You have probably seen those Dutch paintings of gloomy skulls, hourglasses and hurly-burly tables. These vanitas (‘vanity’) paintings were popular and sought-after in 17th century Dutch society. They reminded their viewers of the shortness and unpredictability of life, and the futility of pursuing worldly ambitions.

They spoke to a mostly-Protestant audience surrounded by the temptations of riches. Compared to the iconography of saints and the Virgin Mary in Roman Catholicism, the dark and intricate images emphasise austere, studious self-reflection. All this is deliberate.

During the late 16th and 17th centuries, the small Dutch Republic became one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Developments in art, science and trade flourished. But within a century it nearly collapsed through religious divisions, geopolitical rivalry and rampant inequality. Why was that – and what lessons does the example of the “Golden Age” hold today?

The Night Watch by Rembrandt (1642).

The Night Watch by Rembrandt (1642).

The Dutch revolt

The Low Countries – incorporating modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and northern France – had risen up in revolt against Spanish rule in 1566. After a long and protracted war of independence, the northern Dutch United Provinces formally gained their independence in 1648.

From the outset, the majority-Protestant Dutch Republic was surrounded by powerful and mostly Catholic enemies. Spanish control of the Mediterranean meant that in order to trade and prosper, the Dutch had to establish new trading routes and partners. They undertook experimental and dangerous voyages around the Cape to reach India, China, Japan and modern Indonesia.

The Dutch East India Company factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Mughal Bengal. Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665.

The Dutch East India Company factory in Hugli-Chuchura, Mughal Bengal. Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665.

The Dutch East India Company was established in 1602 to capitalise these risky but lucrative missions. It brought back tea and coffee, spices, ceramics and silk. It soon dominated European trade with Japan, China, Mughal India and the Far East. Meanwhile the Dutch West India Company came to briefly dominate the slave plantations of Brazil and Surinam. Through slavery, piracy and a new concept of free trade, the Netherlands was transformed by wealth and luxury goods. Stock markets boomed and bust, like the “Tulip Mania” of 1637.

Amsterdam freedoms

Beneath the splendour, the Netherlands sat on several contradictions. On the surface it was one of the most liberal in the world. Scientists and philosophers were given an unusual freedom to research and publish. While Descartes redefined what it meant to be a human being (“I think therefore I am”), scientists like Christiaan Huygens and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek invented telescopes and microscopes that made visible new worlds of experience.

There was also an unusual degree of freedom of worship. Persecuted Jews from across Europe were given refuge in Amsterdam, while Non-Conformist Christian groups with radical views about Jesus Christ’s mortality could meet and publish.

But beneath the apparent religious freedoms was a powerful Calvinist public church that was lobbying for heavy restrictions on philosophical research and a crackdown on dissenting views. In the cities, a wealthy merchant class-controlled trade and politics, and the country’s “Golden Age” was far from evenly distributed. And while in theory the relatively new country was a republic, in practice its head of state had at times been the first-born son of the House of Orange, a powerful and popular aristocratic family that had led military efforts towards independence.

By the late 1660s, the Dutch Republic had become roiled by costly and disastrous wars with England and a growing public backlash against its liberal, republican rulers and their values. Into the fray came a remarkable book – and a remarkable author – which aimed to defuse the situation and protect the fragile republic.

The Theological-Political Treatise

Anonymous portrait of Spinoza, c. 1665.

Baruch Spinoza was born in Amsterdam in 1632. From a young age he was intellectually precocious, and after being expelled from his Jewish community because of his unconventional ideas about God, he worked as a lens-grinder while quietly developing his own philosophical system.

Anonymous portrait of Spinoza, c. 1665.

Baruch Spinoza was born in Amsterdam in 1632. From a young age he was intellectually precocious, and after being expelled from his Jewish community because of his unconventional ideas about God, he worked as a lens-grinder while quietly developing his own philosophical system.

Worried by the situation, in 1670 Spinoza anonymously published the Theological-Political Treatise (1670).

In it, Spinoza argued that the Calvinists had acquired too much power over politics. Using his extensive knowledge of Hebrew and the Old Testament, Spinoza argued that all the teachings of the prophets, from Moses to Jesus Christ, could be reduced to simple lessons to live peacefully and cooperatively together. Miracles or special claims to being God’s chosen people were false – all human beings are equal by Nature, which is governed by universal laws that science and philosophy can discover. Everything else is a matter of private conscience.

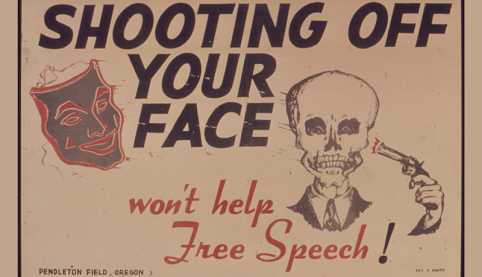

The TTP immediately caused a scandal, with one contemporary describing it as a book ‘forged in hell by the Devil himself’. Copies were impounded and burnt. But its arguments about democracy, freedom of speech and religious toleration would transform Europe, influencing the late-18th century Enlightenment, Romanticism and theorists of radical democracy today.

Watch a roundtable with Mogens Laerke, Martin Saar and Dan Taylor, plus more videos from an event webpage here.

Watch a video below by Hasana Sharp of McGill University, as she discusses “I Dare Not Utter a Word”: Truth, Lies, and Political Violence in Spinoza.

Discover more articles like this

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews