2.3 Moving through time …

Starting with our artefact, the feeding bottle, and working backwards, you can see that the whole area of childbirth, health and infant care produces many potential areas for research. We are led to consider issues of class, consumption, gender roles, professionalisation, knowledge transmission, custom and culture. If you were to continue researching you would need to make choices as to what topic and evidence to focus on.

Moving forward from the date of our bottle into the late nineteenth century we find the idea that ‘breast is best’ was very much debated. Influenced by the ideas of Darwin and population ‘improvement’, the medical profession, the British state and local authorities were all concerned with the health and mortality of the poorest babies. In the 1880s and 1890s, widespread reporting and the study of poor families, particularly in the largest urban slums, produced panic about the health of the next generation and dubious concepts of moral, physical and urban ‘degeneracy’.

In efforts to improve infant mortality rates, local authorities in large industrial cities began to offer mother and baby health services including health visitors, clinics and milk dispensaries in the 1890s and 1900s. Bottle feeding had been discouraged through the nineteenth century as milk, like much food in Victorian towns and cities, could be adulterated and laden with disease bacteria, so the introduction of safe powdered milk was a breakthrough. Local municipal and health authorities focused on supplying babies where the mother was malnourished and in poor health, hoping to break a perceived legacy of intergenerational poor health and urban degeneracy. The historian Valerie Fildes (1998) has shown how important such local authority action was to infant health and lower infant mortality, particularly improvements in health education and in supplying milk to mothers and babies.

Activity 6

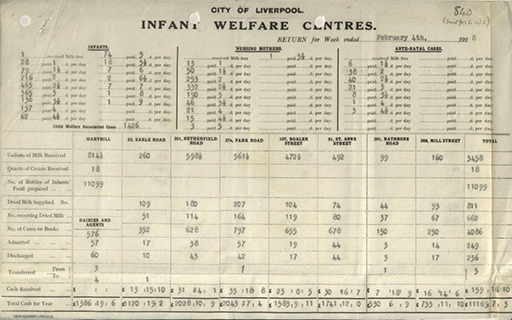

In the decades before national health services (1945 UK, 1957 Ireland) locally organised mother and infant services were vital. Look at this evidence from inter-war Liverpool’s Infant Welfare Centres. Do not worry too much about trying to take it all in at once; just focus on listing a few points. Who was being fed? What products were offered?

Tip: If you have time, you could try to see differences between the centres. What type of tentative theory might you develop as to their locations?

Discussion

There is a lot that you can glean from a document like this, but it also raises further questions too and you might feel you need other information to cross-check and truly make sense of it.

Some brief aspects that you might have listed include:

- In February 1928, Liverpool’s local authority was feeding 1,426 infants, 934 nursing mothers and 117 pregnant women.

- Only one infant received this service for free; these were subsidised, apparently means-tested, paid-for services.

- Mothers and infants received various milk products in the form of fresh milk, dried milk, cream or prepared and filled babies’ bottles.

- There are clear differences between the centres in the numbers of cases they are handling and the products they are supplying. The Harthill Welfare Centre seems to operate as a bottling and distribution point for infant feeding.

From this point you need more evidence, for example you might theorise that the Netherfield Road Centre was in a more deprived area than the Rathbone Road Centre, but it may just have been a larger centre or covered a larger or more populous catchment. You can see that Liverpool was spending significant amounts of money on this provision – over £11,000 so far that year (calendar, civic or financial?), but you would need more information (primary sources) to draw any conclusions.

It would also help to know about Liverpool’s birth rate and birth statistics to understand how significant this provision was and what proportion of the population it reached. Remember you have only seen a snapshot of a single week. Here you can see how the historian’s need for information grows; you might even like a street map of interwar Liverpool to locate these welfare centres!