but number. Table 8 below shows the possible combinations of person and number:

| person | number | |

| 1 | singular | I give |

| 2 | singular | you (singular) give |

| 3 | singular | he / she / it gives |

| 1 | plural | we give |

| 2 | plural | you (plural) give |

| 3 | plural | they give |

Latin verb endings provide a lot of information about a verb in addition to its number and person. This includes the tense of the verb, i.e. whether the action was done in the present (‘I give’), the past (‘I gave’) or the future (‘I will give’). We will not cover this in detail here. If you study Latin, you will be introduced to the different features of verbs and their endings gradually and over an extended period of time. For the moment, be aware that word endings provide important information for both verbs and nouns.

4.2 The first conjugation

The endings of Latin verbs, like those of nouns, are predictable because verbs belong to one of four groups, known as conjugations. A conjugation is a pattern of verb endings, just as a declension is a pattern of noun endings.

The verb dōnō (‘I give’, ‘I present’) belongs to the first conjugation. It takes the following endings in the present tense (strictly speaking, the present indicative active):

| Number and person | Latin | English equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| singular | ||

| 1 | dōnō | I give |

| 2 | dōnās | you (singular) give |

| 3 | dōnat | he / she / it gives |

| plural | ||

| 1 | dōnāmus | we give |

| 2 | dōnātis | you (plural) give |

| 3 | dōnant | they give |

Activity 20

a.

Yes

b.

No

The correct answer is a.

Answer

Yes, but nothing like to the same extent as Latin. With ‘he/she/it’ or a singular noun (e.g. ‘the dog’, ‘the cat’), English verbs in the present tense add ‘-s’ (‘she walks’ or ‘the cat skulks’ ).

Most English verbs also change their ending in the past tense (i.e. when describing events in the past) by adding ‘-ed’, thus ‘I walk’ becomes ‘I walked’. Some verbs undergo a more radical change, e.g. ‘I eat’ becomes ‘I ate’.

Practice

Activity 21

Using the conjugation table (repeated below), match the following first conjugation verbs with their English equivalents.

amant

they love

rogās

you (singular) ask

ambulāmus

we walk

festīnat

she hurries

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

amant

rogās

ambulāmus

festīnat

a.you (singular) ask

b.she hurries

c.they love

d.we walk

- 1 = c

- 2 = a

- 3 = d

- 4 = b

| Number and person | Latin | English equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| singular | ||

| 1 | dōnō | I give |

| 2 | dōnās | you (singular) give |

| 3 | dōnat | he / she / it gives |

| plural | ||

| 1 | dōnāmus | we give |

| 2 | dōnātis | you (plural) give |

| 3 | dōnant | they give |

4.3 Agreement

So far, we have concentrated on verbs with personal pronouns as subjects (‘I’, ‘you’, ‘we’, etc.). A more common scenario, especially in descriptive prose composed by historians such as Livy and Tacitus, is for the subject to be a person or a thing (‘the consul’, ‘the dog’, ‘the cat’, and so on). In this situation, the third person forms of the verb are used. If the noun is singular, the verb form is the third person singular. If the noun is plural, the third person plural form of the verb is used.

3rd person verbs

singular

- pugnat – he/she/it fights.

- Antōnius pugnat – Antonius fights

plural

- pugnant – they fight

- Rōmānī pugnant – the Romans fight

This is the grammatical concept of agreement. A singular noun is accompanied by a third person singular verb; a plural noun by a third person plural verb.

Activity 22

a.

festīnō

b.

festīnat

c.

festīnāmus

d.

festīnant

The correct answer is d.

a.

festīnō

b.

festīnat

c.

festīnāmus

d.

festīnant

The correct answer is b.

5 Simple sentences

To construct a complete sentence you need at least a verb (e.g. ‘walks’, ‘jogs’, ‘runs’) and a subject (the person or thing doing the ‘walking’, ‘jogging’ or ‘running’).

Subject plus verb

- George walks.

- Sheila jogs.

- Sam runs.

5.1 Subject and object in English

Certain verbs also demand an object to make the meaning complete. The objects are highlighted in the following sentences.

Subject, verb and object

- George carried the shopping.

- Sheila brought cake.

- Sam found happiness.

Sentences of this form are common in both English and Latin. They are, however, constructed according to quite different principles. Let us consider English first.

Activity 23

Look at the sentence below and answer the questions that follow:

Tiberius loves Livia

Part 1

1. Identify the subject, verb and object.

Subject

Tiberius

Verb

loves

Object

Livia

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

Subject

Verb

Object

a.Tiberius

b.loves

c.Livia

- 1 = a

- 2 = b

- 3 = c

Part 2

2. What tells you that Tiberius is the subject of the sentence and not Livia?

Answer

The order of the words. In English, the word order is usually a subject followed by a verb followed by an object (if the sentence has an object. Not all do). This is why English belongs to the category of ‘Subject – Verb – Object’ languages, or ‘SVO’ languages for short.

Part 3

3. What happens to the meaning of the sentence if you swap the words Tiberius and Livia?

Answer

Livia becomes the subject and Tiberius the object, i.e. the roles of Tiberius and Livia are reversed.

This use of word order to provide information about the role of nouns has one important consequence. It means that the order of words in English, unlike Latin, has to be fairly rigid if sentences are to be understood.

5.2 Subject and object in Latin

In Latin, the subject and object are indicated not by their position in the sentence but by the ending of the word.

Tiberius Līviam amat – Tiberius loves Livia

In Latin the subject is placed in the nominative case, the object in the accusative case. Nouns are recorded in the dictionary in the nominative case, e.g. puella or populus. As a result, if you are familiar with a Latin word you already know its nominative singular form. Nouns in the accusative case are formed using a variety of endings across the five declensions. However, singular nouns in the accusative case almost always end in a vowel followed by the letter ‘m’, like Līviam in the example.

The chief use of the nominative and accusative cases is to mark subjects and objects. It is therefore helpful to think of the nominative case as the ‘subject’ case, and the accusative case as the ‘object’ case.

Activity 24

If subjects and objects in Latin are marked by word ending rather than word order, what, if any, is the difference in meaning between the following sentences?

1. Tiberius Līviam amat.

2. Līviam Tiberius amat.

3. amat Tiberius Līviam.

Answer

There is no difference of meaning because the word endings are identical in all three sentences. Tiberius is always the subject; Līviam is always the object.

There may, however, be a slight change of emphasis. By shifting the object to the front, the writer of the second sentence might be trying to emphasise Livia. You could bring this out in English by translating, ‘It is Livia whom Tiberius loves’.

5.3 Word ending in English

Although English uses word order to indicate subjects and objects, traces of something like ‘nominative’ and ‘accusative’ cases are still visible in English personal pronouns. That is to say, English personal pronouns operate like Latin nouns because their role is indicated by their form. In the following example, to change the subject and object, you must change not only the word order but also the form of the pronouns ‘I’ and ‘he’.

English personal pronouns as subjects and objects

I love Livia → --> Liva loves me.

He loves Livia → --> Liva loves him.

Activity 25

Do other English pronouns besides ‘I’ and ‘he’ change form when used as objects?

Answer

Yes.

| Subject | Object |

|---|---|

| I | me |

| he | him |

| she | her |

| we | us |

| they | them |

‘You’ takes the same form whether it is subject or object, but the archaic form ‘thou’ (subject) becomes ‘thee’ when used as an object. Note also the relative pronoun ‘who’ (subject) and ‘whom’ (object). These examples are remnants of what was once a more widespread use of cases by English nouns.

You have already seen that the use of word endings in Latin allows the order of words to be less rigid. This can also occur in English, especially where personal pronouns are involved.

Activity 26

In what order are the subject, verb and object in the following sentences?

a.

Subject – Verb – Object

b.

Subject – Object – Verb

c.

Object – Subject – Verb

The correct answer is b.

Answer

I (subject) thee (object) wed (verb).

a.

Subject – Verb – Object

b.

Subject – Object – Verb

c.

Object – Subject – Verb

The correct answer is c.

Answer

keys (object) he (subject) bore (verb)

The golden rule when shifting English words into unexpected positions is to keep the meaning of the sentence clear. The use of subject forms (‘I’ and ‘he’) and object forms (‘thee’) help to clarify the meaning in the above examples, in spite of the unusual word order.

5.4 Word order in Latin

Latin writers could use the flexibility of Latin word to achieve some striking effects. Virgil’s epic poem Aeneid, for example, begins with two nouns in the accusative case: arma (‘arms’, ‘weapons’, i.e. war) and virum (‘a man’, i.e. the hero of the poem, Aeneas).

arma virumque cano ...

I sing of arms and a man ...

This order of words allows the topic of the poem to take centre stage. It also enables Virgil to echo Homer, who started his Iliad and Odyssey in a similar way, with nouns in the accusative case indicating his subject matter.

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος ...

mēnin aeide thea Pēlēiadeō Achilēos ...

Sing, goddess, of the anger of Achilles, son of Pelias ...

ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, μοῦσα, πολύτροπον ...

andra moi ennepe, mousa, polytropon ...

Tell me, Muse, of the man of twists and turns ...

This use of word order creates such an impact that English translators have sometimes opted to preserve it. Thus Robert Fagles in his translation of Aeneid writes ‘Wars and a man I sing ...’, which is about as close to Virgil’s Latin as it is possible to get.

5.5 Practice

Nouns in the nominative singular exhibit a great variety of endings, but in the first declension they always end in ‘-a’ and in the second they mostly end in ‘-us’. Nouns in the accusative singular across all declensions almost always end in a vowel followed by the letter ‘m’.

| Case | 1st declension | 2nd declension |

|---|---|---|

| singular | ||

| nominative | puella | populus |

| accusative | puellam | populum |

Activity 27

Who is the subject in the following sentences?

a.

Antony

b.

Cleopatra

The correct answer is a.

a.

Yes, Antōnius is in the nominative case and is therefore the subject.

a.

Antony

b.

Cleopatra

The correct answer is a.

a.

Yes, Antōnius is in the nominative case and is therefore the subject.

a.

Antony

b.

Cleopatra

The correct answer is b.

b.

Yes, Cleopatra is in the nominative case and is therefore the subject.

Activity 28

Which word could complete the following sentences?

a.

Antōnium

b.

Antōniī

c.

Antōnius

The correct answer is c.

c.

Yes, Antōnius is in the nominative case and would therefore provide a subject for amat.

a.

Cleopatra

b.

Cleopatram

c.

Cleopatrae

The correct answer is b.

b.

Yes, Cleopatram is in the accusative case and would therefore provide an object for amat.

5.6 Declensions summary

We are now in a position to summarise the case endings for puella and populus. Table 12 below includes plural endings as well as singular.

| Case | 1st declension, puella | 2nd declension, populus |

|---|---|---|

| singular | puella | populus |

| nominative | puella | populus |

| accusative | puellam | populum |

| genitive | puellae | populī |

| dative | puellae | populō |

| ablative | puellā | populō |

| plural | ||

| nominative | puellae | populī |

| accusative | puellās | populōs |

| genitive | puellārum | populōrum |

| dative | puellīs | populīs |

| ablative | puellīs | populīs |

Latin also has a ‘vocative’ case, used for direct address, e.g ō puella, ‘girl!’, … . The ending is routinely the same as the nominative, the notable exception being 2nd declension singular nouns, where -us usually becomes -e, as in the dying words of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: et tu, Brūte? (‘You too, Brutus?’).

6 Reading Latin

Learning a language inevitably involves learning the meanings of individual words. You will be familiar with this process if you have studied a foreign language before. Perhaps you have created flash cards or drawn up lists of those troublesome words that, for some reason, never seem to stick in the memory. Latin is no exception in this respect, although in learning Latin you have the advantage that many Latin words are the ancestors of English ones.

6.1 Words

The following activity will enable to you explore the links between some Latin and English words.

Activity 29

Try to find at least one English word derived from the vocabulary used in the passages of Pliny and Catullus (listed in tables 13 and 14 below). Write down your answers in the box provided.

| Latin words |

|---|

| petō – ‘I seek, ask’ |

| auunculus – ‘uncle’ |

| exitus – ‘departure’, ‘death’ |

| scrībō – ‘I write’ |

| uērus – ‘true’ |

| trādō – ‘hand over’, ‘transmit’ |

| posterī – literally ‘those who come later’, i.e. ‘future generations’ |

| possum – ‘I can’ |

| Latin words |

|---|

| dōnō – ‘I give’, ‘I present’ |

| nouus – ‘new’, ‘novel’ |

| āridus – ‘dry’ |

| modo – ‘recently’ |

Answer

The list below is not complete, but covers some of the most obvious derivations.

| Pliny | English derivations |

|---|---|

| petō – ‘I seek, ask’ | petition |

| auunculus – ‘uncle’ | avuncular |

| exitus – ‘departure’, ‘death’ | exit |

| scrībō – ‘I write’ | scribe, script |

| uērus – ‘true’ | veracity, verify, veritable |

| trādō, ‘hand over’, ‘transmit’ | tradition |

| posterī, literally ‘those who come later’, i.e. future generations | posterity |

| possum, ‘I can’ | possible |

| Catullus | |

|---|---|

| dōnō, ‘I give’, ‘I present’ | donate |

| nouus, ‘new’, ‘novel’ | novel |

| āridus, ‘dry’ | arid |

| modo, ‘recently’ | modern |

The study of Latin vocabulary can also help your understanding of English words. Look, for example, at the abstract English nouns in Table 15 below, which each derive from a Latin word whose meaning is quite specific.

| English | Latin |

|---|---|

| equality | aequus – ‘flat’, ‘level’ |

| essence | esse – the Latin verb ‘be / is’, i.e. the ‘is-ness’ of a thing |

| humility | humilis – ‘low’ (also ‘humus’, ‘ground’) |

| quantity | quantus – ‘how much?’ |

| quality | quālis – ‘of what kind?’ |

| ubiquitous | ubīque – ‘everywhere’ |

6.2 Beyond words

Words are the building blocks of language. It therefore makes sense to devote plenty of time to studying them. Nevertheless, understanding the meaning of words is not enough to allow you to read Latin, or any other language, with fluency and confidence.

What else is needed? Many factors are relevant here, including an appreciation of grammar and an exposure to a great deal of Latin. We will close by highlighting just one important skill possessed by experienced readers, namely the ability to see not just words but groups of related words. As a fluent reader of English this will be second nature to you. Without it, you would find the process of reading unbearably slow and laborious. Look, for instance, at the opening sentence of Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

In the second century of the Christian Era, the Empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind.

This sentence can be broken into a number of smaller chunks. Even if you know very little about grammar, you will instinctively recognise that some sets of words form natural groups, such as:

- in the second century

- the Empire of Rome

- the fairest part of the earth

- the most civilised portion of mankind

On the other hand you would be very unlikely to take the words ‘of Rome comprehended the’ as a unit. Why? Because it is incomplete and therefore not meaningful in its own right.

6.3 Larger units

The ability to recognise words that relate to one another is an important part of fluent reading. It takes some time to acquire this skill, but it is useful to be aware of it as a goal at an early stage. Even spotting two or three related words represents an advance over reading word by word and can help to speed up the reading process. Here are a few word groups that have been mentioned so far:

| a preposition and its noun | to the lighthouse |

| an adjective and its noun | green onions |

| two nouns, one in the genitive case | Martha’s brother |

| a subject, a verb and a direct object | the dog chased the cat |

Let us look more closely at one example, noun−adjective pairs.

Activity 30

Find four examples of adjectives and their nouns in the passage from Gibbon.

In the second century of the Christian Era, the Empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind.

Answer

In the second century of the Christian Era, the Empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind.

Note that in the above passage the adjectives are adjacent to their nouns, the standard pattern in English. This is frequently true of Latin too, as with Catullus’ ‘charming new booklet’ (lepidum nouum libellum). But the noun−adjective pair can also be separated, and frequently is in Latin poetry. Remember the ‘dry pumice’ in Catullus, split by the word modo (‘recently’).

āridā modo pūmice expolītum?

Here are some more examples, the last of which contains two noun-adjective pairs.

magnā cum laude – ‘with great praise’

altae moenia Rōmae – ‘the walls of lofty Rome’ (Virgil, Aeneid, 1.7)

aurea purpuream subnectit fībula vestem – ’a golden brooch binds her purple cloak’ (Virgil, Aeneid, 4.139)

In Latin, as you might have suspected by now, the word endings provide you with important clues for relating words to one another. The meaning usually also provides some clue, but it is only the meaning combined with the word order that really decides the issue. In the final example, the meaning would allow a ‘golden cloak’ and a ‘purple brooch’, but the word endings establish that the brooch is golden (aurea ... fībula) and the cloak purple (purpuream ... vestem).

Key point

The study of small units like words and word endings is a central part of learning Latin.

But reading a Latin text also involves seeing how the words fit together into larger units such as phrases, clauses and indeed whole sentences. The word endings can help you spot these larger units, by allowing you to see which words relate to one another. If you can start to blend these approaches together – the small and the large – then you really will be on your way to reading Latin like a citizen of ancient Rome!

6.4 Closing thoughts

We began with parallel texts and the act of reading an English translation alongside its Latin counterpart, looking across from one to the other and back again. We saw that this was not purely a matter of mapping one text to another word by word. We explored the reasons for this and traced them to basic differences in the workings of the two languages. In particular, we noted the role of word endings in Latin, a role fulfilled in the English language either by word order or by the presence of words not required in Latin.

If the specific endings of nouns and verbs are already starting to fade from memory, not to mention the terminology of datives, genitives, declensions and conjugations, do not worry at this stage. If you choose (or have already chosen) to study Latin, these will be reintroduced to you gradually and you will be given many opportunities to reinforce what you have learned through practice and by applying your knowledge to the reading of Latin texts. We do, however, hope that after working through this material, you have a deeper understanding of why these details matter and how they contribute to the goal of understanding Latin.

7 Beginning Greek

Your first encounter with a Greek text is likely to take place through an English translation. To delve deeper, the next step might be to acquire the Greek text and a Greek−English dictionary. With these in hand you can inspect the text and translation in parallel, trying to relate one to the other.

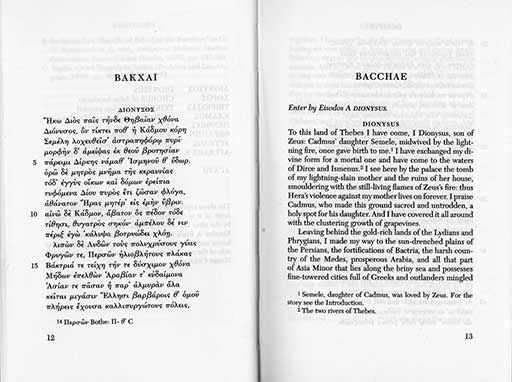

This is an image of an open book. The left-hand side is page 12 and the right-hand side is page 13.

The left-hand side is written in Greek. There are 21 lines of Greek text beneath the title. The line numbers 5, 10 and 15 are indicated on the left-hand side of the text.

The right-hand page is written in English. The title is BACCHAE. The text below begins with a stage direction followed by seventeen lines by Dionysus. There are no line numbers but two footnotes can be seen at the bottom of the page.

You can make some headway with this approach. It has the great advantage of allowing you to work with ‘real’ Greek; that is, Greek composed by a Greek speaker for a Greek-speaking audience. Eventually, however, its limitations will become clear. Two problems stand out in particular:

- An English translation is likely to contain more words than its Greek equivalent.

- English word order will probably differ from Greek.

These problems arise because English and Greek work according to different principles. If you can grasp these principles and their implications, you will have taken an important step on the path to reading Greek as Greek instead of through the medium of English.

In the following sections, you will see these principles at work in an extract from the Bacchae of Euripides. Ideally you will be familiar with the Greek alphabet and understand the basics of Greek pronunciation, perhaps from working through the relevant sections of ‘Introducing Ancient Greek’. However, all Greek on this site is transliterated, which means you can acquire some appreciation for the way the Greek language works without knowing the Greek letters.

7.1 Parallel text: Euripides

Here are the first three lines of the prologue from Euripides’ play, Bacchae, together with notes on individual words and phrases (see Table 16). Spend a couple of minutes familiarising yourself with it and seeing how much, if any, you can understand. Then attempt to answer the questions that follow.

Euripides, Bacchae, 1.1−3.

The god Dionysus (Bacchus) announces his arrival at the Greek city of Thebes.

English

I, son of Zeus, have reached this land of Thebans, Dionysos, whom the daughter of Kadmos, Semele, once bore, brought to labour by lightning-bearing flame.

Greek

ἥκω Διὸς παῖς τήνδε Θηβαίων χθόνα

Διόνυσος, ὃν τίκτει ποθ᾽ ἡ Κάδμου κόρη

Σεμέλη λοχευθεῖσ᾽ ἀστραπηφόρῳ πυρί

transliteration

hēkō Dios pais tēnde Thēbaiōn chthona

Dionysos, hon tiktei poth' hē Kadmou korē

Semelē locheutheis' astrapēphorōi pyri

| Greek | English | Dictionary entry |

|---|---|---|