4.3 Death

I am not trying to suggest that we ignore Said's criticism. On the contrary, he provides a salutary reminder of that ‘other’ history of Dickens's times, that is, the colonial history, which any attempt to relate his work to its times needs now to negotiate. Rather, I am trying to suggest that the criticism should prompt us to look again at the key characters, events and relationships in the novel, with an awareness of the uniquely mixed genre that it puts forward.

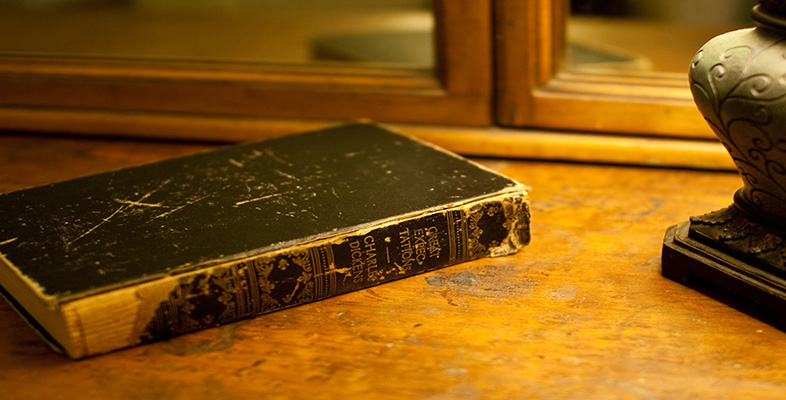

In the limited space I have left here, I would like to consider once again how Dickens deals with the relation between Pip and Magwitch. This relation, it seems to me, offers the truly subversive potential of the novel. Considering this potential may enlarge our understanding of imperial Britain of the 1850s and 1860s, a time of high achievement whose legacy is with us yet. Of course, there is a convincing realism in Dickens's characterization of both boy and convict, even when they meet on that stereotypically Victorian setting, a deathbed. Here Dickens troublingly allows Pip to express his profound pity for the outcast by revising the well-known biblical prayer from Luke 18:13, ‘God be merciful to me a sinner’, in a way that suggests a pharisaical perversion: ‘O Lord, be merciful to him, a sinner!’ (p.455). The remarkable, detailed account of Magwitch's trial and sentencing, which precedes the deathbed scene, is witnessed by Pip as a young man, but it is depicted by the older narrator as a memorable tableau, which takes us into another, symbolic dimension.

Activity 9

Why do you think that Dickens wrote in this way here?

At that time it was the custom (as I learnt from my terrible experience of that Sessions) to devote a concluding day to the passing of Sentences, and to make a finishing effect with the Sentence of Death. But for the indelible picture that my remembrance now holds before me, I could scarcely believe, even as I write these words, that I saw two-and-thirty men and women put before the Judge to receive that sentence together. Foremost among the two-and-thirty, was he; seated, that he might get breath enough to keep life in him.

The whole scene starts out again in the vivid colours of the moment …

The sun was striking in at the great windows of the court, through the glittering drops of rain upon the glass, and it made a broad shaft of light between the two-and-thirty and the Judge, linking both together, and perhaps reminding some among the audience, how both were passing on, with absolute equality, to the greater Judgement that knoweth all things and cannot err. Rising for a moment, a distinct speck of face in this way of light, the prisoner said, ‘My Lord, I have received my sentence of Death from the Almighty, but I bow to yours,’ and sat down again.

Discussion

Dickens's imagination in this highly charged, significant moment is extraordinarily visual. Pip recalls the scene which, as he says, ‘starts out again’ in ‘vivid colours’, the shift into the present tense reinforcing the shift into a static, apparently timeless mode, slowing down the entire narrative. Surely Dickens used this technique to create in readers a sense of a much larger perspective, a perspective that does infinitely more than just enhance the drama of the moment? It calls on the contemporary awareness of popular depictions of such scenes to question the law, and the society whose attitudes it embodies. If you look at the complete passage, you will notice that Dickens gives us the judge's speech condemning Magwitch as an offender from infancy, ‘a scourge to society’ (p.452), but this view is then radically challenged by the ‘broad shaft of light’ that links the two together in equality before death.

It is clear that we are being taken into a dimension beyond realism. I have said that the scene takes us into a symbolic dimension to stress its static, visual quality, although it could almost be called allegoric in its clarity and moral significance. It is, in fact, probably derived from a famous engraving by William Hogarth called Paul Before Felix (1748), which Dickens would have known. In this Saint Paul stands before a Roman judge on a trumped-up charge of riotous assembly, a divine light shining aptly on him from behind his accusers as he appeals to a higher authority to justify him. We do not need to know this to respond to the appeal inherent in Dickens's elaborate picture. It may be helpful though to realise that behind it lies a popular, native tradition of graphic satire, typically anti-establishment and anti-authoritarian. It is another aspect of the novel's close incorporation of non-realist traditions of representation.