2 The Enlightenment and its mission

2.1 Definitions

‘The Enlightenment’ is used to refer:

to a chronological period (roughly, the middle and late decades of the eighteenth century between around 1740 and 1780), often also called ‘The Age of Reason’; and

to the unprecedented focus on a particular set of values, attitudes and beliefs shared by prominent writers, artists and thinkers of that period.

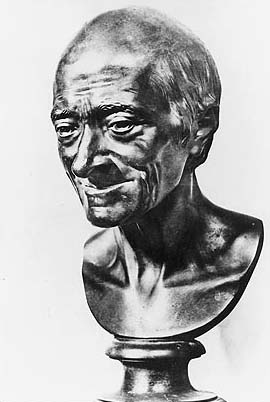

There were changes of emphasis depending on date: it is common to distinguish, for example, between early and late Enlightenment attitudes, while the half-century beginning around 1680 is often thought of as the pre-Enlightenment. There were also different ‘varieties’ of Enlightenment depending on national, social and political contexts. The sweep of the Enlightenment was enormous: from Lisbon to Saint Petersburg and from Edinburgh to Naples. Enlightenment culture spread from one nation to another, defining a pan-European consciousness of tremendous force. Each nation added its own dimension. In France, for example, there was a much greater sense of opposition to the (Catholic) Church than in England, where the religious establishment was perceived to be far less oppressive. It is agreed that the Enlightenment was at the height of its influence in the 1760s and early 1770s. Of its most representative figures in France, Voltaire died in 1778 and Diderot in 1784 (see Figures 1 and 2). There is also a consensus that certain key attitudes characterise what we may describe as an Enlightenment outlook.

The Enlightenment consisted, in essence, of the belief that the expansion of knowledge, the application of reason, and dedication to scientific method would result in the greater progress and happiness of humankind. The Enlightenment outlook was buoyant, reformist and humanitarian. The archetypal Enlightenment thinker was confident that the world is ultimately both rational and beneficent, that nature, including humanity, is essentially good or at least not innately depraved, and that people have the potential to improve themselves and their environment and to make the world a better place.

Among the factors that gave particular credibility to this belief one ranks high: the epoch-making discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727) at the end of the seventeenth century regarding the motion of the planets and gravitational force. Newton's achievements had a profound and lasting impact that spread far beyond the sphere of physics. They suggested that the natural world could be explored and understood, and that nature and everything in it was governed by underlying ‘laws’; that there were rational, universally valid answers to the questions asked by an enquiring mind; that for every effect there was an identifiable cause, for every natural phenomenon an explanation, a category and a definition, if only we try hard enough to find it. This confidence in reason or intellect lies at the heart of the Enlightenment.