6 Calvinistic Methodism

As we have discovered, by the middle of the nineteenth century Calvinistic Methodism had become a popular form of Protestantism in Wales. At the moment, however, we are interested in its origins and early progress within the Church of England – indeed it was not until the nineteenth century that the Welsh Methodists formed their own confederation outside of the Anglican faith. Nevertheless, it was even then already a sizeable movement, claiming around 10,000 ‘hearers’ by 1750 and approximately 30,000 by the time of its secession from the Anglican Church in the 1810s (Field, 2012, p. 707).

Yet the development of the movement was far from smooth, and the early leaders of Methodism in Wales were frequently met with verbal and even physical abuse. The quote below, admittedly from a later source with a pro-Methodist bias, describes Howell Harris’s response to one such occasion:

An Association was one time to be held at Llandovery. Rowland, and Williams of Pantycelyn, and Howell Davies arrived there before Harris, and began the public service. But when they stood up to preach a fierce opposition arose: such a blowing of horns, beating of drums and kettles, ringing of bells, and throwing of missiles at those on the platform took place that Williams said ‘Brethren, it is impossible to go on here, in the midst of so much noise and danger; let us go to my residence at Pantycelyn, and hold the Association there.’ So they reluctantly started. But on the way Harris met them, and asked with great surprise ‘Where are you going?’ Williams replied ‘We are going to Pantycelyn; we cannot go on at Llandovery, for our life is in danger.’ ‘Life! Life!’ replied Harris, ‘is that all? Here is my life for the sake of Christ. Let us go back; they shall have this poor body of mine.’ So back they went, with Harris at their head. When they got to the platform, Harris stepped upon it with much boldness and firmness, solemnly crying out, ‘Let us pray,’ and the crowd were silent in a moment. He then prayed with such power and warmth that the people were overawed, and attended to the preaching with quietness and interest.

While Methodists were not under direct threat from the state as the dissenters of the 1600s had been, during the eighteenth century they were nonetheless still the object of considerable suspicion. This was a far cry from the ascendant Nonconformity that characterised much of Welsh society during the nineteenth century

Activity 3

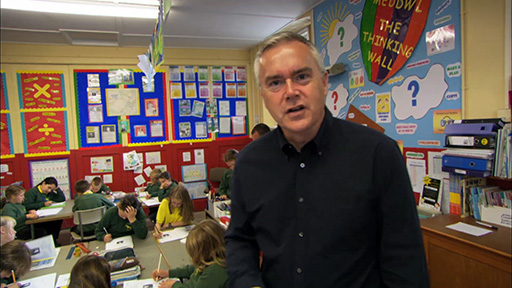

To get a sense of the rise and significance of Methodism in Wales, watch the clip below from the BBC television series The Story of Wales. Then answer the question.

Transcript: Video 1 The Story of Wales

[CHOIR SINGING]

[SINGING]

[SINGING IN WELSH]

How impartial and accurate do you think this clip is?

- impartial and accurate on all counts

- contains traces of bias, but it is a pretty accurate account of events

- biased, but the main points are accurate

- wildly biased and very inaccurate

Feedback

To my mind, this clip implicitly marginalises the Anglican majority in Wales by exaggerating the impact of Methodism and the other forms of Nonconformity that flourished in the period. Indeed, this is a good example of how attempts to tell the ‘story’ of a nation tend to distort our understanding of the past by excluding elements that do not fit the narrative that the storyteller has chosen. Nevertheless, the clip does make a direct link between rising literacy levels, thanks to Griffith Jones’ circulating schools, and the Methodist Revival. Although the programme simplifies that connection, it is right to emphasise the relationship between Welsh-language literacy and the evangelical fever which gripped Wales in the 1740s – a fever which boosted Nonconformity in general as well as contributing to the birth of Methodism.

Activity 4

As we learned earlier in the course, circulating schools were the brainchild of Griffith Jones, supported by the wealthy heiress Bridget Bevan. You can learn more about both of them in the Dictionary of Welsh biography [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . You can either search for a particular biography, or search for the individual you are researching in the text of the entries themselves.

While you are there, why not also look up Methodist leaders such as Howell Harris, Daniel Rowland, William Williams, Peter Williams and Thomas Charles. Try to read at least four entries (they are nice and short), although you should feel free to read more if you have the time. Then make some notes on what you have found out about Methodism in the box below.

What have you learned from the dictionary entries about Welsh Methodism?

Discussion

From looking at the biographies of eighteenth-century Methodist leaders in Wales, you have probably formed an impression of a religion based on powerful sermons, charismatic leaders and individuals experiencing religious conversions or awakenings. Indeed the 1730s and 1740s in Wales are often referred to as a time of ‘evangelical revival’, meaning a period of zealous and energetic preaching to spread the word of God. Services and sermons were conducted in Welsh and, as some of the entries mention, many Methodist preachers wrote and published both hymns and religious texts in Welsh as well. You may also have noticed that the movement’s early leaders tended to operate at the fringes of the Church of England, and were tolerated rather than celebrated by the Anglican hierarchy.