3.2 Moral development

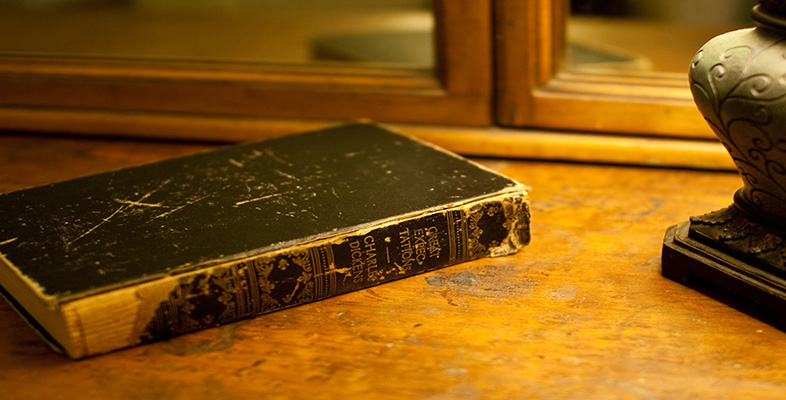

I want to stress this aspect of Dickens's kind of fiction, because he is so often thought of as the novelist of the stereotypically obvious, with his tyrannical men, dried up women and pathetic children. Although there may be nothing wrong with being obvious, the point about Great Expectations is that it is most persuasive when it is not obvious. Various critics have tried to point out what is obvious about the novel (see, for example, Q.D. Leavis's ‘How We Must Read Great Expectations’) but the struggle to do so makes it seem less and less obvious. From the title, with its ambivalent overtones, to the two endings, neither of which is unambiguous, this is surely a novel that resists tying down to any simple message or summary?

It could be argued that one of the things it is about is precisely the inadequacy of the obvious. This is a function of its multi-genre status. If, for example, the novel seems obviously a classic story of self-education, of the rise of a young man from his rural roots towards metropolitan sophistication, then it also appears to undermine this very familiar Victorian tale. As Kate Flint says in the introduction (p.xvii), Pip's Bildungsroman is the ‘antithesis’ of those well-known and widely read contemporary chronicles of humble perseverance, such as Samuel Smiles's Self-Help (1859), which it calls to mind. Flint also relates Great Expectations to the contemporary vogue for sensation novels exemplified by Dickens's friend Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White (1860), with its ‘combination of crime, violence, a self-sequestrated woman, and the revelation of her ward's parentage’ (p.viii), although Dickens's book is also more than a novel of mystery and suspense. Flint proposes that Great Expectations is best seen in terms of the broad form of fictional autobiography. This is in line with her overall emphasis upon the novel's dramatization of ‘the issue of identity’, by means of which it participates in mid-Victorian attempts to show that work, loyalty and compassion are their own reward, while leaving ‘uncertain how Pip may prosper in the busy society of modern, urban Britain’ (p.xxi).

Activity 5

This impression of variety and uncertainty about the novel's status brings us back to the approach I am putting forward here: that we think about reading it as a text which draws on a mixture of artistic conventions, offering a multiplicity of meanings, depending upon which genre-frame or set of strategies we emphasise as readers. This is not to deny that to read the book only as an education novel is revealing, and makes sense of the story as a tale of personal moral development. To prove this point, first try and summarise the novel as a tale of individual moral development, and then consider what such a summary leaves out.

Discussion

This is the story of an orphan, Pip, who is brought up by his sister and her husband, the village blacksmith. Pip encounters and helps an escaped convict, and is later sent to call upon an eccentric heiress, whose ward, Estella, makes him despise his lowly origins, and with whom he falls in love. When Pip is of age, the heiress pays for him to be apprenticed as a blacksmith, but four years later he is told he has expectations of great wealth from a secret benefactor, whom he assumes to be the heiress. He departs to enjoy his good fortune in London, where he neglects his family and old friends and lives a life of dissipation and idleness. Pip's benefactor turns out to be the convict he met as a child who is recaptured and sentenced to death, with the loss of the wealth he made when he was deported to Australia. Meanwhile, Estella marries a boorish young man. Pip is left penniless and ill, but is nursed by his foster-father the blacksmith, who pays his debts, and from whom he learns humility and compassion. He finds work through a friend whose career he aided in secret during his time in London. Finally, he discovers that Estella has been mistreated by her husband and is humbled and a widow. However, the story does not make clear whether or not they eventually marry.

This is accurate as far as it goes, although even such a bald summary suggests the romance contours of the book's structure, its fanciful pattern of ironic revelation and its odd mixture of realistic and gothic or melodramatic associations. It is the latter two associations that take it beyond the plain articulation of a Bildungsroman. What such a summary most obviously leaves out is Pip's inner life.