5.4 Different analyses of a single theme

There is one question that always arises when beginning an analysis of this sort: ‘Which is the primary tone of the structure?’ Sometimes, as in the preceding example, the melody will contain several pitches that are consonant with the tonic chord. Often it is fairly clear which of these begins a large-scale structural line towards the cadence. Occasionally, though, there are situations where either of two lines is plausible. The thing to remember about all analytical decisions is that there are no hard and fast rights and wrongs, provided that the reduction makes sense as a piece of counterpoint. Experienced analysts can disagree about these things, and their disagreements often suggest that the music itself is rich in different interpretative possibilities.

We will now look at an example which has provoked just such disagreements. In fact, it is one of the most frequently analysed extracts in the whole of the tonal repertoire, perhaps because its apparent simplicity allows analysts the chance to use the piece as a testing-ground for their different analytical formulations.

Activity 18

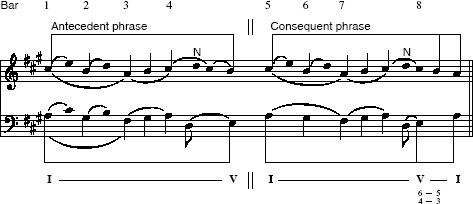

Listen to the opening theme from the first movement of Mozart's Sonata in A, K331 (Extract 11), following the score extract given as Example 27. How would you describe the structure of this theme?

Click to listen to Extract 11

Discussion

This sonata is famous for its quirkiness. The first movement is a set of variations on the theme whose first half is given in Example 27, rather than the usual sonata-form Allegro; and the last movement is the celebrated Rondo alla Turca. Once again, though, Example 27 is a clear-cut instance of an interrupted structure (I–V in the first phrase, I–V–I in the second).

The sequential patterns of the musical surface certainly encourage us to hear a descending linear shape. But which line should be identified as the middleground framework?

The first note of the piece (C#) is the beginning of a downward line, moving at one bar's duration: C# (bar 1) – B (bar 2) – A (bar 3). This line gains emphasis by beginning on the first beat of each bar. However, there is another linear shape running in parallel thirds above this: E (bar 1) – D (bar 2) – C# (bar 3). This also has claims to be the main middleground line, since it is higher, and therefore more prominent, than the inner line. In fact, the two lines can be analysed as two unfolded voices, a ‘treble’ and an ‘alto’, running in parallel.

I don't think it really matters which of these descriptions of the structure you prefer; there are merits to each. Any analysis, of course, must, however, be consistent. We are going to look at graphs which show three equally legitimate possibilities.

Activity 19

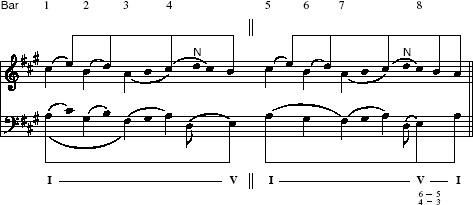

Compare each of the three graphs in Examples 28, 29 and 30 in turn with the score extract (Example 27). Listen to the theme again (Extract 11) as you work through them. What aspects of the theme does each graph emphasise in its analysis of the structure of the extract?

Click to listen to Extract 11

Discussion

The first graph (Example 28) brings out the third degree of the scale (C#) as the primary tone of a large interrupted line. Arguably, though, it does not really do justice to the upper pattern E–D–C#.

The graphs in Examples 29 and 30 give more weight to the upper line, but locate the main structural notes in different places. Example 29 gives more emphasis to the first descending pattern in bar 1–3. Example 30, on the other hand, analyses this pattern as belonging to a subsidiary level, nesting inside the most important middleground line E–D–C#–B, that comes to rest on an imperfect cadence at the end of bar 4.

Example 29 reduces away the 6/4 chord on the second beat of bar 4, adhering to the principle that this sort of harmony is not truly a version of the tonic chord, but rather needs to resolve to the dominant 5/3. It is therefore less important, structurally, than the dominant (the B over chord V at the end of bar 4). Example 30, on the other hand, places a main note of the descending line (the C#) over a 6/4 chord. This is arguably acceptable, however, since the 6/4 chord still resolves to this following 5/3 chord.

It probably won't surprise you to learn that all three of these graphs have been adapted from published analyses by different experts. The seemingly curious placing of a structural note over a 6/4 harmony was, in fact, the version preferred by Schenker himself. [Example 28 corresponds in most respects to an analysis by the American scholars Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983) and Example 29 follows the view of structural movement taken by Forte and Gilbert (1982). Example 30 follows Schenker's own analysis (1979).] But again it has to be emphasised that we are in the domain of personal taste, and that you should always let your hearing be the judge in such cases.