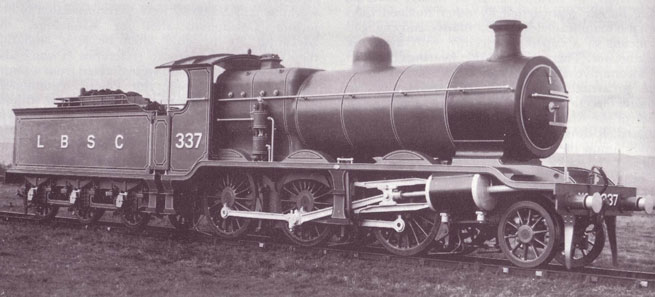

A later train in LBSCR livery

A later train in LBSCR livery

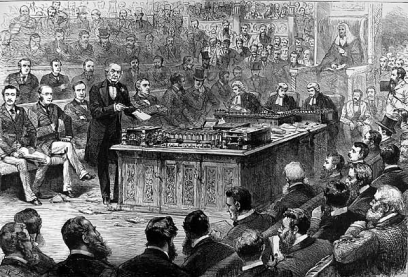

Fatal collision on the London And Brighton Railway

Last night an inquest was held by Mr W Payne, the coroner, and a numerous jury, at Guy's Hospital, on the body of William Jenner, who died at that institution from injuries received by an collision on the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, on the 27th of August last.

Captain Barlow, superintendent of the South-Eastern Railway; Mr Church, solicitor; Mr Biggs, manager; Mr Farmer, deputy-manager of the London and Brighton Railway; and Mr Faithful, solicitor, with several other officials, were in attendance during the inquiry.

Joseph Boardman was the first witness called. He said that he was an engine driver on the London and Brighton railway. He knew the deceased, who was his fireman. On the 27th of August, at about a quarter before five o'clock in the afternoon, their engine was at Coldblow, near New Cross. They were coming from Deptford-wharf on a branch line. They had started from Deptford-wharf at about twenty minutes to five, with a train of coal and stone. They had proceeded about half a mile when they saw a danger signal towards New Cross, on the side next to Greenwich Railways. When he saw that, he opened the whistle of his engine, and shut off the steam. Shortly afterwards the distance signal was turned, signifying that it was all right, and he went on.

Having passed that signal, he went on to the bridge, where he saw a man with the "all right" signal in his hand.

Having proceeded under the Brighton Railway, a man came out giving the signal to stop, but they were then going at the rate of fifteen or sixteen miles an hour. This man gave the signal with his hand. Upon this he shut off the steam, opened the whistle, and told the fireman to put on the break, as he was afraid there was something the matter.

Shortly afterwards he told the fireman to jump off, having reversed the engine, as he saw a train of empty carriages on the line. The railway is a single branch line, and these carriages were ahead of them on the same line. When he first saw them, they were not more than forty yards from them.

The fireman did not jump off, but witness did. Although he had reversed the engine, there was still a good deal of way on the train behind.

He saw his engine run into the train of empty carriages as soon as he had jumped off. He got up to the engine as quickly as he could, when he saw the fireman on the tender-box bleeding. The guard of another train got him down, placed him on a carriage door, and he was taken to the hospital.

The footboard of the tender was smashed from the concussion. The empty carriages were on the sidings where the trains are made up. He could not tell what the first danger signal was for. The first he knew of an obstruction on the line was when he saw the empty carriages. There is a curve of the line there. The man who gave the danger signal was on the Brighton line, near the carriages. He could not see for more than thirty yards from the place where he stood.

[...]

Joseph Eastwood said he was foreman of the train makers at New Cross. He first saw the coal train come under the arch. It was the train that Boardman was driving. Witness was on the engine attached to the train of empty carriages. The engine has come from the shed at the top of the wharf, but the carriages had come from the siding. As they were going out of the siding the engine slipped, and they were obliged to go back some distance on the main line to get a better start, and had but just stopped when the coal train came up.

He could not see the coal train until it had got under the bridge. They put on the distance signal before they went down to the place where they were shunting. The man at the bridge could see it, to show that the line was obstructed. There was a corresponding signal to work further down the line.

He could not tell the reason why the distance signal was taken off, because the line was not clear. It was turned off some distance up the line.

As soon as he saw the wharf train he told the driver, and he jumped off the engine. The cause of the accident appeared to arise from some person having turned off the danger signal. The signal being copied by the man on the South-Eastern line would mislead the coal train.

John Stevens, bridge-lifter at the Surrey Canal, said he was stationed there. He saw the danger signal at New Cross, and he also put on his danger-signal. He saw nothing of the coal train when the danger-signal was on. It was on for twenty minutes, and it was then taken off. He could not tell the cause of the danger signal being on. After it was taken off, her saw the coal train go by, and saw no more of it until he heard a crash, and then he ran towards it. When he saw the coal train pass by, he did not know that there was a train of empty carriages on the same line.

He did not know whose duty it was to attend to the signal at New Cross. He saw the danger signal one hundred yards from New Cross.

Eastwood was recalled, and he said there had just before been a Dover train on the line, and when it went out, he told Moore, the guard of it,not to put the danger signal off. He could not tell if it had been turned off or not, as the signal was too far off.

Stephen Moore, guard on the South Eastern Railway, said he was with a train on the siding on the 27th of August, but he saw the train of empty carriages. The driver did not tell him not to take off the danger signal, and never spoke to him.

Eastwood reiterated that he was the man he spoke to, and told him not to take off the danger signal. He was taking trucks off, and having to pass through two pair of points, he held them for him. He saw no person touch the danger signal. He saw Moore go away soon after with the South Eastern train. That was before the accident occurred. If he had left the signal on, he should have turned it off when he had finished his work. He did not know who turned it off.

Captain Barlow said, as allusion had been made to the South Eastern Railway, he begged to take exception to the evidence, as these signals were on the Brighton line, and were not under the control of the South Eastern company.

William Barkwright, an engine driver, said he was with Moore when they were getting some trucks from the siding. He never heard Eastwood say anything to him about his train. Moore turned the danger signal off because they had done their work. Eastwood's train was shunting when he turned off the signal. Edgington took care of the signals. If he had to go away for any purpose, the signal took care of itself [Great surprise].

The Coroner: If Eastwood was shunting about with his engine, how came Moore to turn off the danger signal?

Witness: Because he left the signal as he found it.

The Coroner: But why, if another train was about?

Witness: Because he supposed that Eastwood would attend to that, Moore turned it off because he had done with it.

The Coroner: Then you knew that another train was about, and as Moore went and turned the signal off, do you suppose it was Eastwood's duty to go and turn it on again?

Witness: Yes, sir.

To a juror: There is no signalman there, nor has there ever been one.

Mr J Bayfield, house surgeon, said the deceased was brought into hospital with a compound fracture of the left leg, and also the thing on the same side. He went on well for some days, but in consequence of internal injuries he became weaker, and died on Saturday last.

The coroner then addressed the jury at some length, and said that if they considered there was criminality against Moore, he would adjourn the case for further evidence, but if they thought that it was only a case of want of judgement, they would return such a verdict as the nature of the case required.

The jury said, although they considered the death of the deceased was accidental, yet they were of opinion that blame attached to the company in not making better arrangements.

Mr Farmer said that arrangements had already been made, as experience had shown the necessity for a man being appointed whose sole duty it would be to look after the signals at this part of the line.

The inquiry was then terminated.

- From The Morning Chronicle, 13th September, 1853.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews