4.4 Summary

The way in which this important scene at the defining moment of the Pip and Magwitch story has been imagined implies the deep connection between the highest and the lowest. Once we accept this connection, we can read the narrative afresh as the source of currents of implication which at least question its own tendency towards accepting the status quo. We can go further, turning Said's view upside-down, and argue that it is one of this novel's greatest strengths to assert, with whatever qualification, in an imperial age the deep connection between the achievement of wealth, status and happiness in Britain and the misery, humiliation and deprivation of those condemned to be its underclass, and sent abroad to colonise a land nobody wanted to think about. Pip's resistance to Magwitch in the hallucinatory, dream-like recognition scene that opens the third volume of the book can be seen to express the resistance of all those in his society who would rather not know about the source of their position or their country's pre-eminence. The realist features of that sequence – it has a filmic quality – ensure that we as readers are drawn in as we, through Pip's eyes, meet ‘A.M. come back from Botany Bay’ (p.329), with his ‘blast you every one, from the judge in his wig, to the colonist a stirring up the dust’ (p.328) (Magwitch at least knows that even out there we find a class system), with his pocket-book, his ‘greasy little clasped black Testament’ (p.330), his clasp-knife and his appallingly ungenteel manner of eating – ‘in a ravenous way that was very disagreeable … Some of his teeth had failed him since I saw him eat on the marshes, and as he turned his food in his mouth, and turned his head sideways to bring his strongest fangs to bear upon it, he looked terribly like a hungry old dog’ (p.327).

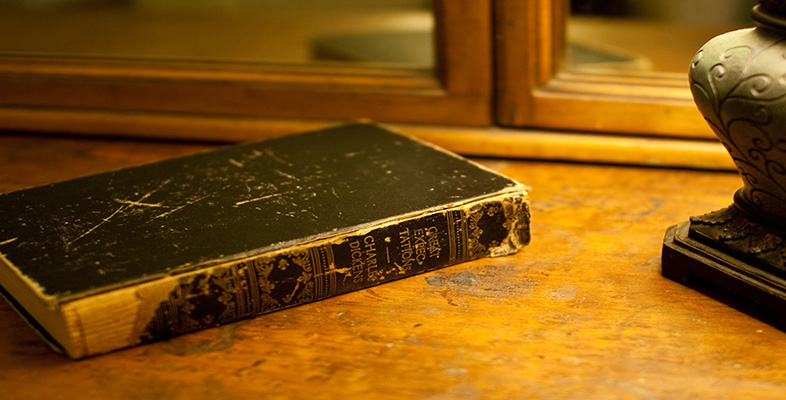

As with any great novel, there are always further possibilities. Reading Great Expectations with an active awareness of Dickens's kind of writing, we could pursue, for example, the fact that, according to Robert Hughes's book on the convict settlement of Australia, one of the most notorious escapees was an Irishman transported in 1819 for seven years for stealing six pairs of shoes, who resorted to cannibalism to survive (The Fatal Shore, 1987, pp.220–6). The way people eat in this novel, and in particular the way Magwitch feeds (a ‘Bolter’, unlike the young Pip who is only accused of this by Joe), carries some strange and unexpected overtones, which would bear investigating, but not now. Now is the moment to leave Great Expectations to you, and your further reading of it.