2 A performance of North Indian art music

2.1 An introduction to khyal singing

I now want to move on to explore the first of two case studies of non-Western music-traditions: North Indian art music, also known as Hindustani music. (There are two major art music traditions in South Asia; the other is known as South Indian or Carnatic.) In this section I will take you through a performance of music from this tradition and consider some of the questions posed by Section 1: how is this music put together? To what extent is it composed in advance, thought out, sketched and revised; and to what extent is it created in performance? Is notation used, and if so, how? How might we describe the models for the performance? Which elements are fixed, stable or repetitive? Which elements are variable and determined in performance, and what guides the performer in making the necessary decisions?

I want to cover a lot of these questions through the use of video clips, which include performance footage, demonstrations by the performer, and extracts from a teaching session. Before you watch the video, however, a little background information will be useful.

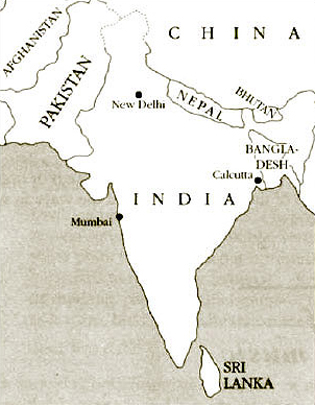

The North Indian art music tradition is practised widely over northern and central India, Pakistan and Bangladesh (see Figure 1). It is also quite well known beyond this native area: you may have heard, or at least heard of, leading performers such as the sitarist Pandit Ravi Shankar. It is an art music tradition, comparable in some respects to that of the West. Court and religious contexts have played an important role in its development, while in the present day its largest audience is to be found among the middle-class population in the towns and cities.

The tradition includes a number of related styles and genres, both vocal and instrumental. The piece featured in the video belongs to a genre called khyal , which is the most commonly heard vocal genre in the tradition (although not by any means the only one). Khyal performances can vary widely in style, textual content, accompaniment and other aspects. (Khyal is a word of Persian origin, meaning literally ‘imagination’ or ‘fancy’.) This section is not intended as a survey of, or introduction to, Indian music as a whole, but is a detailed case study of a single performance. This particular performance is typical of the khyal genre, but not everything that happens here happens in all performances, and conversely some features common in other styles are not represented here.

In order to address the issues which concern us here we will have to go into some of the technicalities of the music and introduce some unfamiliar terminology. You will not need to remember all the details.

Like most performances of North Indian art music, this one features a soloist assisted by a group of accompanists. Typically for khyal, the singer is accompanied by one or more players of the drone-producing lute called tanpura; a drum set called tabla; and a melodic accompanying instrument, in this case a harmonium. The role of these different instruments should become clear in the course of the video. They are essentially at the disposal of the soloist, who instructs the musicians what to play, when and how – although subservient in this respect, they are nevertheless often fine musicians in their own right. (Note that ‘lute’ is used here as a generic term for a class of stringed instrument; technically, it covers those with separate neck and resonator, whose strings run parallel to the sound table.)

The soloist featured in the video clips is Veena Sahasrabuddhe, one of the leading performers of the khyal genre. She will take you through a performance of Rag Rageshree (i.e. a rag or mode, by the name of Rageshree). This piece moves through a number of distinct stages, of which some of the most important are described and demonstrated in the video. In each case, after this explanation, you will see a corresponding extract from the final public performance itself. Finally, the video shows the whole public performance. After you have studied the clips for this case study, you should be familiar, at least in general terms, with the following points.

What is meant by the term rag (mode, melodic framework), and what Rag Rageshree sounds like (we will not, however, be analysing the rag itself in any detail).

What is meant by the term tal (metre, rhythmic cycle), the particular tal used here (called jhaptal), and how it regulates the music.

The way the performance moves through different stages, and the kind of techniques employed by the soloist.

You do not need to memorise all the close detail covered by the video.

Activity 2

In a moment I shall ask you to watch the first sections of the video. Below is a list of the technical terms that are used and explained in the video, laid out in the order in which they occur, so that you can find them easily. For some I have added explanations, which may include additional information not on the video. The others are the names of the stages in the performance I mentioned above.

As you watch the video clips, I want you to use the list of terms for two activities.

Listen out for mention of the terms listed. Pause the video and read my notes as each term is mentioned, to ensure you understand the term and how it is used.

In the places where I have not supplied notes about the stages listed, listen to the explanation that is given on the video, and then pause the video and make your own notes based on the information you have heard, answering the following questions in each case.

(a) Is this stage sung with, or without, drum accompaniment?

(b) Is it sung to a particular text, or if not how is it vocalised?

(c) How would you describe the rhythmic and melodic style (i.e. fast or slow, free or strict, flowing or broken, etc.)?

Now watch the masterclass in the video clips below, following my list of terms and pausing to read and make notes where appropriate.

Veena Sahasrabuddhe sings Rag Rageshree part 1 [8 minutes 40 seconds 23.3MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe sings Rag Rageshree part 2 [9 minutes 54 seconds 26.7MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe sings Rag Rageshree part 3 [4 minutes 6 seconds 11MB]

| barhat | The ‘development’ of a piece, translated loosely here as ‘improvisation’; barhat means, literally, ‘increase; growth’. |

| aroh-avaroh | Basic ascending and descending lines of a rag. |

| alap | |

| sargam | Singing to the abbreviated note names (i.e. instead of a meaningful text); these are, in ascending order, sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha and ni. (Note: you will not hear the name of the fifth note pa in this example. This note is not used in Rag Rageshree, which is hexatonic.) Veena Sahasrabuddhe is using sargam here as a teaching device – she instructs her pupil to repeat the melody ‘in alap’, by which she means singing to the vowel ‘aah’. |

| bandish | |

| tal | Metre, i.e. that which regulates the rhythm. |

| jhaptal | A particular tal. Jhaptal has a ten-beat pattern which is repeated indefinitely. |

| bhav | Mood, emotion, meaning. |

| bol alap | |

| bahlava | |

| tan |

Answer

Here are my notes for the different stages. I hope you got at least some of these points, although you may not have got them all. (I have separated comments on rhythm and melodic style, although these are closely related.)

| alap | sung without drum accompaniment; no text (uses vowel sounds, such as ‘aah’); |

| slow tempo, rhythmically free; | |

| a mixture of long and short phrases; | |

| flowing melody with lots of portamento, melisma, ornamentation etc. | |

| bandish | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| sung to a text; | |

| medium tempo, strict rhythm; | |

| slightly simpler melodic line than alap. | |

| bol alap | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| sung to a text; | |

| medium tempo; | |

| fairly free rhythm. | |

| bahlava | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| medium tempo; | |

| very long, continuous, flowing and rhythmically loose melodic lines. | |

| tan | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| no text (vowels); | |

| fast tempo (especially in the performance footage); | |

| long, continuous melodic lines. |

Activity 3 (Optional)

The next section of video clips shows the complete concert performance of the Rag Rageshree. This section lasts for a total of 25 minutes. If you have time, you will find it useful to watch it now to consolidate your understanding of the characteristics of the different stages of the piece and how they fit together in a single ultimate performance; if you do not have time to watch it all now, come back to it later as a revision exercise.

As you watch, the timings chart in Figure 2 below will help you to keep your bearings and follow what is going on. The captions on the video will also help to identify the stages of the piece.

| Time (mins) | Section | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | 0 | Alap | |

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | Bandish - first part | ||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | Bol alap | ||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | Bahlava | ||

| Part 2 | 8 | ||

| 9 | |||

| 10 | |||

| 11 | Bandish - second part (antara), which emphasizes the upper tonic ('sa') | ||

| 12 | |||

| 13 | Bol alap based on antara (second part of bandish) | ||

| 14 | |||

| 15 | Sargam | ||

| 16 | Bol alap | ||

| 17 | |||

| Part 3 | 18 | Tan | |

| 19 | Bol tan (tan sung to words) | ||

| 20 | |||

| 21 | Tan | ||

| 22 | Tarana (wordless composition set to a different rythmic cycle) | ||

| 23 | |||

| 24 | |||

| 25 |

As you watch, make notes in answer to the following questions. How would you describe the organisation of the performance as a whole? Why do you think these stages come in the order they do?

Veena Sahasrabuddhe performs Rag Rageshree part 1 [7 minutes 40 seconds 20.8 MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe performs Rag Rageshree part 2 [10 minutes 9 seconds 27.7MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe performs Rag Rageshree part 3 [7 minutes 53 seconds 21.5MB]

Answer

You should have noticed certain tendencies as the music moves from one stage to another.

It moves from singing without drum accompaniment to singing with the drums (tabla). As the drums are introduced, the music changes from unmetred to metred (in this tradition, metred sections are always accompanied by drums).

Although the transition is not entirely smooth, the rhythm is much more regular at the end than at the beginning.

Rhythm and tempo are much faster at the end than at the beginning.

We move from singing without text, to with text, and back again.

We may surmise that the different stages occur in this particular order so as to allow (or to bring about) a transition from unmetred, unaccompanied, slow and rhythmically free singing to that which is metred, accompanied, fast and rhythmically strict. Similar processes occur in many other kinds of music – the transition from recitative to aria in opera being one example (the difference here, of course, is that recitative and aria alternate, whereas the shift occurs only once in this Indian performance).

Some additional points that may not have been immediately obvious from the video are to do with the division between which aspects of the music are rehearsed and decided beforehand, and which are directed by Veena Sahasrabuddhe as the concert performance takes place. Basically, the students know from rehearsal that they will be required to sing during refrains of the bandish (which they will have learned), and keep quiet while she is singing alap, bol alap, bahlava and tan. If she wants them to sing up or quieten down in the performance, she gestures appropriately. The pace is set by Veena Sahasrabuddhe too: she indicates this by tapping her hand at the beginning, and when an acceleration is required.