7 The school library

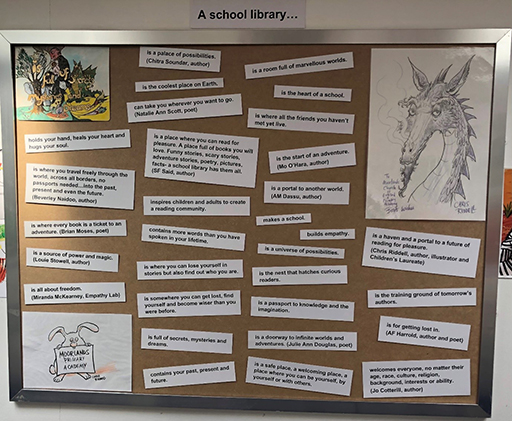

School libraries make a rich contribution to Reading for Pleasure. They offer access to a range of books and resources and provide another learning environment, as well as a safe space to read and talk about texts.

Libraries and librarians support and help create reading cultures by curating the book selection for readers, making books visible, offering programmes to excite readers and creating enticing spaces for reading (Loh et al., 2017). Consistently, international research, both large scale and case study, has demonstrated the benefits of school libraries (Teravainen and Clark, 2017; Gildersleeves, 2012; Williams, Wavell and Morrison, 2013). In particular these indicate:

- a strong relationship between reading attainment and school library use

- libraries are motivators of independent choice-led reading

- libraries foster personal development and positive attitudes to learning.

In the UK there is no statutory requirement for primary schools to have libraries, and there are few full-time trained librarians. Many schools devolve the work to reading leaders, teaching assistants and parent helpers, who can sometimes open the library before or after school or on Saturday mornings. Some schools also involve children as reading ambassadors. Rudkin and Wood (2019) found that enabling young people to help curate their library collections can have a positive effect on their engagement with library services and Reading for Pleasure.

Activity 5 Let’s love the library

Read Karen’s Robertson’s case study Let’s Love the Library [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . As you read, make notes on the strategies Karen used to involve children.

Comment

Seeking to ensure that the school library was shaped and ‘owned’ by the children, Karen listened to their ideas when offered through the suggestion box. Strategically, she involved the children in categorising the books in ways that suited them and also bought in more fiction as requested.

By timetabling library use and creating a comfortable atmosphere in which staff and children could browse, select, read, and chat about books, Karen succeeded in creating a buzz about reading in the library and beyond. Which strategy could you reshape for use in your context?

Now listen to the advice of Marilyn Brocklehurst, a children’s librarian who runs the Norfolk Children’s Book Centre. She offers tips on reviewing and developing school libraries, which will be applicable to your own classroom collection. As the English government’s Reading Framework (DfE, 2021) highlights, such areas need to be regularly refreshed and replenished and dull, dog-eared books removed.

Transcript: Video 2

Where local library services exist, schools can work to make maximum use of them, as they offer a wide range of books that can entice young readers and not just boxed sets related to subjects or topics across the curriculum. Linking to the local school library service or public library and helping children become members enables them to access a wider range of texts that may tempt and inspire them.

Despite the overwhelming benefits, disparities in library provision exist. In the UK, the Great School Libraries Campaign revealed that schools serving the most disadvantaged communities are almost five times less likely to have a designated library area than schools serving the least disadvantaged communities (44% vs 9%) (GSLC, 2019). School budgets are not as commonly augmented in areas of high economic challenge and furthermore, a recent National Literacy Trust libraries survey revealed that over a quarter (26.9%) of respondents expressed a need for more diversity within their current book stock (Todd, 2021).Without an inclusive book collection all children cannot see themselves in books. Looking internationally, concerns about the state of school libraries and the demise of public libraries in some countries significantly constrain efforts to develop the habit of Reading for Pleasure in childhood. At the time of writing, the challenges created by Covid-19, with library closures and concerns about transferring the virus, has exacerbated the difficulty some schools face in offering a range of high-quality texts in an enticing school library.

Another challenge is that some digital library systems, which have becoming increasingly popular recently, tend to position reading as a competition, an extrinsic motivator (Kucirkova and Cremin, 2017). Viewing reading in this way does not sustain readers in the longer term, as they read to compete, to gain points and rewards, not for the sake of the pleasure involved. As discussed in Session 2, considerable research evidence suggests that intrinsic motivation is more closely linked to developing a love of reading than extrinsic motivation (Orkin et al., 2018). However, digital library systems still hold value, not least because the use and accessibility of e-books can enlarge library stock and enable children to swap books, thus supporting a reading culture and widening children’s repertoires of known authors.

Children’s authors and illustrators can also play a valuable role in encouraging readers, as the next section examines.