1 Paintings at the Louvre

1.1 The state as patron

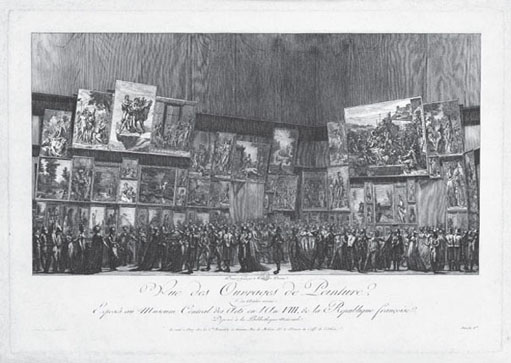

Most of the history paintings in the Daru and Mollien rooms have been in the Louvre, a royal palace that was turned into a museum in 1793, since the nineteenth century. Many of them were commissioned by the French state, which has a long tradition of promoting the arts for the sake of the personal glory of the ruler and the prestige of the nation as a whole. Many of the others were acquired by the state after being shown at the Salon, the public exhibition held at the Louvre every year or two during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (named after the room in which it was held the salon carre). Works of art that had been commissioned by the state would also be exhibited in the Salon, so that the public could see the results of official patronage. Free entry attracted huge crowds and meant that the Salon audience was socially pretty diverse (see Figure 1). These institutional factors played a decisive role in shaping the very nature of French art during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The huge history paintings on display today in the Daru and Mollien rooms would not have come into existence without the state as actual patron or potential buyer: they are mostly too large to go anywhere but a museum or other public building. Moreover, the knowledge that his painting was going to be exhibited at the Salon meant that an artist would be conscious of the need for eyecatching effects in order to compete with all the other paintings hanging on the walls for the attention of the public. It is important to keep these points in mind when analysing French paintings of this period.

Click to view a larger version of Figure 1, View of the Salon [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , 1799.

Between them, these galleries allow visitors to trace the chronological development of French painting from Neoclassicism (the term applied to late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century painting in the classical style) in the Daru room to Romanticism in the Mollien room. We can gain some sense of the changes between NeoClassicism and Romanticism by means of a comparison between a history painting by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), the principal exponent of Neoclassicism, and one by Eugene Delacroix (1798–1863), the leading French Romantic painter. David's Oath of the Horatii, exhibited in the Salon of 1785 (see Plate 1), depicts an example of patriotic virtue from ancient Roman history with great clarity and simplicity. The statue-like figures stand out against a dark background, the setting is a plain box-like space, the colour range is limited and the paint surface smooth, almost photographic (though it should be noted that this effect is heightened by the fact that what you are looking at is, in fact, a photograph). By contrast, Delacroix's Massacres of Chios, exhibited in the Salon of 1824 (see Plate 2), depicts an episode from the Greek War of Independence, which was going on at the time. It has a vertical rather than a horizontal format, which means that the figures are crowded into a narrow foreground in a somewhat confusing way. Rather than being strong and heroic, like the main figures in David's painting, they are the helpless victims of Turkish oppression. Behind them, the open landscape appears very much as a flat backdrop. Despite its grim subject, the painting has a certain picturesque appeal, thanks to the exotic costumes, light tonality, vivid colours and loose handling of paint. Overall, it can be said that this work retains the ambitions of a history painting but breaks with the aesthetic and moral idealism traditionally expected of the genre.

Click to see plate 1 Jacques-Louis David, The Oath of the Horatii, oil on canvas, 329.9 x 428.8 cm, Louvre, Paris. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

Click to see plate 2 Eugène Delacroix, Massacres of Chios, 1824, oil on canvas, 417.2 x 354 cm, Louvre, Paris. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

A key figure in French painting between David and Delacroix is Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835), whose two most famous works, Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken of Jaffa (1804) and Napoleon Visiting the Field of the Battle of Eylau (1808), now hang in the Mollien room (Plates 3 and 4). A former pupil of David, Gros turned to the depiction of current political and military events in a lively, colouristic fashion in response to the propaganda demands of the Napoleonic regime. For Delacroix, Gros's work represented a dazzling achievement that he aspired to emulate, and, as a young man who came of age after the fall of the empire, he envied the older artist for having lived in an era of spectacular military exploits. In 1824 he wrote: ‘the life of Napoleon is the epic of our century for all the arts’ (Delacroix, 1938, p.78). Jaffa and Eylau continue to be admired today as pioneering examples of the Romantic style and, as such, are distinguished from most other Napoleonic propaganda painting, which seems conventional and uninspired by comparison. It has been argued that they ‘enshrine not only Napoleon's heroism but also Gros's misgivings’ and thus introduce ‘an element of fundamental personal doubt’ into French history painting (Brookner, 1980, p.161), despite the fact that there exists no written evidence to suggest that the artist was at all disillusioned with Napoleon. Underlying this statement is the assumption that a great work of art must be the independent creation of an autonomous genius and cannot simply have been painted according to official dictates. This conception of artistic creation as self-expression in fact crystallized during the period that we are considering, and is one of the defining features of Romanticism as a broad cultural movement.

Click to see plate 3 Antoine-Jean Gros, Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken of Jaffa, 1804, oil on canvas, 532.1 x 720cm, Louvre, Paris. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

Click to see plate 4 Antoine-Jean Gros, Napoleon Visiting the Field of the Battle of Eylau, 1808, oil on canvas, 521 x 784 cm, Louvre, Paris. Photo: Bridgeman Art Library

In this course we examine a range of Napoleonic imagery by David, Gros and a number of other artists. We begin with relatively simple single-figure portraits and moving on to elaborate narrative compositions such as Jaffa and Eylau As you saw in the introduction to the course, we have three key aims.

The first is to develop your skills of visual analysis and to show how a painting's form and content together produce its meaning. In doing so, we illuminate the broad cultural shift from the Enlightenment to Romanticism as it played out in Napoleonic painting.

The second aim is to examine the relationship between art and politics. We will examine how painting came to be used and controlled by the Napoleonic regime for propaganda purposes. As you will see, the fundamental problem driving Napoleonic propaganda was one of political legitimation: how to provide ideological justification for a leader who had seized power and whose rule rested ultimately on force.

The third aim is to introduce you to some of the complex issues that are involved in interpreting works of art, with particular reference to Gros's best-known Napoleonic paintings. What makes it difficult to view Jaffa and Eylau as straightforwardly propagandist works is their depiction of suffering and death, which seems to evoke the costs rather than the benefits of Napoleon's rule. Rather than trying to account for the horrific elements in the paintings in terms of a hypothesis about the artist's intentions (that is, Gros's supposed doubts), we will relate them to the fundamental stresses and contradictions of the regime.