Elizabeth Fry Five Pound Note

Elizabeth Fry by Charles Robert Leslie

For more than a decade, the image of Elizabeth Fry has colonised pockets and purses right across Britain. It is ironic that her replacement by wartime leader Winston Churchill should coincide with the 200th anniversary of the act celebrated on the national currency, Fry reading to the unfortunate women imprisoned at Newgate Gaol, an event which was central to Fry’s penal reform project. Yet at the same time, both the anniversary and Fry’s retreat from public life, call for a reconsideration of exactly what is being remembered and what should be commemorated.

Elizabeth Fry by Charles Robert Leslie

For more than a decade, the image of Elizabeth Fry has colonised pockets and purses right across Britain. It is ironic that her replacement by wartime leader Winston Churchill should coincide with the 200th anniversary of the act celebrated on the national currency, Fry reading to the unfortunate women imprisoned at Newgate Gaol, an event which was central to Fry’s penal reform project. Yet at the same time, both the anniversary and Fry’s retreat from public life, call for a reconsideration of exactly what is being remembered and what should be commemorated.

Who was Elizabeth Fry?

Born Elizabeth Gurney on 21 May 1780 at Norwich, she was one of twelve children born into the wealthy merchant and banking Gurney family, and spent most of her formative years at the seventeenth-century mansion, Earlham Hall, in Norfolk. Although raised as a Quaker in ‘name only’, in 1798 a young Elizabeth decided to fully embrace the Quaker faith and traditions. Just two years later, she married tea merchant Joseph Fry, and the couple moved to London. In the intervals between child-bearing, Elizabeth became deeply committed to various charitable causes in the neighbourhoods in which she lived, for example: providing assistance and advice to poor women, co-founding a school for poor girls, and organising a smallpox vaccination programme for local children. In 1811, Elizabeth became a Quaker Minister.

Fry’s Newgate Narrative

Elizabeth first visited Newgate Gaol in January 1813 on the persuasion of her friend, Quaker missionary Stephen Grellet, to distribute clothing to the poor women confined there. As family commitments prevented any regular visiting at this time, Fry only seriously began to consider the plight of the Newgate women on her return to the Gaol in December 1816.

With relatively few historical sources on Fry’s early visits to Newgate, we have become largely dependent on the account provided by her brother-in-law, penal reformer Thomas Fowell Buxton, which was published in 1818 and subsequently used by other campaigners and later hagiographers. Buxton describes the terrible scenes of poverty and debauchery that Elizabeth encountered; women, scantily dressed, begging at the gratings, playing at cards, swearing, drunk and violent. Overcome with sadness, Elizabeth pulled out her Bible and began to read to them. It captured their attention – many of the women asked who Christ was.

Encouraged, over subsequent visits Elizabeth gradually put in place a new regime designed to reform the female prisoners. She organised a school for their children, appointed a female matron to guard them, procured useful work to occupy their time, formed a Ladies Association the members of which would visit, dispense advice, and give religious instruction, and laid down new rules policing prisoners’ behaviour. After winning the support of the inmates, in April 1817 Fry invited the Lord Mayor, Sheriffs and City Aldermen to the female side of Newgate secure their approval for the project. The men were ushered into a room where they witnessed Fry reading the Bible to the prisoners:

Their attention during the time of reading, their orderly and sober deportment, their decent dress, the absence of anything like tumult, noise, or contention, the obedience and respect shown by them, and the cheerfulness visible in their countenances and manners, conspired to excite the astonishment of the visitors.

Moved by the solemnity of the occasion, and the apparent transformation of the female prisoners, the authorities wholeheartedly gave their approval.

A Grand Historical Picture

![Jerry Barrett, ‘Mrs Fry Reading to the Prisoners in Newgate, in the year 1816’ (1860 [1863]) British museum](https://www.open.edu/openlearn/pluginfile.php/3275509/tool_ocwmanage/articletext/0/IMAGE_PIWN8Y.jpg) Jerry Barrett 'Mrs Fry Reading to the Prisoners in Newgate in the year 1816' (1860 [1863]) British museum.

Jerry Barrett 'Mrs Fry Reading to the Prisoners in Newgate in the year 1816' (1860 [1863]) British museum.

It was Jerry Barrett’s painting of this event that was used to celebrate Fry’s achievements in penal reform on the British Five Pound note. Or rather, a portion of Barrett’s painting. It is a rather cosy domestic scene. Fry is positioned in the centre, reading to a small group of attentive and penitent prisoners taking up the right-hand side of the image, while a group of well-dressed, noble personages, fill the left-hand side, and we know that these include reformers Joseph Gurney and Thomas Fowell Buxton, members of the Ladies Visiting Association, the Ordinary of Newgate, and likely another prison or city official. It provides an uncomplicated and uncontroversial statement of Fry’s success at Newgate, an example of the sympathy Fry had for the prisoners and her desire to improve their lives.

But there is so much more to Barratt’s painting. What is not reproduced on the five pound note are the prisoners who are not only inattentive but openly flouting Fry’s new rules – the two women gossiping over a bottle of porter, another secreting a deck of playing cards behind her friend’s back, and two boys squabbling over a set of dice with a discarded broadside at their feet. Their inclusion incorporates other important chapters in the Fry narrative, instances of transgression, as the prisoners struggle to reform. Buxton and many subsequent authors highlight the regret of those who show disobedience as well as Fry’s capacity for forgiveness. Barratt’s interpretation is somewhat more open-ended.

Because, ultimately, what Barratt sought to achieve with this painting was a ‘Grand Historical Picture’; an allegory, which would capture the most important elements of the Fry story. It is not, and was most likely never meant to be, a faithful representation of what actually happened at Newgate. After all, Barratt, born in 1824, had not been present at this or probably any of Fry’s readings at Newgate Gaol. And in 1860, when Barratt completed it, most if not all of those who appeared in the picture had passed away.

Newgate Uncovered

Using alternative historical sources, it is possible to draw a more accurate picture of Newgate Gaol, the women confined there, and Fry’s famous readings.

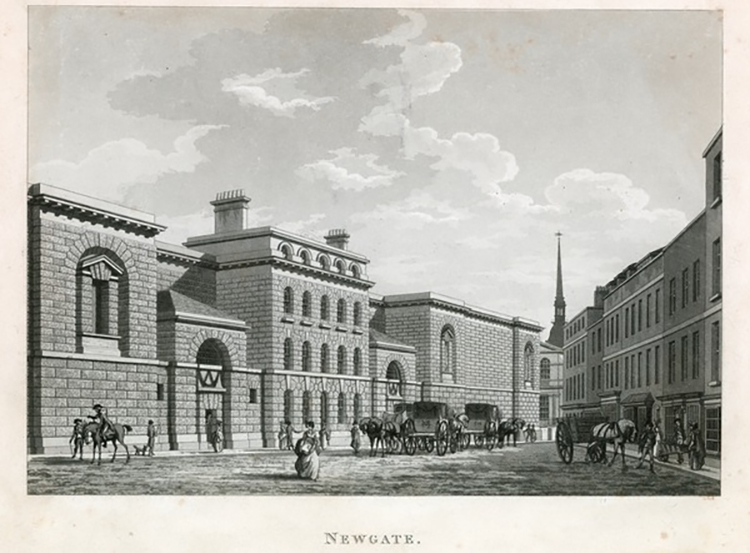

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

First, the Gaol. Like other contemporary penal reformers, Fry was keen to emphasise the terrible conditions at Newgate, especially the dirt, the drink and the depravity. In contrast, prison officials, anxious to maintain the status quo, often emphasised the orderly behaviour of inmates. The truth lies somewhere between the two accounts, recoverable in part from the prison records. The prison had been rebuilt in 1780, but faced problems of overcrowding from the outset. No formal system existed for handing out necessities such as soap, clothes and shoes to prisoners, but such items were distributed, and even passed through the gratings by prisoners to more needy family members on the outside. Prisoners could purchase food to supplement their rations, but many did not have any money. The system of self government allowed to exist alongside official discipline could both protect rights and entrench abuse. Crucial reforms had been enacted by 1816 – the abolition of fees, the separation of male and female prisoners, and the establishment of a supervisory visiting committee – but on the whole were probably too limited.

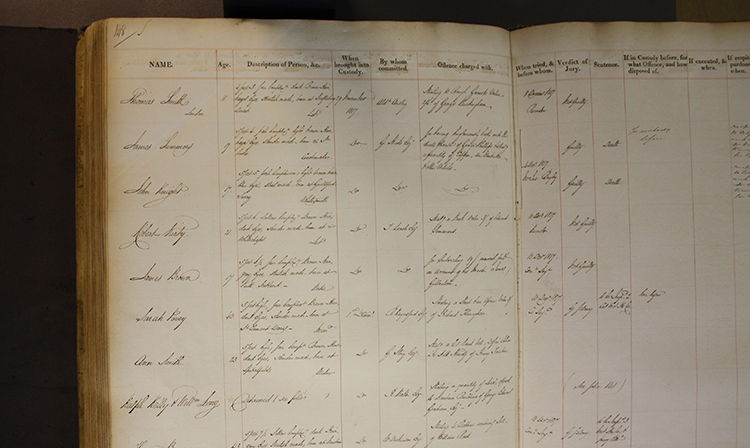

Second, the women. Fry later described them as ‘wild beasts’. While official records draw attention to instances of orderly and disorderly conduct, a number of the habits which offended Fry and her ladies were common practices, survival strategies or leisure activities, in working-class culture. The stories of individual prisoners told by Fry and other reformers to promote the Newgate project don’t provide much insight into the typical female prisoner or their experience at Newgate. Prison journals and registers do give us a brief snapshot of the women’s crimes, personal details and punishments. Most were unmarried, under the age of 30, convicted of theft and sentenced to transportation. While it is true that in the first few months of Fry’s visits, around two-thirds of the women confined for substantial periods while waiting for dispatch to the penal colonies (many for six months or more), this was not typical. Newgate Gaol was a transitory place. The prison was filled with the unconvicted in the lead up to the Old Bailey Sessions, then emptied soon after as most of those sentenced to imprisonment were delivered to the House of Correction, those sentenced to transportation were allocated places on ships or sent to Millbank, and those sentenced to death (a decreasing number) were promptly dealt with. Thus, between 1817 and 1835, between 200 and 400 convicted female prisoners ‘did time’ in Newgate each year, but many departed within a week.

Image of Newgate Gaol Register

Image of Newgate Gaol Register

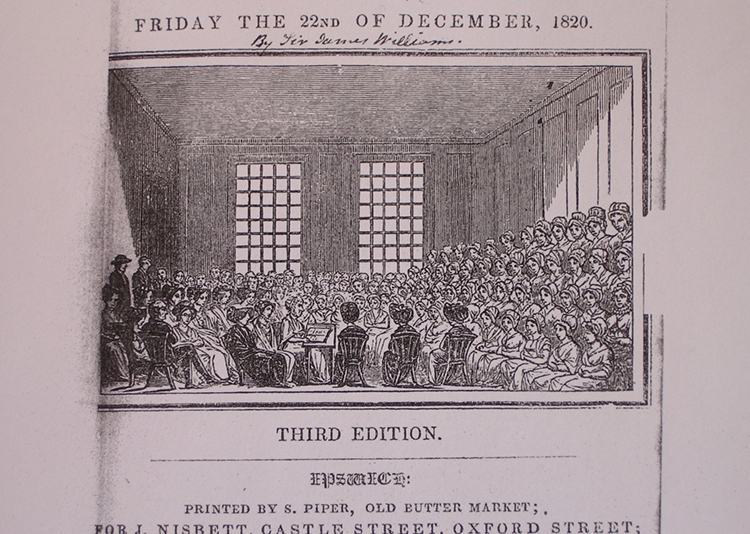

Third, the readings. Among the historical sources, Barratt’s painting stands out as just about the only depiction of a cosy domestic environment in which Fry’s readings took place. Eyewitness accounts, not to mention Fry’s own description of her regime, suggest that the daily Bible readings were much more regimented, even stage-managed. The special room set aside for the purpose, sometimes called a ‘lecture room’, had tiered seats rising above a central seat placed at the front of the room for the reader. The prisoners were called by a series of bells, the first to prepare and the second to file in. The prisoner’s voice was deliberately muted: no one was allowed to speak, certainly not with the reader, and time was allocated for silent reflection. Visitors were permitted to attend on Fridays, and so popular was the event that a ticketing system was established. These social elites were deeply affected, some even moved to tears, just like the female prisoners, they claimed. The new prison inspectors were less than impressed: in 1835, they found prisoners excluded from the readings to make space for visitors, and those fortunate enough to attend distracted by the sight of noble personages.

'An Hour in Her Majesty%u2019s Gaol at Newgate' (1820):

'An Hour in Her Majesty%u2019s Gaol at Newgate' (1820):

Aftermath

Just as Fry’s readings to prisoners at Newgate were complicated events with uncertain consequences, so too were her related schemes, such as the reformatories for released prisoners and naughty girls, and her efforts to organise convict ships. Evidence of institutional change and individual reform must be balanced with evidence of failure and rejection. That is not to dismiss her legacy, which is both multifaceted and lasting, not to mention worth remembering. While elements of Fry’s work could be highly detrimental to those she intended to help, she did promote a new and enduring ideal of compassionate and sympathetic social relations across the Western world in the modern age.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews