2.4 Berliner

Emile Berliner (1851–1929) became interested in recording sound through studying a device called the phonoautograph. This apparatus inscribed sound vibrations as a lateral trace onto lamp-blacked paper using a diaphragm and stylus. Berliner thought that this lateral motion could offer superior recording quality to Edison’s vertical method. He also decided to use a disc, which he called a plate, which was rotated at a fixed speed, rather than a cylinder as the recording medium. This overall design was sufficiently different from the phonograph to allow it to be patented in 1887 using the name gramophone.

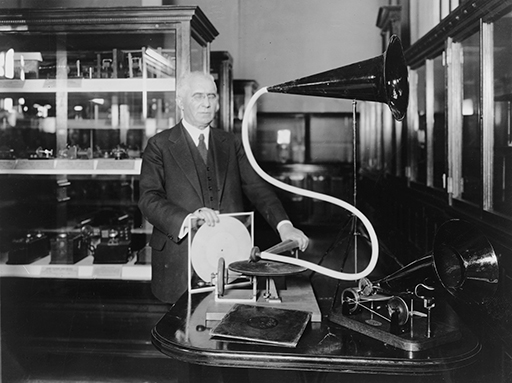

Berliner made his plates from a tough rubber-based compound called vulcanite, allowing for a deep groove. This deep groove allowed cheap, replaceable steel needles to be used in place of the delicate jewel stylus found in the cylinder machines. This made the gramophone (Figure 5) cheaper to manufacture than the competition. In 1894 Berliner’s United States Gramophone Company released their first single-sided 7 inch (18 cm) diameter disc.

An important point to note is that unlike its rivals, the gramophone had no means of recording sounds – it was designed from the outset only to play back pre-recorded sounds. This demonstrated a high degree of faith by Berliner that people would be happy just to listen to sounds (and music in particular) in their own homes.

Activity 3

Listen to these two tracks. The first track contains an original recording by Emile Berliner made in 1889 and this is followed in the second track by a repeat of Edison’s recording that you have heard already. Remember that this recording of Edison was made in 1927, 50 years after his first attempt. How do you think Berliner’s recording compares with that of Edison? How would you describe the differences?

Discussion

The recording by Berliner was taken from an original 5 inch (13 cm) diameter vulcanite disc. I think you will agree that the reproduction is poor compared with the recording of Edison; the distortion and noise make the words spoken by the voice barely audible. Edison’s recording gives the voice much greater clarity. Even so, it still suffers from a limited frequency range and the noise which is concomitant with the level of technology with which it was produced.

Berliner was aware that Edison had problems duplicating cylinders. Initially copies were made from a master cylinder using a mechanical engraving process. Unfortunately this method caused the master cylinder to wear out after making just a few copies, so performers had to be asked to record several masters to ensure enough cylinders could be duplicated. An improved recording system allowed multiple master cylinders to be made by feeding several recording phonographs from one horn, but the cylinder-copying process was still far from satisfactory.

It took Berliner six years to perfect disc duplication but it was time well spent, for the principles are still used today to manufacture CDs.

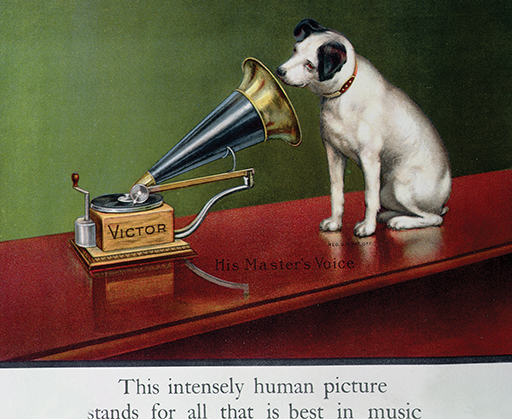

The owners of the original hand-cranked gramophones were instructed that the standard velocity for ‘seven-inch plates’ was about 70 revolutions per minute. The owner was also warned that failure to turn the plate at the correct speed would lead to a lowering of the pitch if turned too slow, or a raising of the pitch if turned too fast. It is doubtful if true reproduction of the recorded sound was ever achieved by the owners of these machines! A better power source was needed and as electric motors were far too costly, a suitably powerful and inexpensive clockwork motor was used. It was designed and built by Eldridge Johnson (1867–1945), who would later form Victor Talking Machines and Victor Records, which would become RCA-Victor. The clockwork motor proved an immediate success, Christmas 1896 seeing the Berliner Gramophone Company of Washington, DC ahead of all the competition, with the factory being unable to keep up with the demand. By mid-1897 the ‘Improved Gramophone’, with a new Johnson-designed motor and soundbox, was launched. This model was destined to become one of the most familiar icons in the recorded music field for it was immortalised, along with a small dog called Nipper, in a painting by Francis Barraud (Figure 6). The painting became the trademark of the HMV (His Master’s Voice) Company in Europe and Victor Records in the USA.

The recording and playback speed would ultimately be standardised at 78 revolutions per minute (rpm), although recording speeds varied from under 70 to over 80 rpm. To cater for these differences a speed controller was fitted to most gramophones.

Disc diameters also varied, but 7-inch (18 cm) playing for two minutes, 10-inch (25 cm) playing for three minutes, and eventually 12-inch (30 cm) playing for up to five minutes became standard. Eventually recordings were put on both sides of the disc – known then, as now, as the A and B sides – offering better value and greater convenience to users.