3.8 Transcending the Romantic-classic divide

Much of the ground for the reception of Sardanapalus had now been prepared. The classic-Romantic divide, with David’s followers on one side and Gros and Géricault on the other, was already well established by the time Delacroix produced his painting of mass suicide. Contemporary viewers would have detected Romantic allegiances in, for example, the horse and black slave, probably influenced by Gros. And yet Delacroix never came to terms with the perception of himself as the enemy of classicism. It bothered him that he should be regarded as someone out of control, swept along by the energies and eddies of an uncontrollable genius. He was stung by reactions to what he perceived as a generally successful work:

I am sick of this whole Salon. They’ll end by making me believe that I’ve had a real fiasco. And yet I’m not entirely convinced. Some say it’s a total failure, that The Death of Sardanapalus means the death of the Romantics, since that’s what they call us; others bluntly declare that I’m inganno [in error], but that they’d rather be wrong with me than be right like a thousand others who have good sense on their side, if you like, but who deserve damnation in the name of the soul and of the imagination. My own opinion is that they’re all idiots, that this picture has both qualities and faults, and that if there are some things in it that I could wish better done, there are plenty of others that I hold myself fortunate to have done and that they might well wish to have equalled … It’s all quite pitiful and would not deserve a moment’s attention except in so far as it directly jeopardizes my wholly material interests, in other words, cash.

(Letter to Charles Soulier, Paris, 11 March 1828, in Stewart, 1971, pp.145–6)

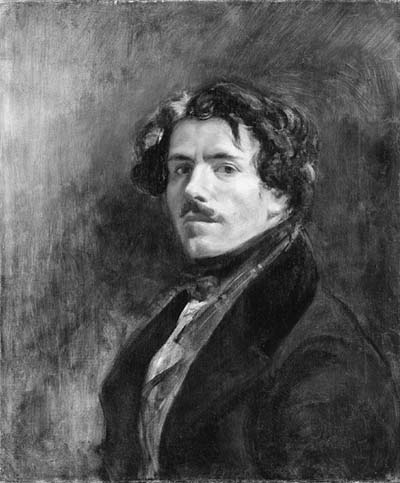

This final remark by Delacroix was prompted, perhaps, by the fact that he saw the state as the only realistic purchaser of a painting of this grandeur. Indeed, this was the situation faced by most history painters of the day working outside the remit of Church or private commissions. The artist’s journal shows him to be a shrewd book-keeper, market researcher and businessman. Far from considering himself the witless victim of artistic delirium, Delacroix was, by the mid-1820s, an accomplished socialite – a regular attender at Parisian salons, acquiring expertise in the kind of self-publicity that would flourish later in his career. He assumed the role and appearance of an English dandy, undemonstrative and impassive (see Figure 7). Furthermore, his method of producing paintings was painstaking and founded on fine judgement: he usually made preparatory sketches, both compositional and of individual figures, based on the observation of models. In other words, his work does include a measure of the refined study of nature, control and intelligence expected of the classical artist. We can see from this how each art form develops its own way of allocating labels to styles. Delacroix greatly admired Mozart’s music, preferring it to Beethoven’s, whose ‘wild originality’ was legendary. Beethoven’s music was, he felt, ‘obscure and … lacking in unity’ – the reason being that Beethoven ‘turns his back on eternal principles: Mozart never’ (quoted in Vaughan, 1978, p.246). The eternal and the unifying: these were the hallmarks of classical order and composition. While Delacroix did admire, in the work of musicians, artists and writers such as Beethoven, Rubens and Shakespeare, qualities of sketchiness and the unfinished, he nevertheless felt that the consummate, classical art of Racine and Mozart represented a form of eternal beauty (Hannoosh, 1995, pp.71–4).