4.4 Manchester Literary & Philosophical Society and Board of Health

In the meantime Owen joined the town's social and intellectual elite, which like its politics was largely dominated by Dissenters. They were prominent in the Manchester Literary & Philosophical Society which Owen joined in 1793. There he associated with some significant reformers, heard papers on a wide range of intellectual, industrial and social topics, and himself presented papers dealing with such issues, including one on education.

The society was founded in 1781, the co-founders being Thomas Percival, Thomas Barnes and Thomas Henry. These and other leading members, such as John Ferriar, president when Owen joined, and John Dalton, a chemist and physicist, were in their different ways true sons of the Enlightenment. Percival (1740–1804), a physician and reformer, studied medicine at Edinburgh, associating with Scottish Enlightenment figures like David Hume and William Robertson, later completing his studies at Leiden, the Dutch university famed for its medical teaching. Interested in social conditions and public health, he probably first met Owen when inspecting new sanitary arrangements in Drinkwater's factory. Barnes (1747–1810), a distinguished scholar and Unitarian minister at Manchester's Cross Street Chapel, which Owen evidently attended, was also an educational reformer. Henry (1734–1816), an apothecary and chemist, helped pioneer the teaching of science and medicine in Manchester. Although Dalton (1766–1844) achieved greater fame, Ferriar (1761–1815) was the most interesting of the leading figures in the society. A physician at the infirmary, he was also interested in public health and factory conditions. His Medical Histories and Reflections (1792–8) clearly linked the spread of disease to social conditions. He was interested in literature and philosophy too, publishing in 1798 a study of the novelist Laurence Sterne (whom Owen had evidently read as a youth). If Owen was to learn more about social reform he could hardly have chosen better company.

The society covered a wide range of subjects: literary, philosophical, scientific, medical and humanitarian. It also took a great interest in the town's staple industry. Indeed, the first paper Owen heard was on ‘The nature and culture of Persian cotton’, to which he responded at Percival's prompting. Soon after joining in November 1793 he was precocious enough to turn the knowledge he possessed of the town's main industry to good account, reading a paper entitled ‘Remarks on the improvement of the cotton trade’. This went well, generating some interesting discussion; Percival was encouraging, and complimented him on his paper.

Owen delivered a second paper on ‘The utility of learning’ a month after the first. The title of the third, given in March 1795, was ‘Thoughts on the connection between universal happiness and practical mechanics’, the fourth, read in January 1796, being ‘On the origin of opinions, with a view to the improvement of social virtues’. These contributions all had some relevance to his subsequent philosophy and social psychology, especially his emphasis on the influence of environment in shaping character. Unfortunately none of his papers was printed and this may indicate that they were little more than commonplace. However, it seems highly likely that Owen carried some of the more important ideas he was then contemplating into his later work (Donnachie, 2000, pp. 61–2).

He may well have been influenced by other lectures and discussions on public health and on the growing problem of the poor, especially in an urban-industrial context. On 13 December 1793 he heard a paper by James Percival, Dr Percival's son, on ‘A philosophic enquiry into the nature and causes of contagion’, while on 19 April 1794 Samuel Bardsley, another physician, who later gave evidence in support of Robert Peel the Elder's factory bill (which became the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, the first to promote better conditions for children employed in factories), spoke on ‘Party prejudice, moral and political’. On 1 April 1796 Bardsley addressed himself to ‘Cursory observations, moral and political, on the state of the poor and lower classes in society’, a subject of great concern to the authorities and one underpinning much of Owen's later views on society.

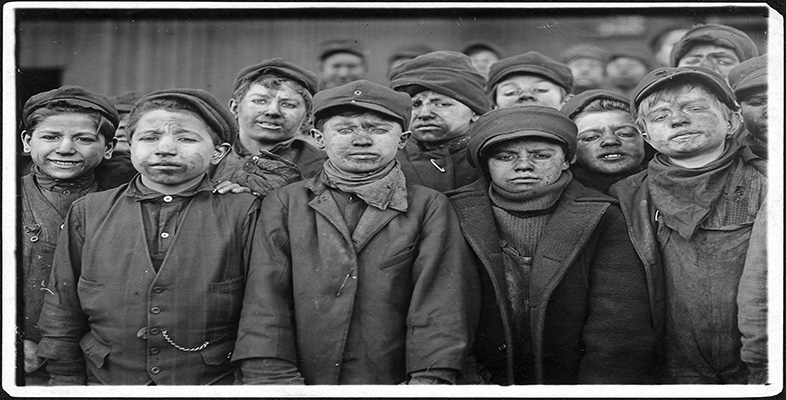

The reforming instincts of these individuals, including Owen, found expression in another important organisation, the Board of Health, established in 1796. Because of its interests in factory conditions, and in child labour in particular, its influence ranged far beyond Manchester. Anticipating the campaign that ultimately led to Peel's bill, it gathered evidence from masters about the treatment and condition of apprentices in their mills. The Board solicited information on prevailing conditions from far and wide, Dale being one who responded in detail to its questionnaire. It is an interesting speculation that Owen might have learned for the first time about the regime at New Lanark when he scrutinised Dale's replies to questions about the treatment of his apprentices. Moreover, Owen perhaps already knew about the large Scottish mills, including Dale's. He could have read about them in the early volumes of Sir John Sinclair's Statistical Account of Scotland (1791–9), a major text of the Scottish Enlightenment, possessed by libraries like that of the Manchester society.

Exercise 5

Can you suggest what impact on Owen's intellectual development and ideas his participation in the Manchester Literary & Philosophical Society and the Board of Health might have had?

Discussion

First, he had the opportunity to extend his education through discussion, debate, reading Enlightenment thinkers and associating with other members. Second, his involvement helped formulate his own ideas about education and its role in society. Third, he gained an awareness of wider social issues, such as health and welfare, in and beyond the workplace.

Owen's activities on behalf of the Chorlton Twist Company involved travelling to see customers in Scotland, and it was during one of his visits to Glasgow, probably in 1797 or 1798, that he met Dale and inspected New Lanark for the first time. He was evidently impressed and given his knowledge of the industry could see that with better management it might prove highly profitable. He says that he also recognised its potential as a test-bed for his social ideas, but this may have been hindsight after the event (Owen, 1971, p. 46).

On subsequent visits he not only met Caroline, Dale's eldest daughter, but discovered that her father was anxious to dispose of some of his assets, including New Lanark. By 1799 Owen had negotiated the sale of the mills to his company on highly favourable terms, installed himself as managing partner, and married Caroline into the bargain. Although previously successful and financially secure Owen, as effective business heir and adviser to the now ailing Dale, was likely to rise still further and prosper greatly. As in Manchester Owen joined the Glasgow elite, identifying himself with social reform and associating with Scottish Enlightenment figures in the university and intellectual society of the city.