2.5 Morality play or tragedy?

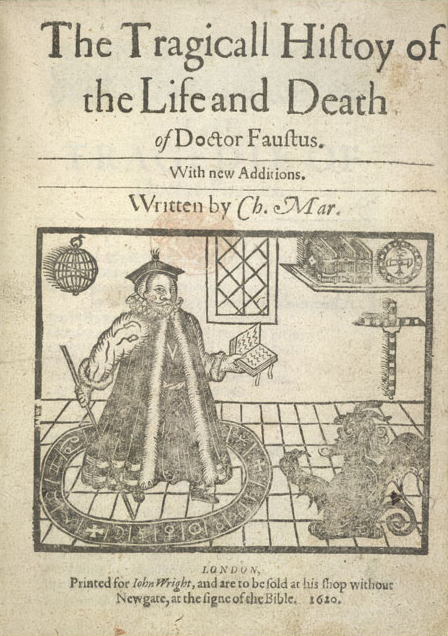

Pity and fear are the emotions that, according to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, are aroused by the experience of watching a tragedy. At the start of this chapter we asked whether Doctor Faustus is a late sixteenth-century morality play, designed to teach its audience about the spiritual dangers of excessive learning and ambition. When the play was published, first in 1604 and then in 1616, it was called a ‘tragical history’; if we take ‘history’ here to refer not to a particular dramatic genre but more generally to a narrative or story, then the publisher described the play as a tragic tale. So what is a tragedy? In fact, ‘tragedy’ is a notoriously difficult literary term to define, for it seems to take various forms in different historical periods. But for the sake of discussion, we can fall back on the broad strokes of Aristotle's description (in the Poetics) of the tragedies he had seen in Athens in the fourth century BCE: tragedies are plays that represent a central action or plot that is serious and significant. They involve a socially prominent main character who is neither evil nor morally perfect, who moves from a state of happiness to a state of misery because of some frailty or error of judgement: this is the tragic hero, the remarkable individual whose fall stimulates in the spectator intense feelings of pity and fear.

To what extent does Doctor Faustus conform to this description of a tragic play? Well, it follows the classic tragic trajectory in so far as it starts out with the protagonist at the pinnacle of his achievement and ends with his fall into misery, death and (in this case) damnation. From the beginning the play identifies its protagonist not as ‘everyman’, the morality play hero who ‘stands for’ all of us, but as the exceptional protagonist of tragic drama. Moreover, it is certainly possible to argue that Faustus brings about his own demise through his catastrophically ill-advised decision to embrace black magic. Perhaps most importantly, we have seen in the course of this course that Faustus is consistently presented to us as an intermediate character, neither wholly good nor wholly bad: both brilliant and arrogant, learned and foolish, consumed with intellectual curiosity and possessed of insatiable appetites for worldly pleasure, a conscience-stricken rebel against divine power. We have seen as well how skilfully Marlowe uses the soliloquy to create a powerful illusion of a complex inner life: from Faustus's first proud rejection of the university curriculum and his exuberant daydreams of unlimited power, to his anguished self-questioning and final terrified confrontation with the divine authority he defied, the play gives us access to the thoughts and feelings of a dramatic character whose fall, whether or not we feel it is deserved, seems to call for a fuller emotional response than the Epilogue's moralising can provide.