3.2 Parts of the gamelan salendro

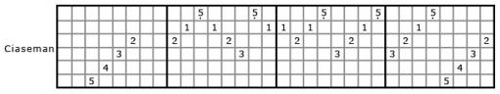

The next set of video sequences feature a type of Sundanese ensemble called gamelan salendro. You will need to know that this music is based on a pentatonic scale, also called salendro. The Sundanese use various methods to describe this scale, the simplest of which is a numerical system in which each note of the scale is assigned a number from 1 to 5. One aspect of the system which may take a bit of getting used to is that the Sundanese assign the numbers to a descending scale, so that pitch 1 is higher than pitch 2 and so on. Similarly confusing is the fact that pitches in the higher octave are indicated by a dot beneath the number, and those in the lower octave by a dot above. The scale is roughly equidistant, with pitch 1 approximately equivalent to A in the Western scale. I have written out the scale in Example 4, below, in staff notation, although in fact you may find it easier to simply follow the number notations than to ‘translate’ everything to and from Western terms. (Note: in a truly equidistant pentatonic scale, each interval would be 2.4 semitones – that is, 240 cents, where one semitone = 100 cents.)

Example 4

Activity 5

Watch the video clip below, which introduces the sights and sounds of the Sundanese gamelan salendro to give you an idea of the music.

Sudanese gamelan part 1 [1 minute 7 seconds 3.01MB]

The next section of the video, headed ‘Instrumental parts for the piece “Bendrong”’, takes you through a few of the simpler instrumental parts for this piece. For the first two instruments featured – the gong and jengglong – I would like you to try to work out the repeated pattern of notes played in each case, and the next activity asks you to do this. You may need to replay the relevant sections of the video several times to complete the activity. As we work through the various instrumental parts you will gradually see how the structure of the piece works, with overlapping instrumental parts working together to build up the overall sound.

Activity 6: The gong part

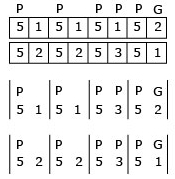

The gong player plays a repeated pattern of notes in an 8-beat cycle, using two gongs called the kempul and gong, as demonstrated and identified on the section of video that you are about to watch.

The grid below shows a space for each beat of the cycle. Watch the video and note whether the kempul (‘P’) or the gong (G) is played on each beat. Leave the space empty if there is a rest with neither instrument playing on a particular beat. Wait for the indication on the screen to help you identify the first beat of the cycle before you begin. (Note: Many Indonesian nouns begin with the prefix ‘ke’ or ‘kern’ so this prefix is generally ignored in abbreviations, to avoid confusion: hence the use of ‘P’ for ‘kempul’.)

![]()

Watch the video clip below featuring the gong player now.

Instrumental part for the bendrong [1 minute 7 seconds 3.10MB]

Answer

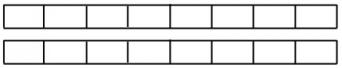

This is how the grid should look. If this is not what you got, watch the video again and try to relate what you see and hear to what is written below.

![]()

Actvity 7: The jengglong part

The jengglong is a set of smaller pitched percussion instruments (sometimes called ‘kettle gongs’). Again you will see that the performer on the video plays them in a set sequence – or, rather, in two alternating sequences, which I would like you to listen to carefully and note down on a grid (see the example below)with two rows for both cycles. (It doesn't matter which one you put first, since they alternate repeatedly.)

As you watch, the video graphics will help you to identify the first beat of the 8-beat cycle, and will also identify the note name in the form of a pitch number for each instalment.

Watch the video clip below demonstrating the jengglong part now, and fill in the appropriate pitch number for each beat in your grid.

Instrumental part for the jengglong [1 minute 48 seconds 4.86MB]

Answer

I hope you got the following answer. (You could have the two lines the other way around; it doesn't matter.) If this is not what you got, watch and listen again, trying to match what is on the video to my answer.

We need next to look at how the gong and jengglong parts fit together. Figure 4 below reproduces the gong player's part laid out above the corresponding beats of the jengglong player's line. The lower part of Figure 4 shows a different way of laying out the same information, incorporating the two parts into the same notation. Notice that the beat divisions have been changed to give 4 sets of 2 beats per line, instead of 8 single beats per line. In effect this is simply a change to give us a neater and less cluttered form of notation. This style of presentation will be helpful as we look at adding yet more instrumental parts to the music.

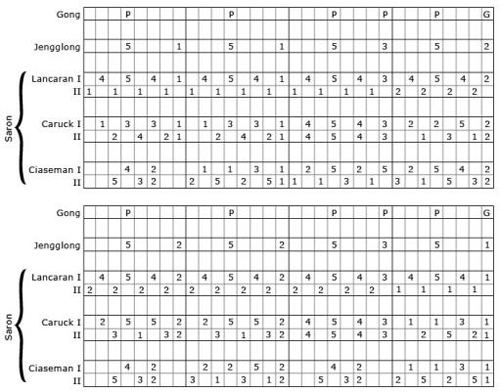

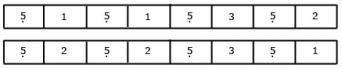

The next instrument I want to consider adding is the saron. The ensemble uses two, identical, saron, which are played as a pair. The principle of the saron is the same as a xylophone, but it is made of metal (hence the generic term ‘metallophone’). In this particular piece of music, ‘Bendrong’, the two players have a choice of three possible patterns that they can play during the phrase that we have been considering. These alternative lines are called lancaran, canuk and ciaseman. It is important to understand that these three options are alternatives and cannot be played simultaneously; the players select just one of them at the relevant point in the piece.

Activity 8

On the next section of the video, first the lancaran line, then the caruk line and the ciaseman line are demonstrated by the saron players. After a short introduction saron I begins alone; saron II joins in later. The note patterns played by each player are supported by the highlighted notation on the screen to help you to follow what is being played, and how the two parts interlock. Watch the video demonstration of the lancaran, caruk and ciaseman below, trying to follow the notation as you watch. Do not worry if you get lost at first, but replay the video clip until you can follow the notation and hear how the two saron parts interlock

Instrumental part for the saron [5 minutes 49 seconds 15.8MB]

The Activity 5 video is a sequence shot at a wayang golek (rod puppet) performance, filmed for this course in Bandung in 1996. It features the gamelan ‘Galura’, directed by Pa Otong Rasta. This section is from the beginning of the all-night performance, and comprises part of an instrumental prelude. We see most of the instruments and musicians of the gamelan salendro in action. (This sequence pieces together shots of various different instalments taken at different times; the music is not continuous.)

The demonstration video clips in Activities 6 and 7 illustrate some of the simpler parts for the piece ‘Bendrong’. It begins with the gong and kempul parts, then the jengglong part. In the Activity 8 video, three possible versions of the saron parts – named lancaran, caruk and ciaseman – are demonstrated, with notations on screen. (Note: The letter ‘c’ is always pronounced ‘ch’ in Sundanese.)

In Figure 5 I've written out in parallel the parts for gong/kempul, jengglong and the three saron alternatives. You should remember that this is not a score: although I have illustrated parts for several players in parallel there are many other parts not shown here, and moreover the lancaran, caruk and ciaseman parts are alternatives to each other and are not played simultaneously.

Activity 9

Now I'd like you to look at the parts written out in Figure 6 and try to work out the following.

How do the lancaran saron parts relate to the jengglong part?

Bearing in mind your answer to (1), now compare the caruk parts with the lancaran parts. What similarities and differences can you spot between them? (A couple of clues: you will find it useful to begin by looking at a fragment of the line, for instance the first four notes of each saron part. Look, too, at the ends of lines and phrases, i.e. those occurring just before the vertical lines.)

How do the ciaseman parts relate to the other parts illustrated here?

Answer

Here are my answers to those questions.

The lancaran saron I is in fact exactly the same as the jengglong part, with the pitch ‘4’ added before each note: thus ‘5 1’ becomes ‘4541’ and so on. Saron II plays a single repeated pitch (either 1 or 2) before each of the saron I notes. These saron II pitches are the same as the jengglong notes that coincide with gong strokes (to check this, look immediately below each ‘G’).

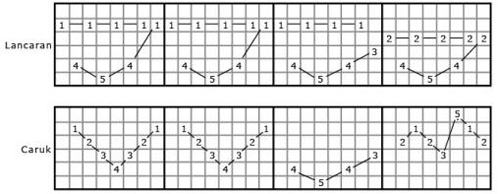

The caruk parts look rather different at first sight, apart from the phrase ‘4543’ which also comes in the lancaran saron I at the same time. Looking at the ends of phrases, however (just before the vertical lines), we see that the notes are identical with both jengglong and lancaran parts. If the similarity is found at the end of each phrase, the difference lies in what happens before this common final pitch. Whereas in lancaran the two saron parts appear to follow a separate logic, in caruk the two only make sense when considered together, because together they form a continuous, conjunct melodic line. Figure 6 indicates how the melody is perceived by the ear: as one continuous line for caruk but as two separate lines for lancaran. Replay the video clips in Activities 6, 7 and 8 if you didn't notice this before.

This is a little harder to identify. Not all the phrase endings are the same, but alternate phrases are. The patterns have something in common with tin-interlocking caruk patterns, but contain more rhythmic and melodic interest, which is clearer if we write the ciaseman part out as in Figure 7.

You should now be getting the hang of some of the basic underlying principles of this music, and of this piece in particular. I'll now elaborate on a few of the principles, starting from a point with which you should already be familiar.

The ends of lines and phrases are particularly important. Thus in this piece we have seen how the first phrase always ends on pitch 1. Examining the rest of the parts we can see that the second phrase ends on a 1, the third on a 3 and so on, giving the pattern shown in Figure 8 below, which records the last note of each phrase. We can call these end-of-phrase notes ‘destination pitches’, while those coinciding with the gong strokes may be termed ‘gong tones’.

If you look back at Figure 5, you can see that the jengglong part simply interpolates the pitch 5 between each of these notes. The lancaran saron I precedes each destination pitch with ‘454…’, while lancaran saron II repeats one of the ‘gong tones’ on the off-beats. In caruk, the two sarons together combine to produce a conjunct melodic line ending on the destination pitch.

Similarly, each of the other instruments has its own idiomatic way (or, like the sarons, choice of ways) of moving to each destination pitch or gong tone. In some cases, the patterns are rather more complex than those we have considered here. Moreover, several instruments can either be played in the kind of simple style illustrated here, or in much more complex and elaborate patterns, depending on the proficiency of the player. The result is that the sound of the group playing together is quite dense and complicated, and yet the underlying structure of the piece is remarkably simple – Sundanese musicians would actually be able to reconstruct all the parts, given only the identity of the two ‘gong tones’.

Although not all Sundanese pieces are this simple in conception, the basic principle that complexity is built on very simple structural foundations certainly does hold true for more complicated pieces. Now we can go on to make some more observations.