3.3 The reasons for – and emergence of – women working in medicine

Why in the face of such resistance did women wish to become doctors at all? Until recently, many authors have argued that women pursued a medical career as a form of service and for altruistic reasons. Women doctors claimed to be serving the public (one of the features of a profession) by preserving the modesty of women patients and ending their suffering at the hands of male doctors who did not understand the female body. This idea of women being called to serve for the betterment of others is a common feature of many autobiographies written by pioneer women doctors and contemporary biographies. However, recent scholarship suggests that women may have constructed narratives of their lives in ways that would be acceptable to society.

Given the obstacles that had to be faced, the fact that women doctors often told their stories in terms of having received a calling, or having been possessed by a mission is scarcely surprising. To have felt possessed by forces outside one's own control was probably easier than owning up to one's own driving ambition.

(Dyhouse, 1998, p. 324)

Exercise 3

Read ‘Motives for medical training [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ’. According to this account, what motivated Mary Murdoch to qualify as a doctor?

Discussion

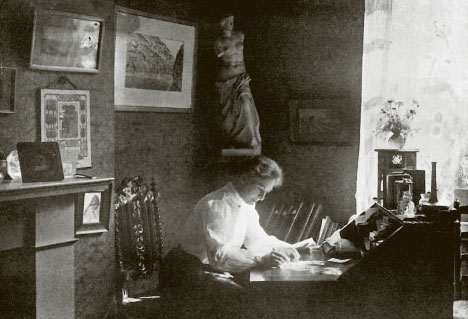

This account suggests that Mary Murdoch (1864–1916) (Figure 3) was bored by the life of a ‘lady of leisure’ and did not want to waste her years in the ‘small activities’ of a country town. As the only daughter left at home, she cared for her mother until her death and was then left with the problem of how to support herself. With a small legacy and no husband she had to find a career. The family physician clearly had some influence. Thus her career choice might have resulted from changes in her family life and from a desire for freedom.

In the second passage, Murdoch is shown as offering herself to medicine in a way similar to that of a noviciate offering herself to God. Murdoch was a deeply religious woman, and her Catholicism seeps through the piece as she justifies her choice of career. Her medical career is presented as a life of self-sacrifice. While loving her chosen profession, Murdoch presents it as a life of service and devotion to the detriment of other pleasures, as medicine has taken away her liberty.

Murdoch's biography hints at the role played by male supporters in encouraging women in their chosen path. While women did face fierce opposition, mainly from elite practitioners who made up the staff of the largest medical schools and teaching hospitals, they also received help and advice from individual men. At Edinburgh, for example, Jex-Blake had invaluable support from two men. Alexander Russel was editor of the Scotsman newspaper and did much to publicise the unfair treatment meted out to the female medical students. David Masson was professor of English at Edinburgh University, and a strong supporter of education for women.

Having been denied access to established medical schools, some British women were determined to found their own training courses. This was quite possible in Britain where there were many private medical schools set up by practitioners. Opinion was divided on the matter among medical women. Garrett Anderson and Blackwell opposed the idea of a separate education for women, fearing that it would be regarded as inferior to that received by men. After she failed to graduate from Edinburgh, Jex-Blake moved to London in 1874 and began to plan a women's medical school. The London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW) was opened in October 1874 and received the support of some men, including the Earl of Shaftesbury, and some intellectual radicals, including lawyers (for example, William Shaen, who acted as solicitor to the school) and politicians (for example, James Stansfeld, who supported women's suffrage). The LSMW did not provide a way into medicine for all women: the founders limited admission to the very brightest and charged high fees of £200 per annum. Lectures were given by male and female doctors already in hospital posts and, from 1877, the female students were able to gain clinical experience at the Royal Free Hospital (Blake, 1990, p. 186). While the LSMW offered opportunities for education to women when other routes to medicine were blocked, it did not provide the same springboard to a medical career as a ‘male’ education could do. Its staff did not belong to the medical elite and could not offer their graduates entry to junior posts in prestigious hospitals. Without support from distinguished hospital staff when seeking posts, many of the LSMW's students worked in lowly positions within the medical hierarchy – as medical missionaries for instance.