5.2 General practitioners

General practitioners were the backbone of medical services. They dealt with almost every sort of complaint, from the serious to the trivial. Although it is often assumed that previous generations were prepared to put up with discomfort, in 1876, an anonymous correspondent to a friendly society magazine complained that ‘one of the most distinctive traits of this generation is its almost fidgety care about its health’ (quoted in Riley, 1997, p. 199). Working men went to the doctor with minor injuries, colds and headaches. One Yorkshire doctor recorded treating a patient for indigestion, toothache, hoarseness and hair loss (Riley, 1997, pp. 199–200). At the other end of the scale, GPs delivered babies in patients' homes, even applying anaesthetics and using forceps to speed the delivery. In rural areas, they performed major surgery. Harry Pearson Taylor, a GP on the Shetland Isles, recalled amputating a boy's arm after it had been crushed in a threshing machine. With the minister of the local church, he

improvised an operation table, and got the little man on it. I disinfected the area as well as I could under the circumstances, and got all I wanted ready. I chloroformed the boy, and the Minister kept him under while I disarticulated the elbow joint. The Minister, who … knew quite a lot about medicine and surgery, had put a tourniquet on the upper arm. The weather remained so bad for several days that I was storm stayed in the island, which gave me an opportunity to attend to the patient myself. Of course there were no nurses in those far back days, and had I been able to get back to Yell [his home island], the Minister would have had to undertake the duties of a nurse.

(Taylor, 1948, p. 76)

Despite the primitive conditions of his treatment, the child made a full recovery. However, the bulk of a general practitioner's work was more mundane. GPs prescribed medicines for a range of illnesses, treated injuries and local infections, lanced boils and syringed ears.

Middle- and upper-class patients paid directly for care from general practitioners, but they did not all pay the same fees. GPs charged according to the patient's income. In 1917, the Ladies Diary and Housekeeper provided a table of charges, based on the rental value of homes, suggesting that GPs would charge from 2s 6d to 10s 6d for a visit, and from 1 to 5 guineas for a midwifery case. By the early twentieth century, some medical practitioners built successful practices among the upper working classes, by lowering their fees to as little as 1s or even 6d – a price that put their services within reach of many working-class patients (Digby, 1999, pp. 100–3).

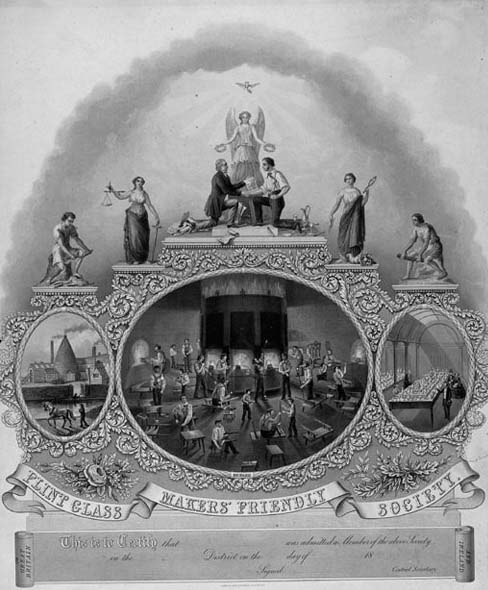

In the late nineteenth century, working-class men began to obtain access to general practitioners through insurance schemes. In Britain, these schemes were run by friendly societies or sick clubs (Figure 7), in France, they were called sociétés de secours mutuels (mutual aid societies) and in Germany, Krankenkassen (literally a ‘sick box’). All worked on the same principle: for a small weekly payment, workers were entitled to financial help when ill, and had access to treatment from the society's doctor. A substantial portion of the male working population had some form of insurance cover. In Britain, friendly society membership peaked in 1900, when around half of the entire adult male population was insured. In France in 1902, over two million people belonged to some form of insurance scheme (Mitchell, 1991, p. 181). However, working women and the families of workers were often excluded from many of these schemes, and thus were less likely to go to a GP. In the twentieth century, state health insurance schemes gradually replaced the direct provision of medical care to the poor. Health insurance was set up in Germany in 1883, and in Britain in 1911 under the National Health Insurance Act. These schemes, which initially covered only the poorest workers, operated in the same way as private insurance, except that the workers' contributions were augmented by contributions from his employer and the state.

The combination of low fees and private and state health insurance produced a huge expansion in the number of patients who consulted a general practitioner. In Britain, the number of GPs doubled between 1860 and 1914, while the number of patients attending each practitioner remained roughly constant (Hardy, 2001, p. 17). However, not everyone was equally well provided with care. Even in the twentieth century, patients in remote Scottish islands faced a journey of several hours to consult a doctor. The situation was much worse in the eastern regions of Russia, where in 1913 the ratio of licensed practitioners to population was less than 1 in 10,000 (Hyde, 1974, p. 18).

While more people gained access to GP services in the first decades of the century, not everyone received the same quality of treatment. Patients who paid a higher fee received a better quality of care. General practitioners would call on wealthier patients in their homes, discuss the case, and offer advice as well as therapy (Figure 8). Better-off patients were more likely to receive a thorough physical examination, using diagnostic instruments. They were also more likely to have specimens sent for laboratory tests, and to receive new treatments, such as vaccine therapy or insulin for diabetes. They also benefited from referral to specialists for further diagnosis or treatment (Digby, 1999, p. 200).

Well-off patients could afford to employ several practitioners if they were unhappy with the treatment offered by their original doctor. However, this was a mixed blessing, if the doctors disagreed. For example, when Sir Leslie Stephen fell ill in 1902, he was initially attended by the family practitioner, Dr Seton. The family then called in Sir Frederick Treves, a distinguished surgeon, to give another opinion. Seton thought Sir Leslie was improving, Treves thought that he was seriously ill and required an operation. The family accepted Seton's view, and he remained in charge of the case until the autumn of 1903, when another surgeon, Hugh Rigby, was called in. He brought in a GP (Dr Wilson) to visit every day. The efforts of all these medical men had little effect – Sir Leslie died in February 1904 (Trombley, 1981, pp. 77–80).

Patients paying the lowest fees or receiving care through an insurance scheme received a much more basic consultation. In the next reading, Anne Digby examines state-funded care provided through the National Health Insurance Act of 1911.

Activity 2

Read ‘Services under the National Health Insurance Act’. In her view, did the National Health Insurance scheme provide good-quality care to all? Were both patients and doctors satisfied with the quality of the service?

Click to view the article 'Services under the National Health Insurance Act [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] '.

Answer

Digby makes clear that ‘panel’ patients received a lower-quality service in virtually every aspect of care than did private patients – including the surgery accommodation, the range of medicines prescribed, the length of consultation and the quality of the dressings. However, patients seemed happy with the service – relatively few of them changed their doctor or complained about the care they received. Digby suggests, however, that this may have been because they had low expectations of a service that they saw as similar to that provided by earlier sick clubs. Despite the long hours and heavy workload, doctors also seemed reasonably happy working under the National Health Insurance scheme, which provided them with a guaranteed income. However, she also notes instances of doctors not accepting that panel patients should receive poor care: for example, some were accused of ‘over-prescribing’ (i.e. not conforming to the expected standard of prescribing) and others complained about the use of poorer-quality bandages for their panel patients.

Digby's account may give the impression that patients were powerless in the face of a form of rationing of care, imposed by government and the medical profession. In fact, they exerted control over how they used the National Health Insurance system. Some commentators complained that patients abused the system by going to see their doctor for no good reason (Figure 9). Although doctors might appear to be ‘fobbing off’ their patients with stock medicines, in fact practitioners complained that patients expected to leave the surgery with a bottle of medicine (most drugs were dispensed in liquid rather than tablet form in this period). They were therefore forced to act in response to patient demand. Some of these frequently prescribed medicines had little pretensions to do any good. Elsewhere in her book, Digby reports that one doctor handed out coloured aspirins. In another practice, one of the stock medicines ‘was labelled “Mist. ADT” or “Mist. Any Damn Thing” [‘Mist.’ is an abbreviation of the Latin word for ‘mixture’ ] which was given to “somebody you thought there was nothing wrong with, and you could do nothing for”’ (Digby, 1999, p. 198). More alarmingly, another practitioner

prescribed a mixture … called Mist. Explo. It was a clear yellow liquid made from a few bright yellow crystals dissolved in water. The crystals were apt to ignite if left to dry in the sunlight, hence the name Mist Explosive. I don't remember the exact chemistry of this wonder drug but it was a derivative of picric acid and quite harmless when well diluted and used as a bitter tonic.

(Porter, 1999, p. 196)

Such medicines seem little different to patent medicines, which doctors so frequently condemned.