2.6 Weather forecasting

It’s no secret that weather forecasting can be less reliable than we would like – particularly when looking beyond a week ahead. Although this field has seen huge improvements in recent decades, through advances in computing and the use of satellites, there are still limits to what can be achieved. Why is this? The answer lies in the data. Specifically, the quantity of data.

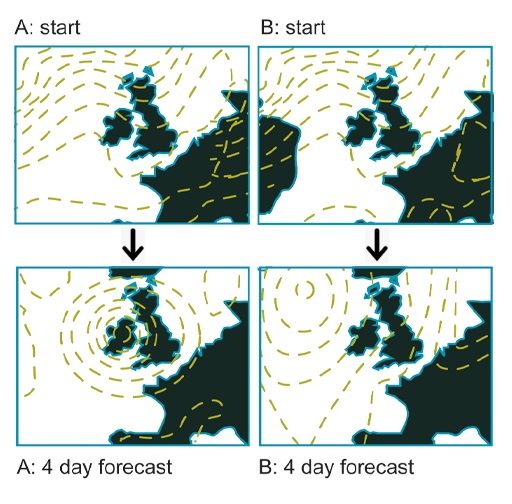

In order to make a forecast, we need to know the weather conditions now. Many thousands of observations are recorded around the clock in weather stations worldwide. These data are fed into high-speed computers as the initial conditions for a complex set of equations which model the weather and provide predictions of the weather as time evolves. The problem here though, is that a tiny change in any data – and there’s a huge amount of data involved – can lead to a very large change in the output after a relatively short space of time. This means that the model can work well in the short term, but runs into serious difficulties as more time passes. Furthermore, like with the equations resulting from Newton’s laws, the computer programs make tiny errors with each step of the calculation. As a result, even if perfectly accurate data for today’s weather were available, it would not be possible to predict its long-term changes with accuracy.

You’ve probably heard of ‘the butterfly effect’. This is a popular metaphor for sensitive dependence on initial conditions, which actually originated in the context of weather forecasting: it was the title of a talk given by the American mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz. The idea is that a butterfly flapping its wings over the Amazon might set off a tornado in Texas several weeks later. It is not the single act of the butterfly flapping its wings that causes the tornado, but that it might set in chain a sequence of events which eventually ends up with a tornado. The point is that in a complex system, it is almost impossible to know what results a small event might ultimately cause.