8 The Treachery of the Blue Books

One of the most significant events in the history of Calvinistic Methodism, and indeed of Welsh Nonconformity more broadly, occurred in 1847. This was the publication of the ‘Reports of the commissioners of inquiry into the state of education in Wales’, or the ‘Treachery of the Blue Books’, as they came to be known in Wales.

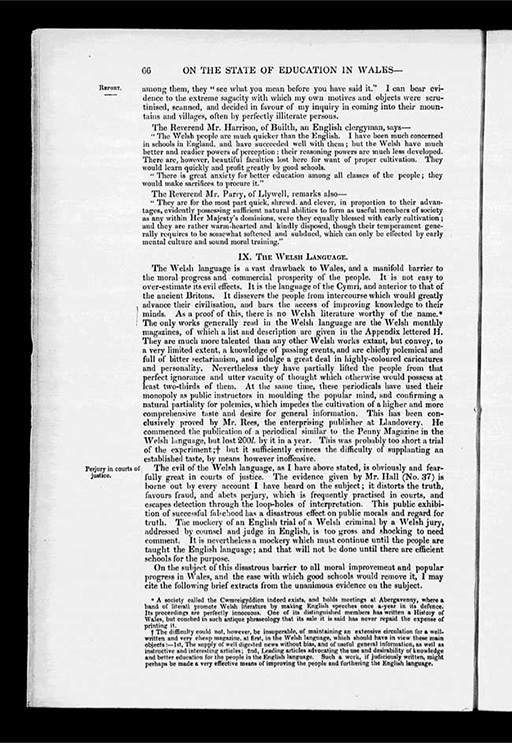

These reports were commissioned by parliament in Westminster, and written by three Anglican churchmen from England. They were commissioned specifically to provide a justification for the reform of education in Wales along anglicising lines (Roberts, 1998, pp. 168–179). It is therefore no surprise to learn that the three ‘commissioners’ cast the Welsh populace, and particularly the Nonconformist majority who by that period constituted over three quarters of Welsh churchgoers, in an extremely negative light. What’s more, much of the blame for their alleged deficiencies was apportioned to the Welsh language, as the page image to the right shows.

Listen to historians Ioan Gruffydd, Neil Evans and Hywel Teifi Edwards explain the origins and findings of the ‘Blue Books’ report. This extract is from the BBC Wales radio programme The People of Wales (1999).

Transcript: Audio 2 The Treachery of the Blue Books, BBC Radio Wales, People of Wales (1999)

[ROOSTER CROWS]

[GIRL GIGGLES]

[GIRL GIGGLES]

As Evans points out, what the reports had to say about education in Wales was overshadowed by their claims that the Welsh language led to deceit and sedition, that Welsh women were immoral and that Nonconformist practices were to blame. It is, therefore, hardly surprising that the reports provoked a furious response from Welsh Nonconformists. Even some Welsh Anglicans were outraged. The poet and historian Jane Williams, for example, argued that:

The Reports of the commissioners of enquiry into the state of education in Wales, have done the people of that country a double wrong. They have traduced their national character, and in doing so, they have threatened an infringement upon their manifest social rights, their dearest existing interests, comprised in their ordinary modes of worship and instruction, their local customs, and their mother tongue.

This was an uncompromising start to a systematic refutation of the report’s findings which ran to some 62 pages of text. In 1854, meanwhile, the Baptist bard Robert Jones Derfel coined the phrase ‘treachery of the Blue Books’. This referred to the apocryphal ‘treachery of the long knives’ in which Saxon invaders had supposedly duped and then murdered a group of Welsh chieftains some fifteen hundred years earlier (Morgan, 1984). The speed with which the name stuck suggests that, for many Welsh people, 1847 marked a similarly heinous betrayal.

One lasting consequence of the Blue Books was that they caused the Calvinistic Methodists to join with Wales’s older Nonconformist denominations against what came to be seen as the Anglican enemy. The denominational rivalries that had characterised Nonconformity during the first half of the century seemed unimportant in the face of this vicious Anglican attack. The result was the creation of a new self-consciously Welsh Nonconformist identity in Wales (Morgan, 1984). This is a crucial point because that newly unified sense of Nonconformist solidarity was to prove pivotal in the development of Welsh national aspirations later in the century.

The leading Welsh historian Geraint Jenkins has called the Treachery of the Blue Books ‘a seminal event … which shaped the future of political and cultural life in Wales for several generations’ (2002, p. 213). It hardened support for Nonconformity, led to a revival in religious education initiatives, and reminded the Welsh of the need to trumpet the value of their own culture.