4 The portrait tradition: methodology

4.1 Facial expression

Facial expression was considered the most crucial element to success in painted portraiture. It was the vehicle through which intangible qualities of mind and soul were conveyed. In painting the idea was to achieve the ideal expression, a synthesis of character and the spiritual essence of being. Although cameras could portray any number of expressions with relative ease – an advantage of the machine over manual practice – early portrait photographers continued to believe in the ideal expression which could epitomize an individual's character and experience.

Dedicated photographers attempted some originality of expression in portraiture and art work intended for exhibition. Commercial photographers, however, adopted the convention of a formal, unsmiling expression. You may be familiar with the standard explanations for the absence of smiles and laughter in Victorian portraiture, namely long exposure times, which meant that sitters could not hold a smile, or the theory about concealing bad teeth. Let's see if these explanations hold water.

Activity 4

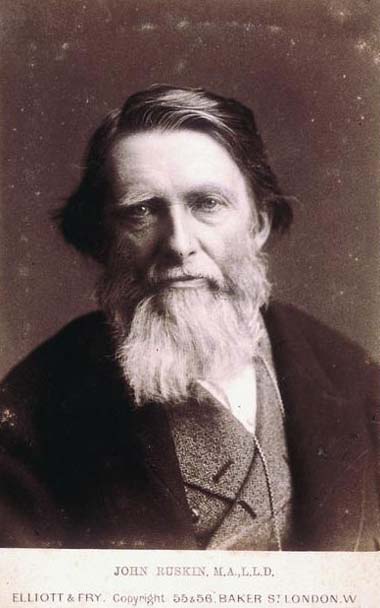

Look carefully at Image 13, a portrait of the artist, writer and critic John Ruskin. What qualities do you read into his facial expression? It may be helpful here to compare Ruskin with the smiling expressions (‘Say cheese!’) we adopt in front of the camera today. Note down your ideas; we shall return to them later.

Cartes de visite and cabinet portraits of celebrities – royalty, politicians, church ministers, actors and writers, for example – retailed in print shops, fancy goods outlets, stationers’ and photographers’ studios in the 19th century. They were placed in family albums alongside the portraits of relatives. Many of these celebrity portraits carried no identification of the sitter. From 1862, manufacturers could attempt to protect their rights in the work by registering the image at Stationers’ Hall. The word ‘Copyright’ on the mount can indicate that the image was so registered though this is not always the case. Photographers paid a fee and filled in a form which usually (though not always) carried a copy of the image. These copyright records are held today in the Public Record Office at Kew. This splendid resource is unfortunately difficult to access as it is organized only by date of registration.

Activity 5

Click on 'View document' below to open and read 'The anatomy of expression in painting' by Charles Bell, 'The photograph and artistic colouring' by Alfred H. Wall and 'The studio and what to do in it' by H. P. Robinson. These are extracts from 19th-century manuals and articles giving artists and photographers advice on expression in portraiture. Answer the question below.

View document [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

What qualities did laughter and smiling convey to artists and photographers in the 19th century?

Answer

Bell (Item 31) is very clear about the expression he regards as unacceptable. Broad laughter was vulgar and ludicrous. Smiles could convey various meanings. But the preferred expression, variously described as ‘a certain mobility of the features’ and ‘an evanescent illumination of the countenance’ was ‘more enchanting than the dimpled cheek’.

For Wall (Item 32), a smile, once fixed and permanent in a photograph, appeared as a ‘piece of affectation’ or ‘mere grin’. And grinning was objectionable.

Robinson, too (Item 33), regards broad laughter as intolerable when fixed in a photograph, though beautiful in life because of its transience. He quotes at some length the attitudes of the sculptor John Gibson. This is a way of giving his own preferences added authority. Gibson regards smiles as frivolous and favours a serious and calm expression as it represents ‘men thinking, and women tranquil’. Gibson's distinction between the sexes reveals evidence of sexual stereotyping. This is extended in Robinson's approval of a ‘cheerful’ expression for ladies and a happy expression for children. The notable absence of any reference to men in this context suggests that the Victorians regarded smiles as frivolous and lightweight.

Activity 6

Now return to your notes from Activity 4 and compare your ideas of the qualities you read into Ruskin's expression with the qualities that Victorians might have read into it.

Answer

Serious expressions convey to our generation the idea that a person is stern, miserable, morose or gloomy. In contrast we read into the smiles of our contemporaries notions of success, confidence, warmth of personality, friendliness and fun; in short, positive values. The Victorians would have approved of Ruskin's expression as concealing any public display of emotion. It appears calm, controlled and dignified, qualities indicative of a thoughtful mind, a man who took himself seriously and invited others to do likewise.

The interpretations placed on expression, then, are relative to culture and date. We have returned to the issue of context which was so vital to our reading of written records.

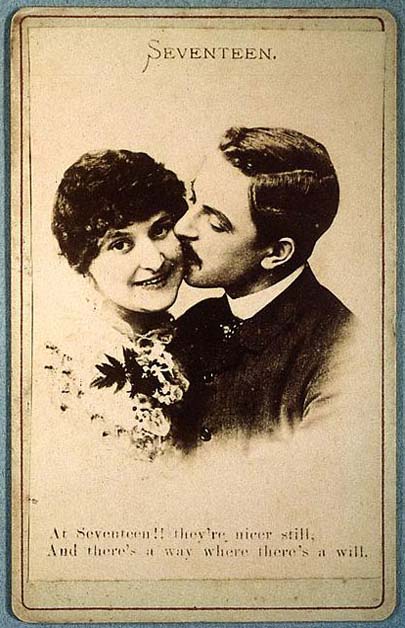

Smiles could certainly be achieved in Victorian portrait photography, but were normally restricted to commercial or humorous photographs for the retail trade. Actresses frequently smiled in their portraits but as their social status was equivocal, the smile in this context could be interpreted as availability or invitation. The ‘respectable’ distanced themselves from such connotations in their family portraits.

So I think we can reasonably argue that the absence of smiles in 19th-century portrait photography was not due to technical considerations. Indeed, when the gelatine dry plate succeeded the collodion wet plate negative in the 1880s, exposure times were reduced to fractions of a second yet we do not witness any immediate or widespread outburst of smiles and laughter in the family album.