3.5 The health of mothers and children

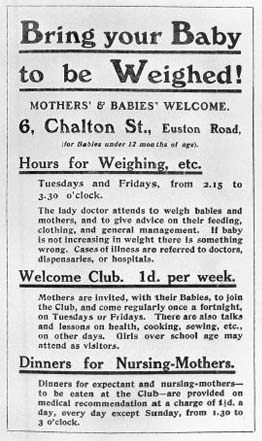

The health of mothers and infants was one target for action. France was among the first to introduce infant welfare schemes, as low birth rates, high infant mortality and defeat in the Franco-Prussian War led politicians to fear for the future strength of the nation. Diarrhoea among bottle-fed babies was singled out as a preventable cause of high infant mortality. From the 1890s, charities and local authorities set up infant welfare clinics called gouttes de lait, which encouraged mothers to breastfeed, gave out free milk to those that could not, and provided free regular medical examinations to check on babies’ development. Charities also provided free meals to pregnant women and the mothers of small children. To improve the health of older children, municipal authorities set up school canteens to provide free and subsidised meals. These schemes proved very popular: in Paris in 1901, over 1,400 babies were brought to clinics: in some towns, up to one-third of all mothers and infants attended. Government bodies in Britain looked to France as a model of good practice, but did not simply copy French child welfare programmes, fearing that to provide food would usurp the role of the family breadwinner and overstep the proper limits of action. Hence, the few ‘milk banks’ set up in Britain around 1900 offered subsidised rather than free milk. Instead, charities focused their efforts on education. Lectures and demonstrations on ‘mothercraft’ were offered at welfare centres (Figure 4). In Britain, efforts to provide free school meals for older children were hindered by the same reluctance to interfere in family life. Even after they were given powers to provide school meals in 1906, many local authorities were reluctant to do so and, by 1912, only around one-third of local authorities provided school meals (Dwork, 1987, pp. 93–166, 167–84).

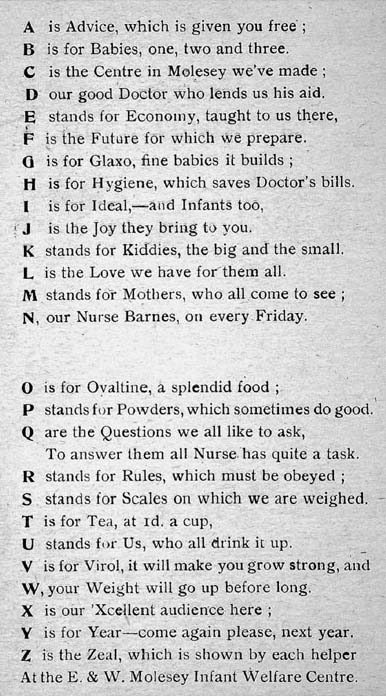

Historians are divided over the impact of such policies. Some have argued that the authorities in Britain chose to provide education, rather than food, as a cheap but ineffective solution to the problem of child poverty. They have portrayed education in ‘mothercraft’ as patronising and often impractical. Other researchers, such as Deborah Dwork, are more sympathetic, arguing that, given the government's reluctance to interfere in the family, education was a practical and effective way of helping mothers, and one which the mothers themselves appear to have found useful (Figure 5).

Governments also provided working-class children with access to physical exercise (PE) through school. Again, wider politics dictated the level of provision. By the 1930s, schoolchildren in Germany, Czechoslovakia, Russia and Italy were taught games, drill and gymnastic exercises. These facilities were much admired by British government ministers (although they did not approve of the regimes that funded them), who attempted to establish PE as a regular part of the school curriculum. Exercise was presented as a cheap form of preventive medicine, which would help to prevent ‘flat-feet, curvature of the spine, adenoids, deafness, “mental deficiency” and respiratory problems’ (quoted in Welshman, 1996, p. 34). However, in Britain, local authorities were again slow to act, and provision of PE was patchy in the state school system. Hampered by a lack of trained instructors, and the fact that many children could not afford appropriate clothing and shoes, the periods of exercise were shorter and less frequent than those provided in private schools.

Education in hygiene was provided by both charities and local government. In Salford, before the First World War:

The Ladies' Health Society worked bravely among us … Together with the ‘Sanitary Society’, they visited the ‘lowest classes’ and found ‘much that is saddening: but there are bright spots – clean homes, pretty little sitting-room kitchens … clean hearths, chests of highly polished mahogany drawers, a steady husband, a tidy wife and children’ … The Society also sold ten hundredweights of carbolic soap and distributed six hundredweights of carbolic powder [disinfectant] … The corporation lent out its whitewash brushes, distributed free, bags of lime and bottles of a preventive medicine popularly known as ‘diarrhoea mixture’, and urged hygiene on all the populace.

(Roberts, 1971, pp. 57–8)

Children were taught basic hygiene – about the need to bath weekly, to wash their hands and faces daily, and to scrub their fingernails – as part of the school curriculum. Girls (but not boys) were taught about healthy clothing – garments should be loose, warm and frequently washed.