Clues to interpretation

We shall focus on Merry Company (Figure 15), a painting by the little-known Haarlem artist, Isaac Elias, dating from c.1620, since de Jongh presents his analysis of this painting as a ‘demonstration’ of his theory of seeming realism.

The painting depicts a group of figures engaged in a variety of activities, seated or standing around a table in a well-appointed interior. The title, Merry Company, would have been given at a later date, and is often used to describe paintings that show finely dressed people relaxing together, eating, drinking and sometimes playing music. De Jongh begins his analysis by drawing attention to the two paintings that are shown hanging on the wall behind the figures. These are difficult to make out in reproduction, and are of small size even in the original, but the rectangular picture on the left depicts the biblical theme of the Deluge and the oval picture on the right a battle scene. De Jongh describes the device of including a painting-within-the-painting as a traditional seventeenthcentury means of ‘admonishing’ the depicted figures. He notes that there is nothing ‘merry’ about these two images: the Deluge alludes to Divine punishment for the sinfulness of mankind, while the battle scene can be related to biblical texts that describe life on earth as a struggle or conflict in which our moral fortitudeis tested.

De Jongh’s second main contention is that there is an important difference between the two figures standing on the right and the other figures in the painting. He identifies them as a couple and observes that they do ‘not partake in the meal, but rather stand and look out of the picture plane toward the viewer’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 24). Once we note this difference, it is possible to interpret the scene beside them not as a realistic representation of figures who are in the same room as them at the same time, but as an allegorical representation of the temptations facing a wedded pair, who must use their resolve to ensure the virtuous conduct of their future life together. In particular, de Jongh claims that the diners in the painting are an allegory of the Five Senses of sight, smell, taste, touch and hearing, and that each of these would have been understood by contemporary viewers as symbolising various sinful possibilities. The diners function both as a ‘moral mirror’ and as ‘hidden persuaders’, who prompt the couple – and by extension the viewer – to resist the seduction of worldly pleasures.

In support of this interpretation, de Jongh observes that whereas in other countries ‘allegorical concepts were almost always cloaked in the form of fantastical personifications, in Holland they generally appeared as “normal” people in everyday garb’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 21). The meanings of such paintings are thus ‘hidden’ in a double sense. On the one hand, they were veiled or disguised for contemporary viewers, who were expected to use clues within the painting, such as the pictures on the wall, to work out the moral message. On the other hand, they are hidden in a second and stronger sense from later viewers, who take Dutch paintings to be straightforwardly ‘realistic’ depictions of scenes from everyday life.

Once the viewer is alert to the possibility of hidden meanings, even familiar paintings can start to look very different. Some art historians have suggested that we need to look for a clavis interpretandi or ‘key to interpretation’, which is often tucked away in a remote corner. A particularly telling example is given by de Jongh in his analysis of a painting by Jan Steen (1626–79), which he refers to by the title The So-Called Brewery of Jan Steen (Figure 16).

Activity 1

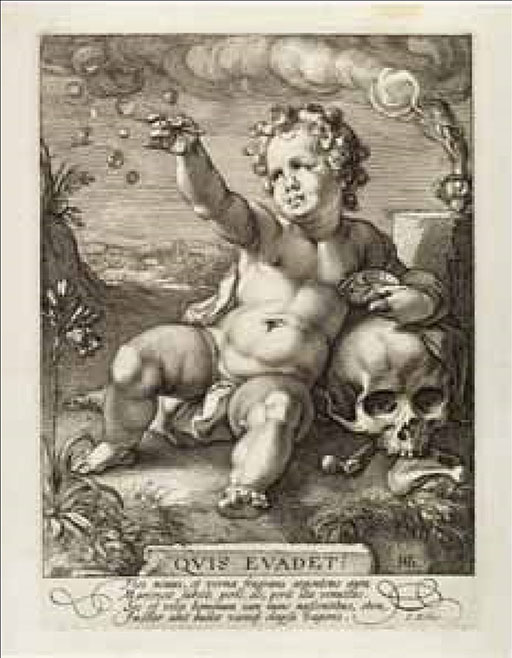

Look carefully at the reproduction of this painting in Figure 16 and say what you think the subject of the painting might be. Then look at Figure 17, which shows a detail of the painting in which a boy, tucked away in the loft, blows bubbles next to a skull. What meaning might be attributed to this motif and how might this influence your interpretation of the painting?

Discussion

The painting depicts a spacious interior, illuminated by a window to the left, in which several groups of people are engaged in various activities. It looks more like a room in a domestic house than a brewery (the title may have been given because Jan Steen’s father was a brewer and the painter himself for a short time ran a brewery). However, the room is very large by modern standards and it is crowded with figures who are shown relaxing with music, food and other diversions. On the left, there is a seated man eating oysters, more of which are being prepared by a young woman in the foreground. On the right are figures seated at a table, including a woman singing with an oyster in her left hand, and a lute player half turned towards her. The composition of the painting encourages us to move from one group of figures to another to discover what each is doing, and we are rewarded by plenty of incidental detail, such as the boy encouraging a cat to ‘dance’ on its hind legs. It would seem, then, that the subject of the painting is merry-making in one form or another, and that we are offered a view of Dutch citizens contentedly fulfilling their hours of leisure. The boy blowing bubbles in the upper storey seems fully continuous with this theme until we notice the skull beside him. In western painting, the incorporation of a skull into a picture often serves as a memento mori, a ‘memento of death’, which reminds the viewer of the transience of worldly pleasures. The presence of this overtly symbolic motif suggests that the painting may not be a straightforwardly ‘realistic’ representation of an everyday scene and alerts us to the possibility that it may contain a moral dimension.

In his discussion of this painting, de Jongh argues that the depiction of the boy blowing bubbles is closely linked to the memento mori theme. He interprets it as a visual representation of the Latin phrase homo bulla, ‘man is [fragile] as a soap bubble’: just as a bubble floats into the air and catches the radiance of light, only to burst into nothing, so human life is brief and evanescent. The location of this image near the centre of the painting, at a point where several lines converge, gives credence to de Jongh’s proposal that Steen has provided us with a necessary clue to interpret the painting. The prevalence of this image in other paintings and in emblem books and engravings, where its meaning was sometimes made explicit through textual commentary (Figure 18), suggests that contemporary viewers would have been able to discover this clue. De Jongh also points out that oysters, which were thought to be an aphrodisiac, were popularly associated with licentiousness, and that the female figure standing by the window is probably a matchmaker carrying out her trade. He therefore concludes that the subject of the painting is contained in its moralising message: it condemns the frivolousness of the various pastimes it depicts.

De Jongh’s analysis is open to challenge. In particular, it is curiously at variance with the mood of the picture and the lively way in which the artist has painted such a busy scene crammed with life. However, whether or not one agrees with his conclusions, his approach successfully draws attention to the artificiality of the representation. We are led to wonder why certain objects, such as cups and a spoon, are scattered on the floor and whether a milk pail would have been left standing unattended where it could easily be knocked over. It is as if each object or figure in the painting has been carefully placed to invite interpretation and is thus the result of deliberation by the artist rather than a reflection of the haphazard contingencies of a ‘slice of life’. Most striking of all is the large piece of cloth draped over the balcony, which can be read both as a naturalistic representation of an object within the depicted scene and as a curtain in front of the painting that is pulled up in a theatrical way to reveal what lies behind.

Having looked closely at this painting by Jan Steen, we can now return to his The Effects of Intemperance (Figure 5). What initially appears to be a ‘realistic’ image of a scene from everyday life turns out to be full of artful contrivances. That the woman’s slumber is caused by the effects of alcohol is suggested by the image of the girl encouraging a parrot to drink from a wine glass. The resulting disorder is illustrated through the small child picking the woman’s pocket as she sleeps and the older children feeding a pie to the cat. The pig standing before a rose refers to a Dutch proverb about tossing roses before a swine, whose meaning is analogous to the English proverb ‘pearls before swine’. Above the woman’s head hangs a basket, which contains a birch switch, a crutch and a leper’s clapper, objects associated with punishment, infirmity and disease. In this case, it seems clear that the painting does contain a moral message or, at least, takes moral themes as part of its subject matter. Although the clues to interpretation can scarcely be said to be ‘hidden’, the baleful consequences of intemperance are shown through everyday actions and objects such as might have been seen at the time Steen was painting rather than through ‘fantastical personifications’ based on classical mythology.

So far we have only considered examples of interior and exterior scenes with multiple figures. However, de Jongh contends that his analysis of the ‘seeming realism’ of Dutch seventeenth-century painting can also be applied to other types of painting, including portraiture, still life and landscape painting. Artists who specialised in ‘flower pictures’ depicted costly bouquets of rare and exotic flowers with the occasional addition of a stray butterfly or beetle. Although these bouquets look highly realistic, and seem to have been painted from life, they frequently include flowers that bloom at different times of the year and so could not have been seen together. De Jongh contends that flower pictures would have been understood in relation to contemporary mottos such as Sic transit gloria mundi (‘So passes away the glory of the world’) and were intended to evoke an awareness of transience. In support of this contention he draws attention to the figure and inscription embossed on the terracotta pot depicted in Jan van Huysum’s Flower Still Life (Figure 19). This contains part of a verse from Matthew 6, ‘Consider the lilies of the field; even Solomon in his glory was not arrayed like one of these.’ However, de Jongh notes that such overt references were unusual and that ‘symbolism in seventeenth-century flower pieces is usually cloaked in a realistic disguise’ (Jongh, 1971, p. 29). He contends that even without the presence of a ‘key to interpretation’, such as van Huysum provides, educated contemporary viewers would have been expected to grasp the connection between the ephemeral beauty of flowers and the brevity of human life. De Jongh’s account of the deeper significance accorded to flower paintings is at variance with the low evaluation accorded to still-life painting within the academic hierarchy of the genres, which was still upheld by Reynolds when he travelled to Holland. We might also ask whether there may have been other, less weighty reasons why affluent city dwellers wanted to place images of flowers on their walls. Horticulture was highly developed in the densely urbanised Netherlands and flowers such as tulips were greatly prized and sought-after.