1.2 History

In the early part of the first millennium AD, the predominant languages in the British Isles were Celtic. Britain was dominated by P-Celtic or Brythonic, whose modern descendants are Welsh, Cornish and Breton, whereas the population of Ireland predominantly spoke Q-Celtic or Goidelic, from which Scottish Gaelic, Irish Gaelic and Manx Gaelic are derived. It is generally thought that immigration from Ireland brought Gaelic into parts of Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man and western Scotland, but the language survived in the long term only in Scotland and Man.

In the days before mechanised transport, it was the sea, rather than the land, that provided the easiest means of travel for people and goods and, given their close maritime connections, it was natural that regular communication took place between north-eastern Ireland and western Scotland.

By around 500 AD the small kingdom of Dál Riata1 had expanded from Ulster to include a large swathe of western Scotland. This maritime region was populated by people known to Latin writers as Scotti, whose language was Gaelic. In Scotland their country, which eventually stretched from the Mull of Kintyre to as far north as Loch Broom, was referred to as Airer Goídel (the coastline of the Gaels), Earra-Ghàidheal in modern Gaelic, Argyll in its anglicised form.

The Scots came across other linguistic groups as they extended their influence across Scotland. The dominant people in the north were the Picts, who are thought largely to have spoken a P-Celtic language. Across the south were the Cumbric people, also speaking a P-Celtic tongue and, in the south-east, the Anglians, speakers of a Germanic tongue, which was the ancestor of modern Scots and English. For the next 600 years or so Gaelic was to expand at the expense of other languages, except in the far north and north-west, where it came under pressure from Norse from the 9th century onwards.

The church of St Columba (521-97), whose Gaelic name Colm Cille (Calum Cille in today’s vernacular) means ‘dove of the church’, played an important role in the Gaelic expansion.

From the monastery of Iona, established by Columba in 563, daughter monasteries were established and prosyletisation by Scottish and Pictish missionaries took Christianity across the country, founding institutions in which the vernacular tongue appears, more and more, to have been Gaelic.

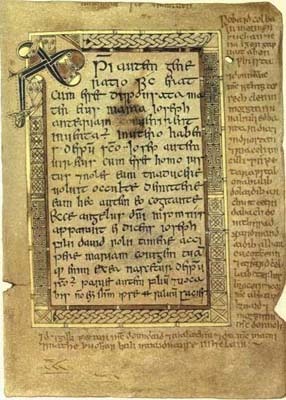

For example, the marginal notes in the Book of Deer2, written at the monastery of Deer in lowland Aberdeenshire in the 12th century, and which claim the institution was founded directly from Iona, are written in Gaelic.

Seemingly remote today, Iona was, in Columba’s time, at the centre of a maritime ‘highway’ linking communities along the length of western Scotland and northern Ireland. It was a place of great influence and played a crucial role in the conversion of the Picts and Northumbrians to Christianity. In Gaelic the island’s name is Eilean Ì (the island of Ì) or Ì Chaluim Chille (Columba’s Ì), giving Icolmkill, by which name it was known for centuries in English. The modern English name Iona derives from a mistranscription of the Latin form Ioua (Insula). The video clip below illustrates the important geographical position of the Western Isles.

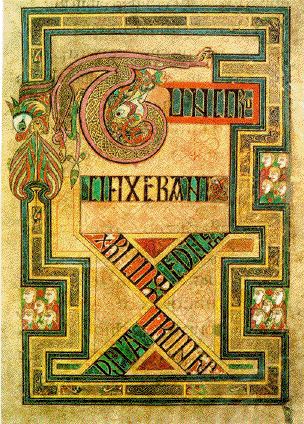

It is thought that the world-famous Book of Kells (now in Trinity College, Dublin) was started, and perhaps even completed, in Iona during the 8th century AD, before being removed to Ireland for safekeeping during the times of the Viking raids on the Hebrides in the late 8th century. Click here [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] for more information on the Book of Kells.

There is no significant evidence for Scottish military conquest of the Picts, or that the Picts were driven out physically. Around 841 Kenneth (Cinaed) mac Alpín became King of Dál Riata and, two years later, he unified the Picts and Scots under his leadership. As the language of status and government, Gaelic became nationally dominant, absorbing Pictish. The kingdom was called Alba (and still is in Gaelic), an ancient term related to Albion which, in the days before the Anglo-Saxon invasions, had referred to the whole of Britain.

Records of the country being called Scotland by English-speakers date from the 11th century; by this stage it is thought that Gaelic was the dominant language of the country, in both status and number of speakers.

The earliest records we have of written Gaelic are on stone in a script known as Ogham. But by the 6th century AD, monks in monastical scriptoria were starting to explore the use of the alphabet of the Church language – Latin – to write their own Gaelic vernacular. English and Gaelic have thus shared a similar alphabet for a very long time but, of course, the Latin letters had to be adapted to portray sounds which were not necessarily of identical quality in each language.

Anglophone readers soon learn that the English ‘rules’ which relate particular letters and letter combinations to particular sounds (and which are notoriously irregular in English) do not apply in Gaelic. The Gaelic language has its own rules. For example, a ‘b’ in the middle of a word is more like an English ‘p’. And a Gaelic peculiarity, not generally found in English, is the Svarabhakti (or ‘helping’) vowel (the term comes from ancient Sanskrit). This is a vowel sound which is not written but generally repeats (approximately) the preceding vowel. Alba, for example, is pronounced approximately ‘Al-uh-puh’.

Click on the sound file to hear its correct pronunciation

Gaelic slowly replaced Cumbric in most of southern Scotland, including the old kingdom of Strathclyde, in late medieval times. It is thought that, following the Scottish victory over the Northumbrians at the Battle of Carham3 (in the Borders) in 1018, Gaelic stemmed an Anglian advance in the south-east.

But it is unlikely that Gaelic, while being spoken by some of the ruling classes in Lothian and the south-east as far south as the border with England (and perhaps even across it), was ever numerically dominant in that part of the country. In 1091, when a Gaelic-speaking king ruled the lands north of the Tweed, except the far north and west which was under Norse control, the Anglo-Saxon chronicle records that Malcolm III (1058-93) went with his army ‘ut of Scotlande into Lodene on Englaland’ (out of Scotland into Lothian in England), presumably meaning that the dominant speech in Lothian was Anglian, or Inglis.

Malcolm III’s rule coincided with the challenge to Gaelic’s place at the pinnacle of Scottish power, and the start of its decline in southern and eastern Scotland can be dated from around the late 11th century.

Malcolm Canmore was a polyglot Gaelic king (his nickname derived from the Gaelic Ceann Mòr, ‘big head’, either in reference to a physical feature or to his kingship). He took the throne following the slaying of MacBeth at the Battle of Lumphanan in 1057. He married Margaret, a half-English princess whose brother’s claim to the throne of England was thwarted by the Norman invasion of 1066. Margaret, later canonised, promoted the cause of the English language in court and church.

Successive monarchs established and supported royal burghs in Gaelic Scotland, in which the ruling classes, often of Norman or Flemish ancestry, spoke English and were loyal to the crown.

Anglo-Norman magnates were granted land in various localities. While their preferred languages might originally have been Norman French and Latin, they became largely anglicised. The exceptions are some noted Highland clans of Norman origin4 – such as the Frasers, Grants and Chisholms – which became fully Gaelicised. At this stage it was only in the south and along the east coast that Gaelic was losing sway and, while the royal court, now firmly established in Edinburgh, might have spoken English, Norman French and Latin, the majority tongue of the ordinary people in Scotland as a whole was still Gaelic. It probably didn’t lose that status until the 15th century5.

However, the monarchs didn’t entirely divorce themselves from Gaelic tradition, Alexander III, for example, being crowned at Scone in 1249 in the traditional Gaelic manner. Robert Bruce, King of the Scots from 1306 until 1329, and victor at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, was of mixed parentage and almost certainly spoke Gaelic, among other languages; his father was of Norman extraction while his mother was from Carrick (now southern Ayrshire), then a Gaelic stronghold.

The Declaration of Arbroath, an appeal (written in Latin) to the Pope in 1320 for official recognition of Scotland’s status as an independent nation, makes it clear that the country’s nobles saw themselves as Scots, not Britons, Picts, Norwegians, Danes or English. The national identity had been forged, to a very large degree, by the Gaels.

While Gaelic was losing ground in the south and east, the opposite process was taking place in the north and west, with many people of Norse or mixed Norse-Gaelic ancestry being assimilated into Gaelic society. Perhaps the most famous is Somerled, who first appears in 1140 as the regulus or king of Kintyre. When both David I of Scotland and Olaf, King of Man, died in 1153, Somerled moved to extend his control over the Hebrides, eventually achieving mastery of a sea kingdom stretching from Man to Lewis, thumbing his nose in the process at the Norwegians who had long claimed sovereignty over the isles. Innse Gall, ‘The Isles of the Foreigners’, were once more becoming Scottish, and the dynasty created by Somerled was to become The Lords of the Isles, a Gaelic-speaking polity that grew to challenge the power of the kings of Scotland in the west and which finally succumbed only in the late 15th century. Watch the video clip below to find out more about the Lordship of the Isles. The video stresses the strength of this Gaelic-speaking sub-kingdom.

Norway ceded sovereignty over its territories in Scotland, with the exception of Orkney and Shetland, to the Scottish crown in the Treaty of Perth (1266), strengthening the hand of Gaelic throughout the west and north, and ensuring a full regaelicisation6 of the Hebrides. Norn, the local descendant of Norse, clung on for some time in Caithness, gradually being replaced by Scots in the north-eastern half of the area and by Gaelic in its south-western half.

By the late 14th century the anglicisation of southern and eastern Scotland had reached such an extent that the term ‘Highlander’ (or Hielandman) had become synonymous with ‘Gaelic-speaker’. To the Gael, the Highlands became the Gàidhealtachd (the land of the Gael) and the Lowlands the Galltachd (land of the non-Gael), although the Gaelic folk-memory has always appreciated the historical links the language had with Lowland Scotland. Click below to listen to the pronunciation of Gàidhealtachd and Galltachd.

By this stage, many English-speakers viewed the Gaels with hostility and considered them culturally and socially inferior. But as one English-speaker writing in the 1380s, John of Fordun, makes clear, Gaelic was still viewed, even in his community, as ‘the Scottish speech’.

‘[T]wo languages are spoken among them, the Scottish and the Teutonic; the latter of which is the language of those who occupy the seaboard and plains, while the race of Scottish speech inhabits the Highlands and out-lying islands. The people of the coast are of domestic and civilised habits, trusty, patient and urbane, decent in their attire, affable and peaceful, devout in Divine worship … the Highlanders and people of the islands, on the other hand, are a savage and untamed nation, rude and independent, given to rapine, ease-loving, of a docile and warm disposition, comely in person, but unsightly in dress, hostile to the English-speaking people and language … and exceedingly cruel.’