8.4 The Enlightenment and modernity

In its desire to replace outmoded, irrational ways of thinking by the rational, the sensible and the progressive, the Enlightenment was self-consciously modern. A manifestly scientific age and the visible advancement of knowledge in the eighteenth century required, it was felt, an overhaul – or at least a careful critical and radical scrutiny – of culture, society and their institutions. This was the implicit message of the Encyclopédie. Its contributors were convinced that they were motivated by feelings of beneficent humanity, that they were on the side of the future and that the future was on their side. In spite of its allegiance to the classical tradition, the Enlightenment was a modernising force, keen to review and regenerate culture and society. The classics themselves were often used as authorities to support change. When Diderot argued in the Encyclopédie article ‘Epicureanism’ for a moral code that legitimised the pursuit of pleasure, he appealed to the authority of the ancient philosopher Epicurus. Napoleon was described by Stendhal as ‘imbued with Roman ideas’ (Stendhal, 2004, p. 53), though the Roman style and emblems of his rule moved rapidly from republican to imperial. When William Gilpin set out his new aesthetic of the picturesque, he cited the poets Ovid and Virgil to exemplify the evocative landscape effects he sought in art. Excavations of ancient sites such as Pompeii and Herculaneum and new scholarship on antiquity brought fresh models and inspiration to architects and their patrons. Architects such as Soane invigorated their architecture by drawing on such scholarship. More broadly, the Enlightenment's mission of rational scrutiny and reform opened the way for changes of attitude and values among the educated sections of society. Diderot described the purpose of the Encyclopédie as being ‘to change people's way of thinking’. As we have seen, moral codes were secularized; deism was promoted as a more rational, acceptable version of religion. Authority of all kinds – monarchical and ecclesiastical as well as noble privilege – was challenged. These changes were accelerated and converted to action in France by the Revolution, which swept away within a few years what it called the Old Regime, the old social and political order and the privileges of nobles and clergy.

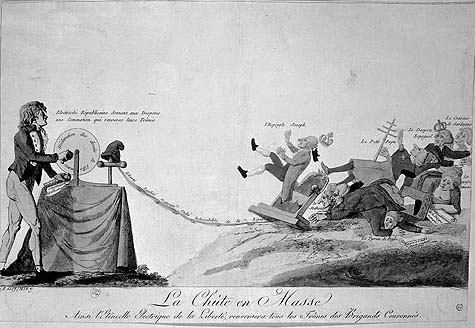

In 1790 the French first adopted a form of constitutional monarchy on the British model, guided and restricted by a legislative assembly representative of a wider, though by no means completely inclusive, constituency. Respect for noble birth was replaced by respect for men of property regardless of their lineage. The relatively moderate reforms of the early years of the Revolution then gave way to more violent upheavals, as resentment stirred against the new aristocracy of the rich. The monarchy was replaced by a republic (see Figure 15), which in turn, under pressure of war and civil war, soon fell under the sway of a ruthless dictatorship. When the violence had abated and political power was once more restored to a property-owning elite, there was scope for a large new meritocracy with equal citizenship and equal treatment before the law. While under the Old Regime no one had been admitted to the French court since 1760 unless he could trace his noble ancestry back to the fourteenth century, Napoleon's declared maxim was la carriere ouverte aux talents (careers open to talent). His claim that every foot-soldier carried in his knapsack the baton of a marshal of France was not literally true; nevertheless his marshals and administrators included men of humble origin brought to positions of authority by the needs of the Revolution and the Napoleonic empire, and even raised to Napoleon's imperial nobility. These were spectacular changes on an unprecedented scale. When Napoleon rose to power, the changes were seen as gleaming signs of France's modernity, a model to be imposed on the rest of Europe. Napoleon could be seen as the ‘son of the Revolution’ who guaranteed its positive achievements while protecting its beneficiaries from the former anarchy and violence of the urban crowd.

Napoleon's image as ‘son of the Revolution’, restorer of order, product of the Enlightenment, bearer of civilisation and ‘great man’ often masked a brutal political cynicism. The painting by the French artist Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835), Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken of Jaffa (1804), shows Napoleon as compassionate hero when he had in fact just authorised a number of violent atrocities during the Egyptian campaign. From the first, he suppressed freedom of expression and the press, reintroduced slavery in the French colonies, and came to be seen by many as another brand of tyrant. But it was some years before Europe lost faith in the positive, modernising energy he seemed to represent, and after his fall he was missed as a vigorous, inspiring and enlightened alternative to the reactionary restored Bourbon monarchy. Spain, attached to its Catholic and social traditions, resisted his modernity as it fought his invading armies, and Napoleon's imperial ambition to complete his domination over the whole of Europe stimulated national self-consciousness as a counteracting force in Spain, Russia and Germany.

Another modernising force in the period covered by the course was the growing pace of industrialisation, as the methods of cottage outworkers were gradually replaced by mass factory production of goods. As people moved increasingly to work in towns, old social communities and values were under threat, and it was in such a climate that Evangelical Christianity began to thrive. The concept of ‘modernity’ is often associated with the secular, rational and progressive aspects of the Enlightenment, more specifically with the growing status of secular public opinion (Porter, 2000, p. 23). The process of ‘modernising’ permeated culture in all kinds of ways, however, and was certainly not restricted to the secular. Evangelicals defined a new kind of faith in response to growing concerns about the ability of traditional Anglicanism to meet the needs of a swiftly changing society. The poet William Cowper and the Evangelical Christian John Newton collaborated on the production of new hymns for the parish of Olney. Together with the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce, they turned their backs on the growing pursuit of material prosperity that came with industrialisation in order to define more exacting or rewarding routes to salvation. Reacting against what he saw as a detrimental decline in faith, Wilberforce proposed an alternative, spiritually inspired modernity in the form of a religion that built on personal experience while rejecting superstition. The modernising forces of the Enlightenment could, then, take the form of regeneration rather than the violent break with tradition produced by the Revolution.

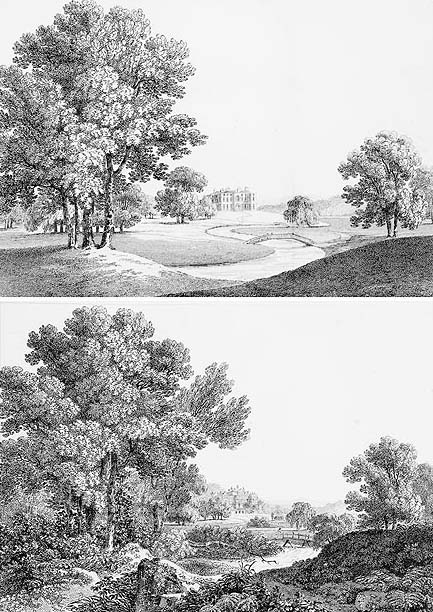

The modernity of the Enlightenment also had aesthetic consequences. Whig landowners in Britain wishing to assert their independence from conservative royalist politics ‘modernised’ the landscape by sweeping away rambling, picturesque gardens associated with nostalgia and replacing them with the extensive lawns and artificial water courses made fashionable by the landscape designer Capability Brown (see Figure 16). They built obtrusive, gleaming white Palladian mansions in a grand classical style in dominating positions within ‘wild’ landscapes such as the Lake District in order to assert their modern taste and their will for change. And yet such impulses towards modernity did not remain unchallenged. The Enlightenment's own respect for nature stimulated lively debate among thinkers such as William Wordsworth, Uvedale Price and William Gilpin about the extent to which art and artifice should alter the natural appearance of the landscape. The scene was set for a man versus nature dialectic that would lie at the heart of Romantic concerns.

Summary point: the Enlightenment was characterised by an impulse towards modernity in matters of government, politics, religion and aesthetics. There were those, however, who questioned the rapid momentum and effects of change.