2.2 The source of an utterance's meaning: the words used or the speaker's mind?

How are we able to use language to communicate knowledge? Locke's question, introduced in section 1, was recast as the obligation to spell out what ‘meaning’ amounts to as it figures within a simple theory of communication, repeated here:

The simple theory of communication

The successful communication of knowledge about the world is possible because speakers are able to produce utterances with a specific meaning, and recognition of that meaning by an audience enables them to appreciate what the speaker intends to communicate.

This theory is, we saw, only genuinely explanatory if we can supplement it with a non-vacuous statement of what it is for an utterance to have the meaning it does. Our task in this section will be to explore ways of doing this.

There are two different and potentially incompatible approaches to carrying out this task, distinguished according to what they take as the source of an utterance's meaning. According to one view, the source is the meaning of the expressions uttered according to the language to which they belong. If a speaker utters the sentence, ‘The German economy is bouncing back’, what the utterance means is that the German economy is bouncing back. On this first view, it means this because that is what these words mean in English. If the speaker had unusual ideas about what the words ‘German’ and ‘economy’ mean – for example, that they mean what we ordinarily mean by ‘folding’ and ‘bed’ respectively – this would not (on this first view) change the meaning of the utterance. The speaker would still have said that the German economy is bouncing back, not that the folding bed is bouncing back.

Many find this thought intuitively appealing. To others, it seems unnecessarily prescriptive. Why, they ask, can we not use language in ways of our own choosing? If someone wants to use ‘jealous of’ to mean envious of rather than possessive of (its traditional or ‘proper’ meaning), then why shouldn't they? This second view treats the speaker's mental states as the source of the meaning of the utterances they produce. Supporters of the first view often respond to the liberal, speaker-centred perspective by pointing to the disastrous consequences of treating the actual speaker rather than the words the speaker uses as the arbiter of an utterance's meaning. They are fond of alluding to Humpty Dumpty (as he figures in Lewis Carroll's Alice through the looking-glass rather than as he figures in the nursery rhyme) to make their point. Below is a passage from the book in which Humpty proclaims his right to mean whatever he wishes by the words he uses.

‘As I was saying [said Humpty Dumpty], that seems to be done right – though I haven't time to look it over thoroughly just now – and that shows that there are three hundred and sixty-four days when you might get un-birthday presents –’

‘Certainly,’ said Alice.

‘And only one for birthday presents, you know. There's glory for you!’

‘I don't know what you mean by “glory”,’ Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. ‘Of course you don't – till I tell you. I meant “there's a nice knock-down argument for you!”’

‘But “glory” doesn't mean “a nice knock-down argument”,’ Alice objected.

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master – that's all.’

Alice was too much puzzled to say anything; so after a minute Humpty Dumpty began again. ‘They've a temper, some of them – particularly verbs: they're the proudest – adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs – however, I can manage the whole lot of them! Impenetrability! That's what I say!’

‘Would you tell me please,’ said Alice, ‘what that means?’

‘Now you talk like a reasonable child,’ said Humpty Dumpty, looking very much pleased. ‘I meant by “impenetrability” that we've had enough of that subject, and it would be just as well if you'd mention what you mean to do next, as I suppose you don't mean to stop here all the rest of your life.’

‘That's a great deal to make one word mean,’ Alice said in a thoughtful tone.

‘When I make a word do a lot of work like that,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘I always pay it extra.’

‘Oh!’ said Alice.

(Carroll 1893, 113–15)

We can distil from this dialogue a claim – call it Humpty's thesis – regarding the extent to which what we mean is under our own control rather than dependent on the meaning of the words used, where this latter is independent of our wishes:

Humpty's thesis

What we mean when we utter a word or sentence is under our own control; we can mean whatever we want and choose.

Though it is difficult to see exactly why, Humpty's thesis seems deeply misguided. Grice's theory, to which I now turn, sees the mental states of the speaker as the primary source of the meaning possessed by the utterances the speaker produces. He even claims that the relevant mental states are the speaker's intentions. This sounds as if he is just providing a ‘Humpty-Dumpty’ theory according to which what we mean is up to us. Whether this unflattering comparison can be made to stick is something to consider after seeing the details of his influential theory.

Activity 1

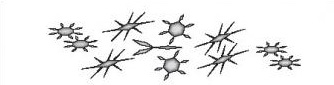

We will be examining a position according to which the meaning of utterances is inherited from the content of the speaker's mental states. Having just read Humpty's embarrassingly extreme statement of this view, you may be deeply unsympathetic to that idea. So, to counterbalance your sympathies, consider a reason to be suspicious of views at the opposite extreme, which treat the meaning of utterances as entirely independent of mental states. Suppose some rocks are found arranged in a pattern on the dusty surface of Mars, as below:

The rock pattern could be the equivalent in some alien language of a piece of clumsy but meaningful handwriting. Alternatively it could be a meaningless cluster of tiny fallen meteorites, any discernable pattern in it being a random accident. What would make you treat this pattern of rocks as a meaningful utterance – not a verbal utterance obviously, but an utterance in the same sense that a written letter is an utterance?

Discussion

Arguably, in order to be meaningful the cluster would have to be judged as having been produced by some intelligence, perhaps with the intention of communicating with another intelligent being, or with us, or with God, or (as in a diary or a doodle or an arithmetical calculation) with itself. Considered merely as an unintended and accidental pattern in the dust on the Martian surface, it has no meaning whatsoever. If by outlandish chance a cluster of meteorites fell into a pattern that spelled out the English sentence ‘Lo, Earthlings!’, it would still not mean anything – though in that case we could be excused for incorrectly reading meaning into a meaningless event. This is a reason of sorts for suspecting that the meaning of utterances is dependent on the psychological states, perhaps even the intentions, of the producer of the utterance.