3 Emotions as bodily feelings

3.1 William James

In 1890, the philosopher and psychologist William James published his influential work The Principles of Psychology. The book included a chapter on the emotions, in which James advanced a bold new thesis about the nature of the emotions. James's thesis has had an enormous influence on subsequent debate.

Reading 1 is a short extract from James's chapter on the emotions. In the passage that precedes this extract, James castigates earlier psychologists who have written on the subject. According to James, these writers have concentrated on providing minute descriptions of particular types of emotion, without offering any account of emotion in general. In contrast, James proposes to offer a general theory, from which some universal principles can be derived. James presents his account as hypothetical – that is, as a speculative account, that draws on everyday experience, but which is still in need of proper empirical proof. However, he also contrasts his account with what he takes to be our ordinary conception of emotion, implying that our ordinary conception needs to be modified in certain ways.

James begins by discussing what he terms the ‘coarser’ emotions: these are the emotions that nearly everyone believes to involve recognisable bodily changes. The examples he gives include grief, rage and fear. Later in the chapter, he will turn his attention to the ‘subtler’ emotions – the emotions elicited by the aesthetic properties of a work of art, the intellectual qualities of a mathematical proof, or the moral qualities of another person.

Activity 5

Read the extract from James's chapter (Reading 1).

Click to open William James's chapter [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

What does James believe to be our ‘natural way of thinking’ about the emotions?

What, in contrast, does he claim emotions to be?

What reason does James give for supposing that his thesis is correct?

Note: It would be easy to answer these questions by finding the relevant sentences in the extract and underlining them (particularly easy in this case, since James italicises crucial sentences). But once you have identified James's answers to these questions, try to express what he is saying in your own words, or draw a diagram.

Discussion

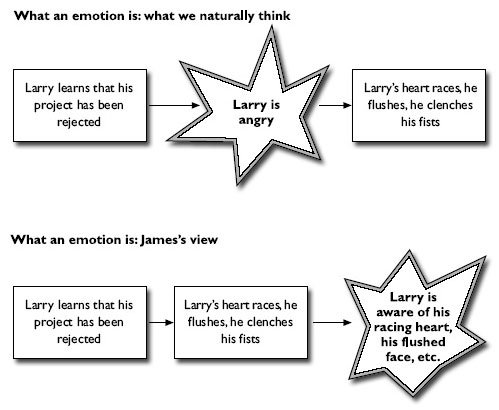

According to James, we naturally think that an emotion is a state which is caused by our perception of some eliciting event and itself causes certain bodily changes.

According to James, what we naturally think is incorrect: it would be more accurate to say that our perception of some eliciting event causes bodily changes which we then feel: our feeling those bodily changes is an emotion. In other words, emotions are bodily feelings, in the sense defined earlier. (See Figure 1.)

James suggests that his theory is supported by the fact that we never find an emotion occurring without the subject feeling bodily changes. This, James suggests, is the distinction between feeling fear and dispassionately judging that the situation is dangerous.

James presents his account as a corrective to our ordinary conception of emotion. He believes that empirical enquiry will reveal our ordinary conception to be misplaced, and presents an alternative view that, be believes, is more likely to fit the facts. Nevertheless, there are some ways in which James's account could be viewed as endorsing the intuitive picture of emotion that I set out earlier on. In particular, James emphasises the bodily nature of emotions: it is their bodily nature that differentiates them from dispassionate judgements. However, James does not claim that emotions are located in the body: on James's view, emotions belong in the mind – they are the feelings produced by bodily changes, not the bodily changes themselves.

James goes on to suggest that everything he has said about the ‘coarser’ emotions will be true of the ‘subtler’ ones too: even in the case of the subtler emotions it is impossible to regard the subject's response as an emotional one unless we are assuming that they are feeling bodily changes of the required kind.

In all cases of intellectual or moral rapture we find that, unless there be coupled a bodily reverberation of some kind with the mere thought of the object and cognition of its quality; unless we actually laugh at the neatness of the demonstration or witticism; unless we thrill at the case of justice, or tingle at the act of magnanimity; our state of mind can hardly be called emotional at all. It is in fact a mere intellectual perception of how certain things are to be called – neat, right, witty, generous, and the like.

(James 1950, pp. 470–1)