Last week, Ben John, a 21-year-old former criminology student at De Montfort University, was given a suspended two-year prison sentence and a five-year Serious Crime Prevention order for possessing neo-Nazi and terror-related documents. At his trial at Leicester Crown Court, it was revealed that John had amassed nearly 70,000 digital files relating to Adolf Hitler, Nazi ideology and white-supremacy and had also downloaded bomb-making manuals. Sentencing him under counter-terrorism legislation, the presiding judge, Timothy Spencer QC, cautioned John against accessing any such literature in future and ordered him to read canonical English literature instead, including works by Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, William Shakespeare, Thomas Hardy and Anthony Trollope. He warned John that he had narrowly escaped a custodial sentence and stated that he would be required to return to court every four months to be tested on what he had read.

John’s sentence has already been the subject of an Undue Leniency appeal by the counter-extremist charity Hope not Hate – and it may yet be changed if law officers review the case. Certainly, John’s sentence begs the question whether a young man of colour, and/or a Muslim, convicted of possessing literature promoting other forms of extremism, would have received a similar sentence. Another unusual detail of the judgement is also open to question: the assumption that those who hold violently racist views might be rehabilitated by reading works of English literature.

Most readers of literature in English would like to think that the process of reading improves or enriches them, and a common societal assumption is that reading is an intangible good: we encourage children to read on the grounds that it feeds the imagination, informs us about the world and teaches a kind of empathy through the different perspectives it affords. (More concrete evidence exists for the benefits of regularly reading literature – and being read to – for children’s cognitive development and educational attainment.) For those of us lucky enough to teach or study English literature, its rewards are often even more profoundly felt and yet difficult to quantify. Literature is an aesthetic experience and a solace, an entertainment and a time machine, an infinite store of ideas and experiences.

Does literature have the transformative power to change the perspective of someone with violent racist views, however? The logic of the judge’s pronouncement in this case is appreciable if puzzling: Ben John had been reading proscribed, highly offensive literature, so his sentence should involve reading different, ‘beneficial’ literature instead. Such a logic is reminiscent of the liberal humanist views promoted by nineteenth-century commentators such as Matthew Arnold who believed that English literature could be an important social palliative: ‘the best which has been thought and said’. These ideas were later developed by one of the pioneers of English literature as a critical discipline, F.R. Leavis, who argued for the power of ‘great’ literature as a safeguard against the alienation and shallow commercialism of the modern world.

These arguments became less tenable after the Second World War, when evidence emerged that many of the functionaries of Hitler’s Third Reich, including those directly involved in running concentration camps, were highly cultured and had combined an enjoyment of canonical literature and classical music with the banal daily horrors of industrial genocide. On these terms, is it conceivable that Ben John’s sentence might simply enrich him aesthetically but do nothing to change his violently racist views? Or might it actually teach him how to dissemble more effectively, following a long line of compelling fictional deceivers and self-deceivers so that he pretended to be reformed? Moreover, when we remember the UK’s Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, whose past pronouncements about Black and Muslim British citizens have been condemned, and who allegedly missed important COBRA meetings at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic because he was writing a book about Shakespeare, it is not at all clear that literary interests lead to progressive ideas about ethnicity and difference.

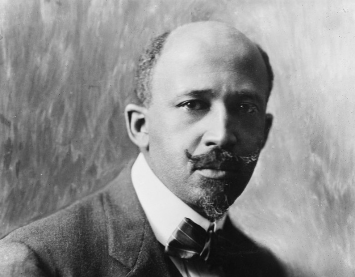

Why not start, instead, with the brilliant critique of racism that threads through the texts of African America?Even if English literature has the power to rehabilitate, is the judge’s syllabus helpful? At the very least, a reading list featuring four white men and one white woman, all but one from the nineteenth century, seems outdated. In a previous article I looked at Dickens' sometimes shocking views on race, and Jane Austen too is a problematic choice given (debatable and surprising) reports a few years ago that alt-right commentators favoured her monocultural novels as templates for ‘a white ethnostate’. Why not start, instead, with the brilliant critique of racism that threads through the texts of African America, from slave narratives, through the modernism of the Harlem Renaissance, to works like James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and Toni Morrison’s Beloved? Or if you wanted to expose the consequences of Nazi ideology, why not read Primo Levi’s searing If This Is a Man or Friedrich Reck’s Diary of a Man in Despair (Levi survived Auschwitz; Reck died in Dachau). Or perhaps to appeal to a 21-year-old, why not just direct him to the great coming of age novels of a multi-ethnic Britain, works such as Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth or more recently, and aptly in relation to extremist politics, Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire?

This alternative ‘rehabilitative’ reading list comes with no guarantees but it might do a better job of what Reni Eddo-Lodge describes as ‘dissecting political whiteness’ than the more invisible hierarchical racial values promoted by nineteenth-century fiction. Literature can certainly change people but the inclination to be changed is a pre-requisite, and selecting works that will have a relevance, and might have a chance of effecting change, is a small but crucial first step.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews