3.4 War and women in medicine

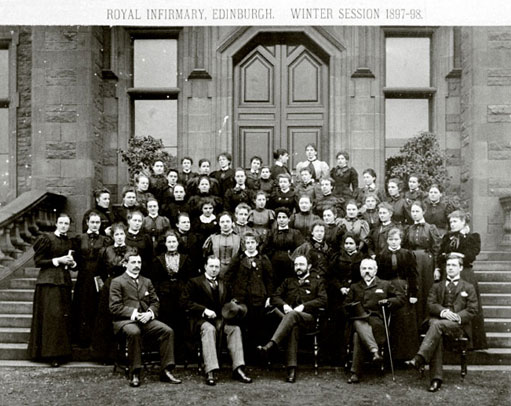

Until 1914, the number of women attending medical schools grew slowly (Figure 4). In Britain, even after the 1876 Enabling Act allowed medical examining boards to grant licences to women, universities could still legally exclude women from their medical schools. By 1881, there were only twenty-five women doctors in England and Wales – a total of 0.17 per cent of the profession. By 1911, there were 495 women on the register, comprising just under 2 per cent of the profession (Harrison, 1981, p.51). In Germany, there were only a total of 138 women physicians in the entire Reich by 1913. It was in Russia that female medical students were the most numerous. By the First World War more than 1,600 had qualified and were practising – more than the combined number of qualified women throughout the rest of Europe (Bonner, 1992, p.78).

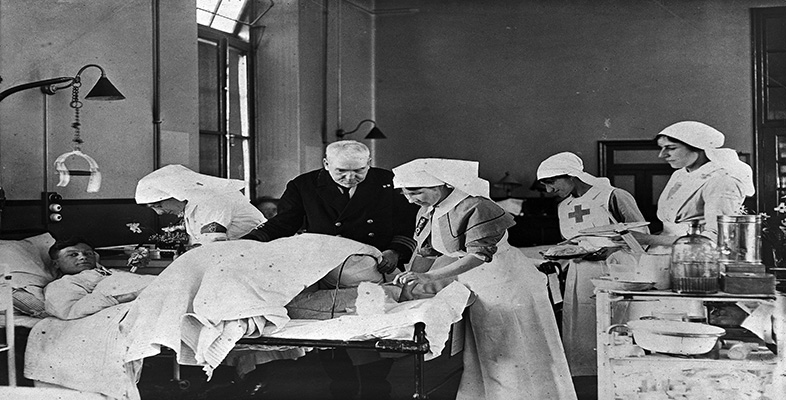

The First World War is often portrayed as a watershed for women, opening up many new employment opportunities. The war certainly gave medical schools an incentive to open their doors to women, as the number of male applicants fell and the call up of male doctors offered increased opportunities for women to practise on the home front. Some women were able to work close to the battlefield itself, in the Scottish Women's Hospitals (SWH). Funded through charitable donations, the SWH saw service under French command (the British Army refused the services of the women) on the western front and in Serbia. However, the idea that the war irrevocably improved the situation for women wishing to pursue a career in medicine is overstated.

Many medical schools persisted in their opposition to women, and, at the end of the war, limits were once again put in place.

One by one the London teaching hospitals again closed their doors to female students. University and King's College Hospitals retained limited places, but otherwise the Royal Free was the only London hospital offering them clinical induction.

(Leneman, 1994, p.176)

At St Mary's Hospital Medical School in London (which had supported the admission of women from 1916), male students and staff started to complain about the female students. The arguments reached a crisis point in April 1924, when ninety-six male students signed a petition for the removal of the female students (Garner, 1998, p.83). The hospital discussed the matter and decided that from 1925 no more women would be admitted. Although St Mary's chose to exclude women, in other medical schools the backlash against female students was dying away. The number of women studying in British medical schools increased during the late 1920s and 1930s. By 1931, there were 3,331 qualified women, accounting for about 10 per cent of the medical profession (Cherry, 1996, p.33). This was not the case throughout Europe, however. In Germany, for instance, the proportion of women in medical schools actually fell by 17 per cent between 1923 and 1928 (Bonner, 1992, pp.162–5).

The inter-war period was also characterised by gains and setbacks in the career paths of individual women. Male practitioners were still able to push women into the margins of the profession – just as they had marginalised practitioners who practised unorthodox forms of medicine – by denying them access to research opportunities and prestigious posts. For some, such as Mary Walker (1888–1974), barriers remained to their career progression. Walker spent much of her career working in London Poor Law hospitals (regarded by most practitioners as a low-status post) despite a clear aptitude for research. Her doctoral thesis won the Edinburgh Gold Medal in 1937, but she did not take up the offered post at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital to pursue research in neurology. Whether this was a consequence of male opposition, lack of desire or the impact of marriage and a family is unclear. Others, such as Letitia Fairfield (1885–1978), were able to have careers which mirrored those of their male colleagues. From an intellectual family (her sister was the novelist Rebecca West), Fairfield took a post with the London County Council in 1911, and eventually became its first female senior medical officer. She served in a medical capacity in both world wars and had interests in maternal, child and geriatric medicine (Hall, 1994, pp.194–5).

Women's access to the medical profession was thus fraught with difficulties, which even by the 1920s were not completely removed. As Porter has noted, women faced two obstacles to entry into the medical profession: first, medicine was a ‘chummy male monopoly’ (1999, p.356) and second, it required a university education which was largely denied to women. Biological arguments about women's suitability for medical work were utilised in specific ways to maintain and protect existing professional structures and to prevent equal access and progression for women well into the inter-war years.