2.3 Acts 3 and 4: What does Faustus achieve?

Act 2 points repeatedly to the failure of Faustus's attempt to secure power and autonomy through his pact with Lucifer: in Act 2, Scene 1 Mephistopheles declines his request for a wife, and in Act 2, Scene 3 he refuses to tell him who made the world. Acts 3 and 4 cover the bulk of the twenty-four-year period that Faustus purchased with his soul. How do they make us feel about what he actually achieves through his embracing of black magic? Are we encouraged to feel it was worth it?

Activity

Please have another look at Act 4, Scenes 1 and 2 (pages 35–43). On the basis of these scenes, would you say that Faustus has realised his dreams of power and pleasure? What evidence would you offer in support of your view?

Discussion

These two scenes show us Faustus in the role of court magician, entertaining the emperor Charles V and then the Duke and Duchess of Vanholt with conjuring tricks. Many critics have felt that these scenes highlight the hollowness of Faustus's achievements; far from realising his grand dreams of immense power, all he manages to become is the entertainer of the established ruling elite. Marlowe certainly makes a point in Act 4, Scene 1 of stressing the limitations of his protagonist's conjuring powers. Because Faustus is still unable to raise people from the dead, he can do no more than summon spirits who resemble Alexander and his paramour. In Act 4, Scene 2 the point seems to be not that Faustus lacks the power to fulfil the request made of him by his aristocratic employer, but that the Duchess of Vanholt can think of nothing more challenging to ask for than a dish of ripe grapes, to which Faustus replies, apparently with some regret, ‘Alas, madam, that's nothing’ (4.2.14). He seems at this point to share the view of many critics that he is squandering his abilities on trivial activities.

Yet is this all there is to say on this matter? As usual with this play, there is another side to the story, especially if we consider Act 3. Earlier we looked at Faustus's desire to ‘chase the Prince of Parma from our land’, and speculated how, in a climate of military conflict with Spain, it might have endeared him to the play's original audience. At the time of the play's first performances, the Catholic Church would have been viewed by many with comparable hostility. In 1570 the Pope had excommunicated Elizabeth I and released her Catholic subjects from their allegiance to the Protestant heretic queen; in 1580 he proclaimed that her assassination would not be a mortal sin. Read with this context in mind, Act 3, Scene 1, in which Faustus makes a fool of the Pope under cover of his magician's cloak of invisibility, looks like a bid for audience approval, by its portrayal of the Catholic Church as decadent and corrupt, and mired in absurd superstitions like the ceremony of excommunication. By casting Faustus in the role of Protestant hero, this scene seems designed to elicit a favourable response to his conjuring skill.

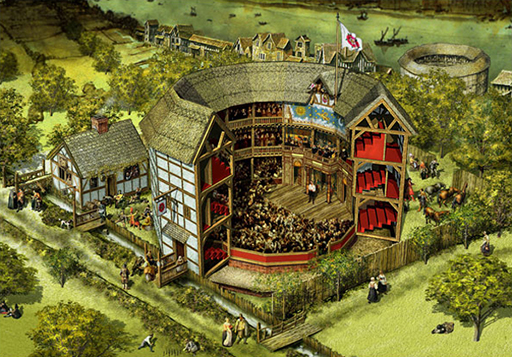

We need to remember as well the limitations of the theatre, in particular of Marlowe's open-air theatre, where plays were performed in broad daylight with little in the way of props, scenery or artificial lighting see Figure 4). In these conditions, it is not hard to grasp why so many of Faustus's adventures as a magician are reported rather than enacted: the Chorus to Act 3, for example, tells us that in order to learn ‘the secrets of astronomy’ (3.1.2), Faustus scaled Mount Olympus ‘in a chariot burning bright / Drawn by the strength of yoky dragons' necks’ (3.1.5–6). This sounds anything but a hollow experience, and when discussing Acts 3 and 4 we should give due weight to the descriptions Marlowe provides of activities he was unable to enact on stage, especially given that these descriptions probably had a powerful impact on the play's original audience, who were much more accustomed to listening to long and often complex speeches (sermons, for example) than we tend to be nowadays.

The mention of the play in performance leads us to an important characteristic of drama, which makes it different from other literary forms such as the novel and poetry: plays are written to be performed whereas novels and poems are written to be read. This means that a play is not so much a fixed and finished literary text as a blueprint for actors and directors who will have to make decisions about how it is going to be translated from the page to the stage. They will have to ask themselves questions, such as what is actually happening on stage at any given moment? How should a particular speech be spoken by the actor playing the part, and which actor is best suited to play the part? A director will also need to make decisions about set design, costumes, lighting, music and other sound effects. All of these aspects of performance will contribute to the meaning of the play, and they will differ from one production to another.

Activity

So how might consideration of Doctor Faustus as a text intended for performance affect our response to Faustus's career as a magician? A moment ago we discussed the way in which Act 4 in particular seems to emphasise the gap between Faustus's aspirations and his actual achievement. Does thinking about these scenes in terms of performance open up different possibilities?

Discussion

It strikes me that Act 4, Scene 1, for example, in which Faustus conjures up the image of Alexander the Great and his paramour, could easily, with the skilful use of music and lighting, be turned into a thrilling stage spectacle. It might then be possible to perform Act 4 in such a way as to create the impression not of the emptiness, but of the wonder of Faustus's magical powers.

The same might be said of the two appearances of Helen of Troy in Act 5, Scene 1. This scene is structured in such a way as to establish a clear contrast between Faustus's two encounters: with the Old Man, who urges piety and repentance, and with the legendary beauty Helen of Troy (Figure 5). Faustus chooses Helen, and many critics have echoed the Old Man's stern disapproval. Yet the critic Thomas Healy points out that in the theatre Helen is usually represented as so ‘strikingly beautiful’ that even if one agrees on a rational level that Faustus would be better off with the Old Man, on a visual level the Old Man loses out to Helen, who engages what Healy calls the audience's ‘emotional and aesthetic sympathy’ (Healy, 2004, p. 183). By the same token, a director might choose to portray Helen instead as a malign influence on the hero.