4.1 Rilke and the Archaic Torso of Apollo

In the English Literature section, you examined in some depth the ways in which Byron’s poetry captured his experience of visiting Rome in the early nineteenth century. To expand your sense of how poetry and creative writing can take a cue from the material remains of the ancient world, you’re now going to turn to another example: poetry written about a fragment of Greek sculpture. Although this takes us to another part of the ancient world, and is not specifically about the experience of travelling to an ancient site itself, nevertheless it shows us that the creative potential of a cultural encounter with antiquity is by no means limited to the phenomenon of the Grand Tour itself.

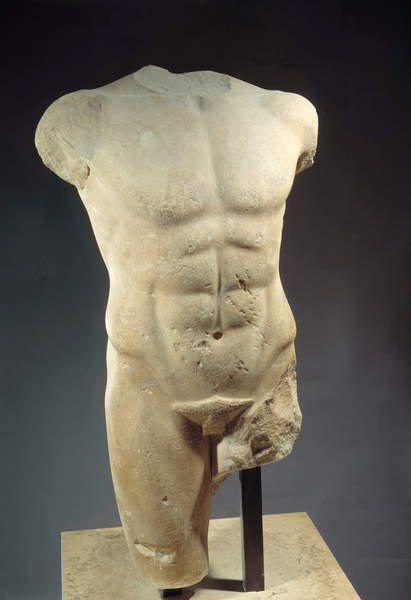

The artefact in question is a sculptural fragment of a male statue (Figure 16), of which not much more than the torso remains. It has been dated to the early fifth century BCE, and was discovered in 1872. It is now on display in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

A few decades after its discovery, the Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) wrote a very successful poem in response to viewing this statue: ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’ is a sonnet (here translated from the German by Stephen Mitchell). It first appeared in Rilke’s Neue Gedichte (1908) (New Poems), volume 2. The word ‘archaic’ in the title refers to the period of Greek history in which Rilke imagines the statue belonging (a period usually considered to end c.480 BCE), and he also identifies it (though this can only be a guess) with Apollo, the god associated with the sun, music, poetry and truth. One critic has written about Rilke’s ‘fascination with the material traces of the past’ (Waters, 2010, p. 71), but for our purposes the thing you need to know about Rilke is that he worked as secretary to the sculptor Rodin in Paris from 1905–6 and began to write poetry that responded to the objects around him. He was a poet who ‘wanted to write poems with the same kind of muscularity and physical presence as Rodin’s sculptures’ (Doty, 2014).

Activity 9

Now read Rilke’s poem. As you read, think about how Rilke builds up a description of the torso and make some notes about how he uses imagery to animate the sculpture that he is describing.

Archaic Torso of Apollo

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

Discussion

While you may have noticed different things, you may have been struck immediately by how Rilke talks about what is absent (e.g. the head, the eyes), as well as what is present (the torso) and, as is often the case for writers, he imagines, on the basis of what he sees, the ‘inside’ of the representation, that is, what is not on outward display. Outwardly, we have a fragmented piece of sculpture, albeit a finely made one, but the sculpture in the poem is animated by human drives and impulses (towards pleasure and procreation). The statue is ‘lit up’ from the inside and gleams. What is particularly interesting is the way that the poet turns the tables on the viewer who is gazing at the statue so that it appears that it’s the other way around: the viewer is being watched and must respond by making changes to their life. For a writer like Rilke, art is a means of transforming apparently inert matter into something more dynamic and creating a bridge between past and present, viewer and viewed, object and subject.