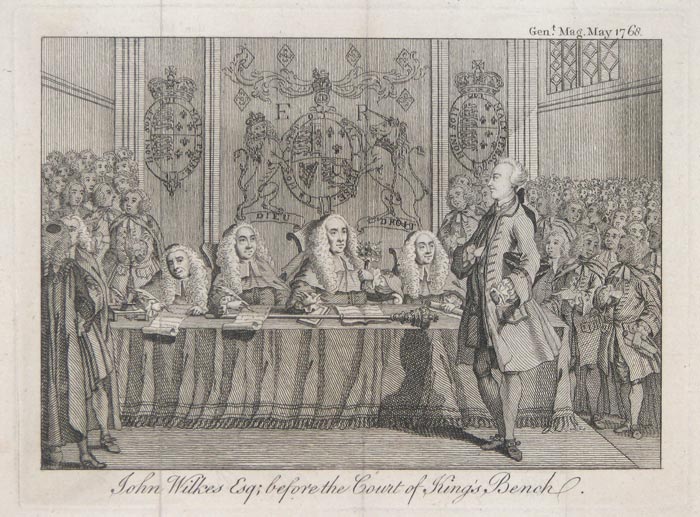

John Wilkes Esq; before the Court of King's Bench, engraving from The Gentleman's Magazine for May 1768.

John Wilkes Esq; before the Court of King's Bench, engraving from The Gentleman's Magazine for May 1768.

During the run-up to the 2017 General Election, we're dipping into the archives to bring you a collection of events from elections past - noteworthy, amusing or just plain bemusing. You can catch up on the 2017 election in our dedicated hub.

Another election for Middlesex occurred in 1769, vice Wilkes; the results were that Wilkes was returned at the head of the poll, while his opponent (with a quarter of his votes) was declared duly elected. On the subject of Colonel Luttrell’s admission to the House much was said which must have been unpalatable to the Court.

The Oxford Magazine printed a list of those members who were so patriotically inclined as to resist this brazen violation of the constitution, as “the Minority who voted 1148 in preference to 296;” while those members who servilely voted for the right of the ministers to impose a defeated candidate on the Commons were described as “the Majority who preferred 296 to 1143.”

A list is given of these placemen, pensioners, and courtiers, with particulars against their respective names which account for their lack of principle, all being in receipt of State patronage, or emolument of one kind or another, sufficient to prove that self-interest was their guiding principle, and that their consciences were closed by the greed of preferment. The despotic action enforced by the administration, in defiance of the principles of the constitution,—a common practice in the reign of George III.,—provoked a very pertinent disquisition upon the potentiality of the bulwark of popular rights.

The great Lord Bacon, somewhere talking of the power of parliaments, says, there is nothing which a parliament cannot do; and he had reason. A parliament can revive 191or abrogate old laws, and make new ones; settle the succession to the Crown; impose taxes; establish forms of religion; naturalize foreigners; dissolve marriages; legitimate bastards; attaint a man of treason, etc.

Lord Bolingbroke, indeed, is of a different opinion, and affirms there is something which a parliament cannot do: it cannot annul the constitution; and that if it should attempt to annul the constitution, the whole body of the people would have a right to resist it. It is natural, too, to think that Lord Bacon limited the power of parliament, great as he believed it, to those things which do not imply a physical impossibility. Modern ministers, however, have shown that a parliament is able, at least in appearance, to effect even such impossibilities.

Sir Robert Walpole was wont to boast that he had “trained his fellows,” as he called his venal majority in the House of Commons, “in such a manner, and brought them to such exact discipline, that were he to desire them to vote Jesus Christ a Gildon” (i.e. the head of an infidel sect, Gildon being a deistical writer in Walpole’s day) “he was sure of their compliance.” The ministry then in office (the Grafton administration), as will appear by the list referred to above, had assumed a power no less arbitrary and equally unreasonable, by persuading their servile majority to vote in defiance of the constitution on the question of Colonel Luttrell’s qualifications to sit in the Commons—that the 296 suffrages (recorded for Luttrell) were preferable to the 1143 polled for Wilkes.

As recorded by Joseph Grego in A History of Parliamentary Elections and Electioneering In The Old Days, published in 1886

John Wilkes would go on to present the first petition to Parliament calling for reform, in 1776.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews