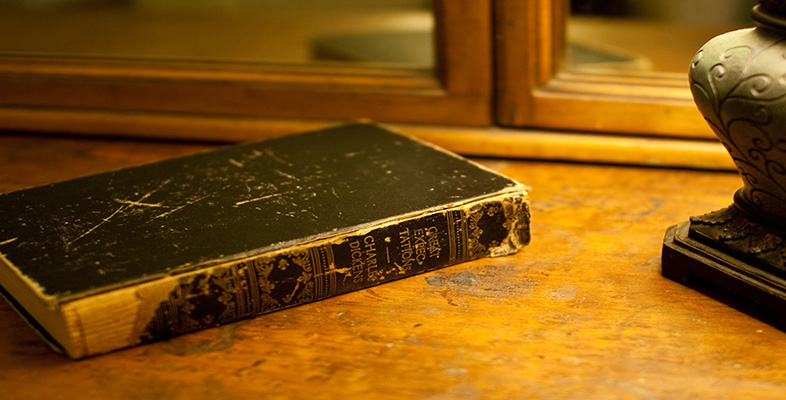

1 Openings and ogres

1.1 The novel's opening

One important way of approaching the novel as a genre is to think about what expectations this kind of text would have aroused in its first readers. This is a way of reminding us of the gap between then and now, of the fact that readers of the original novel had certain assumptions, which would have been different from our own. It is a way of remembering the changing cultural-historical context, which will help us to make sense of a text, but also of reading with more awareness of what the process of reading involves. In order to help us to think about how our reading may be influenced by our conventions and assumptions, I would like briefly to consider a modern novel, which raises these issues quite sharply.

Activity 1

Here is the opening paragraph of a novel published nearly a century-after Great Expectations. How does it capture the reader's interest? What literary tradition or sub-genre is being referred to and why? What features, if any, does it have in common with the opening pages of Great Expectations?

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two haemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them. They're quite touchy about anything like that, especially my father. They're nice and all – I'm not saying that – but they're also touchy as hell. Besides, I'm not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything. I'll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around Christmas before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy. I mean that's all I told D.B. about, and he's my brother and all. He's in Hollywood. That isn't too far from this crumby place, and he comes over and visits me practically every week-end. He's going to drive me home when I go home next month maybe. He just got a Jaguar. One of those little English jobs that can do around two hundred miles an hour. It cost him damn near four thousand bucks. He's got a lot of dough now. He didn't use to. He used to be just a regular writer, when he was home …

Discussion

This is the opening paragraph of The Catcher in the Rye (1951) by J.D. Salinger, and, like Great Expectations, it aims to capture our interest by immediately plunging us into the experience of an individual character, who tells us his story. As in Dickens's novel, that character is a young boy somewhat at odds with the world around him, in a way both funny and pathetic. The narrator in the modern novel explicitly recalls Dickens's David Copperfield (1849–50), but mentions the hero of that book only to deny that he is going to write the ‘kind of crap’ Dickens wrote and going on to assert that he will not tell us his ‘whole goddam autobiography or anything’ either.

The tendency towards exaggeration in the Salinger passage reflects a characteristic of young people's speech, but the form and content of the opening also establish a number of points about the text. First, the modern author is consciously participating in a tradition of first person, autobiographical narrative fiction, which Dickens helped to establish. This form of writing conventionally begins with an account of the narrator-hero's origins, childhood and parentage. Secondly, we are being reminded of that tradition or sub-genre in order to enjoy a consciously rude reaction against it. Thirdly, for all the naïvety of the narrator of the modern text, the author behind him is hardly naïve. Are we not, for instance, meant to feel more critical towards the boy narrator's family than he does? You might also have noticed that the specific allusion to David Copperfield clarifies the child narrator's gender, which is reinforced by the ‘pretend-tough’ tone. In Great Expectations, Philip Pirrip's name signals the gender of its autobiographical narrator, who is not going to tell us much about his parents either, not because they are touchy, but because they are dead. He, too, ignores or omits a lot of the ‘David Copperfield kind of crap’, although not in a self-aware, modern way.

Comparison of the two openings enables us to notice rather forcibly Dickens's manner of appealing to his readers. His narrative is first person, but, unlike the Salinger text, it involves an adult narrator looking back over a considerable time and so able to exercise adult judgements about himself. For example, he says that it was a ‘childish conclusion’ of his young self to imagine his dead mother ‘freckled and sickly’ on the basis of the gravestone inscription ‘Also Georgiana Wife of the Above’ (Dickens, Great Expectations, 1994 edn, p.3). We may also notice that what the narrator calls childish, in perhaps the negative sense, may be thought of more positively, in terms of a child's unconsciously acute perception of his mother's likely condition, at that time and with all those young and presumably sickly children. (I am not suggesting that any reader would think about all this on a first reading, by the way.)

This distancing effect, pulling us back to the adult narrator's perspective, and then further, to our own reading of that narrator's views, is reinforced by Dickens's way of handling time. Salinger uses the present tense, and his child narrator looks back just less than a year. Dickens uses the past tense, and has his narrator moving swiftly from a succinctly generalised past to ‘a memorable raw afternoon towards evening’, when the boy Pip realised ‘the identity of things’, and recalled himself as what the narrator goes on to call a ‘small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry’ (pp.3–4). The shift to the continuous tense brings the experience of feeling like a fragmented individual at the mercy of the elements right up into the present of its telling.