1.2 Perspective

Perhaps the most striking thing about the opening of Great Expectations is the way it combines the rhetorical immediacy of the speaking voice, and the closeness to the reader that invites, with this flexibility between different perspectives in time. Dickens thereby combines the ancient storyteller's art with more recent developments in narrative technique.

By ‘recent’, I have in mind the development of first person written narrative in the nineteenth century. There was a growing interest in the idea of a narrative retrospectively discovering a pattern of development in the young mind from within. (This was usually male, although Jane Eyre (1847) is the notable exception.) This type of autobiographical fiction is sometimes given the label Bildungsroman or apprenticeship novel (from Johann von Goethe's influential narrative of this type, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship (1795–6)). However, a ‘confessional’ element, derived from religious (especially puritan) tradition, was equally important in the formation of the sub-genre.

In this kind of narrative, the moral focus on the individual, which, as we have seen, was central to the formation of realist fiction, became mapped onto stories of the thoughts and adventures of childhood. Most of the earlier authors working within the autobiographical sub-genre chose to tell their story from the perspective of the adult, rather than as if it were spoken by the child or adolescent. The latter could not be expected to express feelings or analyse situations except within a limited range and remain credible, and so could only offer the most indirect or attenuated sense of moral or spiritual values. The characteristic modern version of this type of narration was established by James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). The Catcher in the Rye shows the continuity of the modern way of representing the inner workings of the mind, in terms of an inner monologue or ‘stream of consciousness’, which aims at authenticity rather than morality.

As novelists themselves have long recognised, the choice of what ‘point of view’ to adopt is one of the most important decisions they have to make. Theorists have gone on to isolate many different aspects of this decision, perhaps the most important being the distinction between ‘who speaks’ and ‘who sees’. In the opening of Great Expectations, the speaker is the adult Pip, but the child Pip is the one who sees. This gap is vital for the exploration of memory as well as morality in the novel, and as it proceeds the adult narrator's voice and comments play an increasingly important part in the way the narrative is mediated.

The dual role or perspective is established from the first words, if only by implication:

My father's family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.

This is the voice, not of the boy himself, but of the man, who can refer with light-hearted irony to the inadequacies of the ‘infant tongue’. In an act of self-identification explained by the next paragraph, the child gives himself a name associating him with his dead father, even as it registers his isolation from his unknown family. (Father-figures are especially important in what follows, as we shall see.) The second paragraph of the novel reinforces the suggestion of the creative power of the boy ‘fancies’ or imagination, at the same time as it offers a critical perspective upon that power: reading the grave inscriptions leads to unreasonable or childish images, which nonetheless sway us with their sympathetic or comic force.

The defining moment of Pip's life which follows is rendered with a touching melancholy, ‘a memorable raw afternoon towards evening’ (p.3), when childish fantasy is dissolved by the reality of the overgrown churchyard, his dead family and its gloomy environment. His sense of isolation and fear is suddenly dramatised by the appearance of the gruff stranger who threatens to murder and even eat him. The eruption of direct speech (‘Hold your noise!’), as a man ‘started up from among the graves’, takes us directly into the frightening present again: ‘A fearful man, all in coarse grey, with a great iron on his leg’ (p.4). Did you notice how this paragraph presents the man as the boy first sees him, with the minimum of narrative interference, by omitting the verbs from the first two sentences?

Activity 2

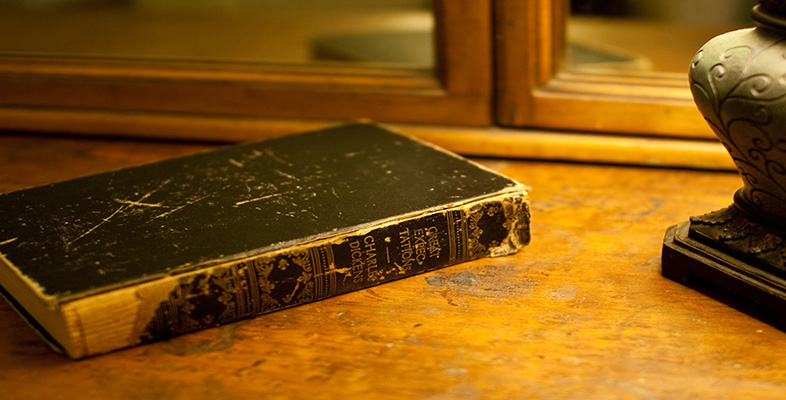

The first shocking appearance of the convict (well caught in David Lean's memorable film version of the novel, see Figure 1) brings into play another set of associations, which are critically important for our sense of the kind of novel we are dealing with here. How are we to respond to the convict's first appearance? By what means does the narrator mediate the ‘reality’ of this character to us?

Discussion

The convict's opening words (‘Hold your noise! … Keep still, you little devil, or I'll cut your throat!’, p.4) have just the exaggerated unreality we would expect of a stage or fairy-tale monster. Yet I think we accept his ‘reality’ because of the way Dickens presents the character: by making him not only something threatening as seen by the shivering child, but also something comic, as he becomes when mediated to us by the narrating adult. The humorous, ironic effect emerges, for instance, when the convict himself momentarily takes fright as Pip indicates that his mother is ‘There, sir!’ in the graveyard (p.5). The effect is confirmed when the convict tells Pip that if he does not do as he is told, there is a young man who will ‘get’ him even when he thinks he is safe in bed (‘in comparison with which young man I am a Angel’, p.6). Pip is terrified, but we are not – nor, clearly, are we meant to be. The distance between who sees and who speaks in this situation is explicitly indicated by the narrator's words when he describes the impression made upon young Pip as the convict leaves: ‘he looked in my young eyes as if he were eluding the hands of the dead people, stretching up cautiously out of their graves, to get a twist upon his ankle and pull him in’ (p.7).

With superbly grotesque precision – ‘cautiously’ seems particularly apt – Dickens suggests the fearful closeness of living and dead to the young Pip. At the same time, the boy's fancy anticipates something of importance for the novel as a whole, which may well work upon us unconsciously in a first reading. This is the power of the dead, the forgotten or unseen, unexpectedly to influence our lives. The manner of narration invites sympathy and understanding for the child Pip, but by reminding us of the adult narrator it offers a more detached perspective as well, making possible the ironic humour that plays about the entire narrative. The initial conception of the convict suggests gothic melodrama, but it is melodrama incorporated within a subtle artistic medium to produce complex effects within the reader.

Why does the term ‘gothic’ seem appropriate? Well, surely, the figure that ‘started up’ into Pip's view with such suddenness ‘from among the graves’, with his frightful glaring and growling, reminds us of that other creature from the dead who, as you may recall, caused a frightened young boy to cry out as he struggled: ‘Let me go … monster! ugly wretch! you wish to eat me, and tear me to pieces – You are an ogre’? Of course, Frankenstein's creature goes on to kill his victim (Shelley, Frankenstein, 1994 edn, p.117), whereas, for all his ogreish aspect, the convict in Great Expectations does not and, as we soon realise, would not. Shelley's creature tells his own story, distanced by being told to another narrator, whereas Dickens's ‘monster’ is seen from his potential victim's point of view. This makes his presentation in terms of what we might read as ‘gothic’ excess in fact rather plausible, since it can also be understood as the product of a young imagination replete with the monsters and ogres of folk and fairy-tale tradition. Moreover, this is a young imagination already sensitised by long infant meditation upon the family gravestones, amid the dreary winter marshes.