2.2 David Dale and New Lanark 1785–1800

Although New Lanark was not the first, it became one of the largest and most important cotton mills of its period. It was planned and developed near the Falls of Clyde in 1785 by David Dale (1739–1806) (see Figure 2), a prominent Glasgow merchant banker, and by Richard Arkwright (1732–92), who in the 1780s was actively promoting his patented water-frame both in Scotland and on the Continent. Arkwright soon abandoned his interest, leaving Dale and his managers to build New Lanark on a site feued (leased) from Lord Braxfield (1722–99), who had an estate nearby. (Incidentally, Braxfield, as Lord Justice Clerk, presided in 1793 at the trials of the leading Scottish Friends of the People, a group that advocated moderate parliamentary reform as a means of preserving the British constitution, including the Radical lawyer and great Scottish patriot Thomas Muir (1765–99).) The large mills, four in all, were constructed by the river's edge, and water to drive a series of massive wheels was diverted from the Clyde by tunnel and aqueduct. Beyond the mill complex Dale created a model industrial community with a planned village providing housing, school, kirk (or church) and other social facilities for its workers. What all this cost is unknown, but when Owen and his partners bought the place in 1799 they paid £60 000, said to be cheap at the price. So Dale's investment was substantial, making New Lanark one of the largest plants of its kind.

Exercise 1

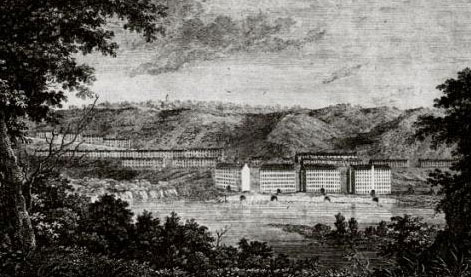

Examine Figure 3 above, the earliest representation of New Lanark, then view the introductory section of the video given below. Describe the location and layout of the mills and community.

Click play to view the introduction section of the video (Part 1, 11 minutes)

Transcript: Introduction - Part 1

Click play to view the introduction section of the video (Part 2, 11 minutes)

Transcript: Introduction - Part 2

Discussion

The mills are by the edge of the Clyde at a point where the head of water was at its optimum for driving the machinery. The mill races from four of the wheels can be seen in the engraving. Because of the constricted nature of the site the housing is ranged behind, some stretching uphill to the left and some (the earliest, we think) beyond the mills to the right.

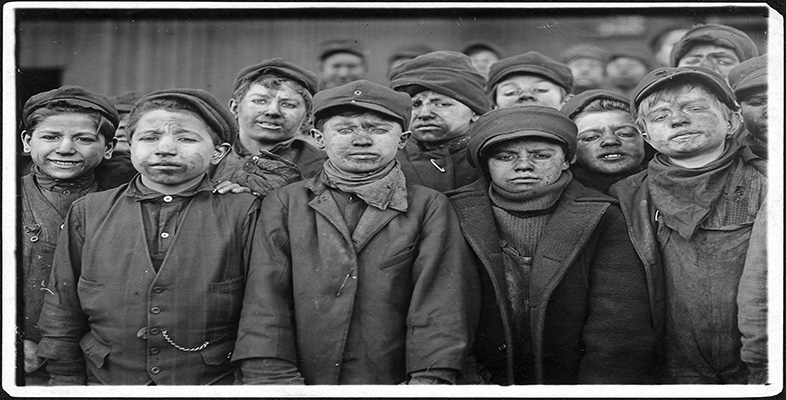

Apart from the costly technical and engineering difficulties involved in such a massive project, assembling a large and suitable labour force (initially perhaps comprising 1000 people) was a difficulty that Dale (and later Owen) shared with many other mill owners. Locals, perhaps understandably, seemed reluctant to seek employment for long hours in a place whose barrack-like appearance resembled a workhouse, and more widely people were said to be ‘averse to indoor labour’, meaning they did not seem to like the idea of working in ‘manufactories’, as they were called. Accordingly large families were recruited from other parts of Scotland and, as was the norm, both women and children were employed. In truth a large proportion of the labour force (maybe as much as half) were children, some being orphans apprenticed from the institutions or parishes of Glasgow and Edinburgh. The men worked as tradesmen or overseers, or, if they lacked skills, as labourers. There was also a distinctive and substantial cohort of Gaelic-speaking migrants from the Scottish Highlands, some of whom Dale had rescued from a storm-bound emigrant ship bound for North America, and others he had enticed to New Lanark from localities as far apart as Argyll or Caithness by offers of employment and housing.

By the early 1790s New Lanark, deep in its valley by the Clyde, had a densely packed population of about 2000, half of whom were either children or teenagers, the majority employed in the mills. Apart from assembling and training the labour force, the maintenance of time-discipline in the works and of order in the community must have presented major problems. Although an astute businessman, Dale was also a pious individual, head of a Dissenting Presbyterian sect, and his regime was reported as paternalist. By the standards of the time he and his resident managers provided decent working conditions and seem to have been particularly attentive to the accommodation, clothing, health and diet of the child apprentices (Donnachie and Hewitt, 1999, pp. 40–9).

Whoever inherited the community Dale had established would have a sound foundation on which to build, quite apart from the success of the business, by modern values probably a multimillion pound enterprise even before Owen and his Manchester partners assumed management. We shall learn more about the early history of New Lanark and view other features on the video later in the course. But for the moment this brief description of New Lanark highlights some of the major difficulties of industrialisation and the social problems the economic transformation engendered.

Exercise 2

Review the preceding section and identify some of the key problems that industrialisation seemed to generate.

Discussion

There were major architectural and engineering problems in building the new factories, but these were soluble with large amounts of capital investment (on which, with good management and luck, substantial returns were possible). Perhaps more acute were the difficulties of assembling, retaining and controlling a large labour force. This often involved in-migration to new localities, over quite long distances and from different linguistic, cultural and religious backgrounds (likely to generate tension in the new communities). Housing had to be constructed very quickly. High densities, rudimentary water supply and poor sanitation threatened health and promoted disease. Factory masters were also concerned about preventing immorality, drunkenness and crime among workers.

I would not have expected you to get all of this, or necessarily to put it all in the same order, but you can see that the growth of New Lanark and other factory communities brought many of the social changes – and problems – that accompanied industrialisation generally. There were already major concerns about a whole host of issues, including population growth, urbanisation, health and disease, crime and policing, children's employment, adult unemployment, poverty and popular education.

Anyone with the answers to these problems was certain to command attention from governments wrestling with the costs of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. These conflicts hit the pockets of the landowners and industrialists through taxation, even though some were profiting handsomely from improved agriculture and the new manufacturing. There were also worries, widespread among the middle and upper classes, about increasing poverty and social unrest. And, as with slavery, many if not all of these issues challenged the enlightened and humane, who believed in social progress.