Picturing the family

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 March 2026, 9:04 AM

Picturing the family

Introduction

Most of us today take photographs for our family albums. The lucky ones among us have also inherited family photographs from the past. These photographs provide another type of record that can offer insights into our family history. But what can they tell us? How can we elicit the information they hold? And how do we analyse or evaluate that information? The purpose of this course is to suggest how to approach the interpretation of the photographic record.

Please keep referring to your own family photographs as you work through the course. This will help you assimilate the information and assist in the analysis of your own photographs.

Don't assume that once you have studied a photograph, you will have garnered all the information there is to be found. I am constantly surprised at how much I fail to see when I look at photographs. I have given talks using the same images to different audiences. Frequently somebody seeing an image for the first time will point out details I had not previously registered.

In addition, of course, an insight you discover about an image in your collection may have repercussions for others. So the process is one of continuous reading and reappraisal. Bits of the jigsaw gradually fall into place.

This course looks at some of the ways photographs can reveal, and sometimes conceal, important information about the past. It will teach the skills and provides some of the knowledge needed to interpret such pictorial sources.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 1 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand that photographs are shaped by a set of conventions based on ideas and practices which are not immediately apparent

understand that photographs, like other documentary records, are partial and biased

understand that photographs, like other documentary records, require critical analysis and careful interpretation

understand the importance of contextualisation in analysing photographs.

1 How to avoid damage when handling photographs

Remember to treat your photographs with the consideration demanded by their age and fragility. Careless handling and storage will cause damage.

- Handle photographs at the edges: the skin carries chemicals which cause deterioration (professional archivists wear cotton gloves).

- Hold a photograph in both hands or support an unmounted print with a piece of cardboard to avoid unnecessary handling.

- Never write on a photograph with anything other than a soft lead pencil (2B or 3B recommended). It is good practice to write a unique identity number on the back of a print and then make notes separately on paper.

- Never do anything to a photograph that cannot be undone without causing damage. Store photographs in a dark, dry, cool place.

The Bibliography section at the end of this free course contains books that provide more detailed information on the handling, storage and conservation of photographs.

2 Background history

2.1 Styles of photograph

Let's briefly examine the various styles of photograph that are commonly found in family albums.

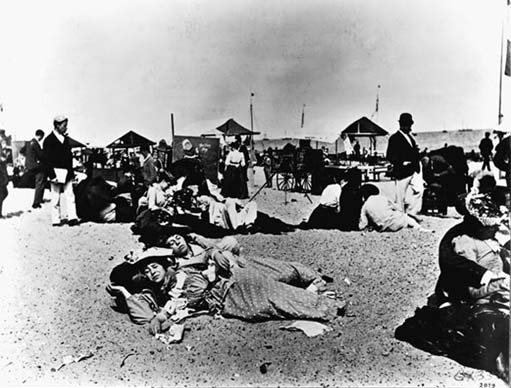

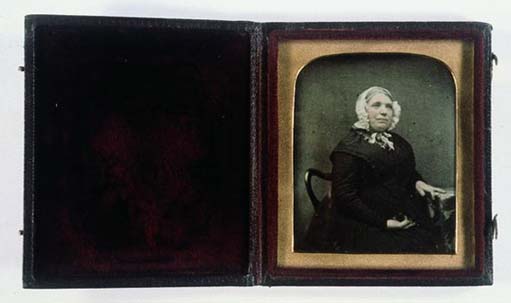

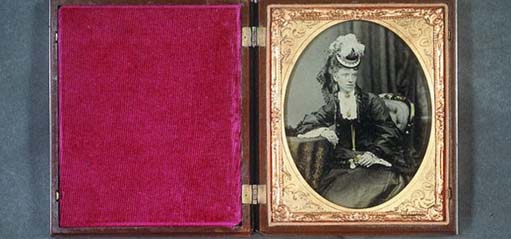

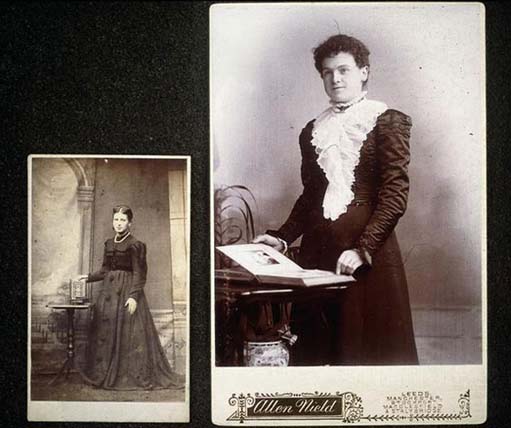

Figure 1 A photograph of a woman

Figure 2 A photograph of a woman

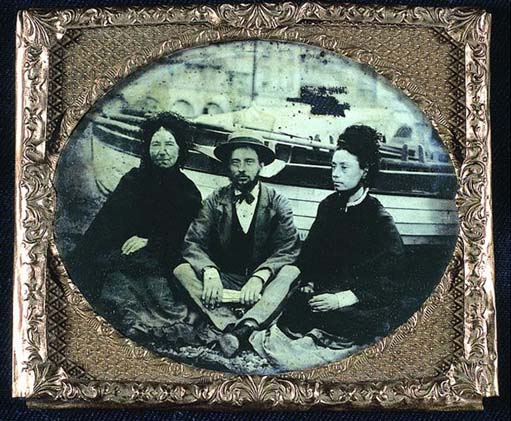

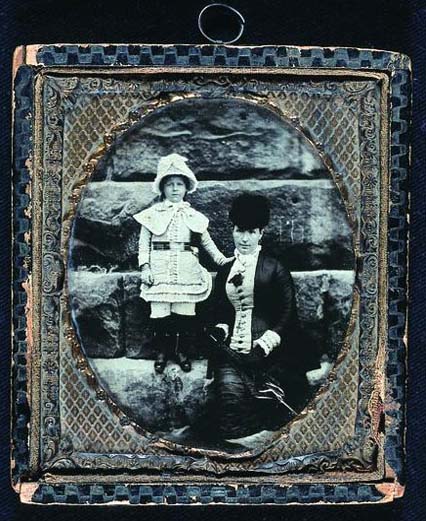

Practical photography was invented in 1839. The first photographic portrait studio opened in Britain in 1841. During the first 20 years photographic portraits were bought as one-offs in the shape of the daguerreotype in the 1840s and the wet collodion positive in the 1850s. Both formats came cased or framed and were designed to be carried on the person or displayed in the home.

2.1.1 Card mounted photographs 1860–c.1914

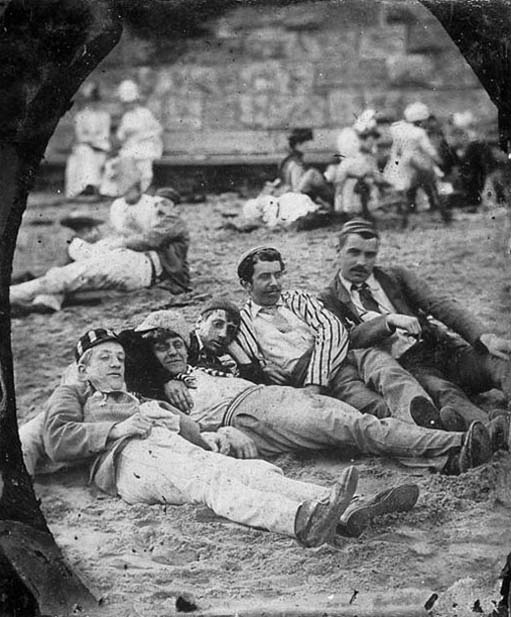

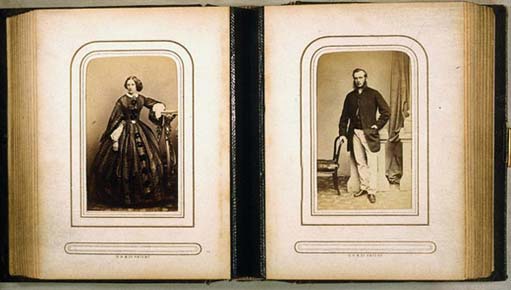

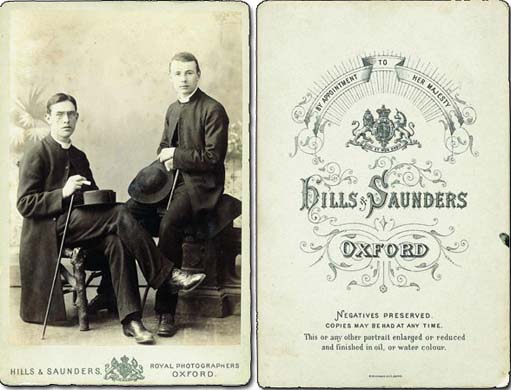

Figure 3 A photograph of two people

Figure 4 A photograph of two people

In Britain, standardization and mass production in photography came with the introduction of the carte de visite from c.1860. A larger version known as the cabinet appeared in 1866. Cartes and cabinets were paper prints of a standard size mounted on cardboard mounts of a standard size. They retailed by the score, dozen or half dozen and were housed in purpose-designed albums that appeared on the market at the same time.

2.1.2 Postcards c. 1902–1950s

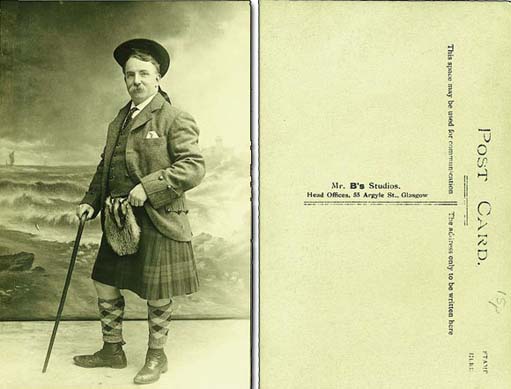

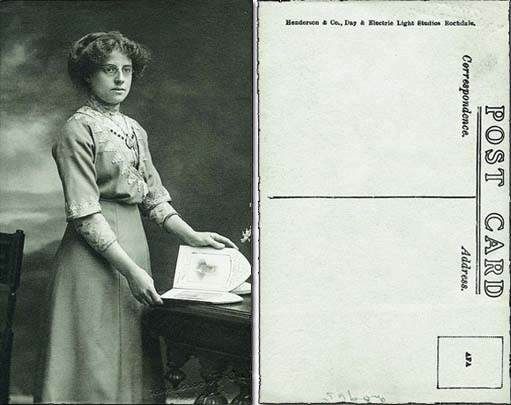

Figure 5 A postcard featuring a photograph of a man in a kilt

Figure 6 A postcard featuring a photograph of a woman

Although postcards were used for pictorial views in the late 19th century, the postcard format was not used for portraits until c.1902. It remained popular until the 1950s.

2.1.3 Amateur snapshots 1880s–

Figure 7 A photograph of a baby in a pushchair

Figure 8 A photograph of Arthur at his garden gate

Before the First World War, most family photographs were taken by professional photographers. In the 1880s, however, amateurs began to buy ready-made negatives over the counter and either undertook their own developing and printing or farmed this work out to commercial concerns. The amateur market expanded steadily, encouraged and sustained by commercial companies such as Kodak. By the second half of the 20th century most family photographs were taken by amateurs.

Photographs in the family album can therefore be divided into 2 distinct categories:

- portraits commissioned by the family and taken by commercial photographers for a fee

- snapshots taken by amateurs, usually family members or friends.

This course concentrates on the period when the professional was dominant, for the following reasons:

- Studio portraits are too readily dismissed as uninformative simply because people lack the necessary visual analysis skills.

- Studio portraits were produced to a formula which offers a congenial paradigm for developing skills of visual analysis and interpretation.

- These skills can readily be transferred to the later tradition of snapshot photography.

- Equipped with a knowledge of the practices of early professionals, we can make comparisons between then and now. This enables us to identify areas of continuity and change. We can then assess how far the 19th-century studio tradition continues to influence the snapshots we take today. We shall return to this question throughout the course.

But before we start to analyse the studio tradition in detail, let's consider the nature of the photograph as a source of evidence in historical research.

2.2 Photographs as primary sources

As a primary source of historical evidence the still photograph remains largely unexamined and unexplored. Many academic historians remain wedded to the written word and are often mistrustful or dismissive of the still image. Photographs continue to be used merely to prettify or to provide necessary breathing space in dense texts. In fact, the task of finding ‘illustrations’ is often only considered after a book is written. What could indicate more clearly that the photograph has never gained legitimacy as a historical record that can inform and mould authorial thinking and argument?

Photographs require as much scrutiny and critical analysis as written records. It is easy to think of them as ‘truthful’ and ‘objective’ because they are produced by a machine that reacts to light falling on the actual scene or subject. However, all photographs are created by human agency and photographers legitimately seek to influence viewers’ perceptions. A photograph does not present the subject ‘as it was’, but as the photographer wanted the viewer to see it.

Since 1839 various distinctive applications have evolved – portraiture, art photography, reportage, fashion, documentary and so on. Photographers working within these disciplines shared a common set of ideas about the nature and purpose of their work. They adopted practical procedures that enabled them to express these ideas in their photographs. Ideology and methodology worked together to shape the typical, generic image. We can learn about these ideas and practices from contemporary publications that offered advice to photographers.

Of course, there was cross-fertilization between the various applications and of course ideas and practices developed over time. But to explore the meaning conveyed by an image to its contemporary audience, we must try to understand the ideas and practices that shaped it. Our subject is domestic photography and the family album and these obviously belong to the portrait tradition. So in this course we shall identify the ideas underpinning the portrait tradition and investigate how these ideas translated into working practice.

2.3 Photographs as artefacts

Bear in mind that photographs are artefacts. This means that they are more than just images. The photographer, the process and the packaging all add something to our understanding of the role of the photograph. So, for example, the mount can indicate its purpose (exhibition wall, domestic display, album and so on) and the significance attached to the article in its time. The physical properties of a mount, such as the quality of the card or style of printing, can distinguish top-of-the-range products from the functional. These and other qualities such as thickness, texture, colour, style of decoration and any written information, printed or manuscript (i.e. hand-written), can assist in dating. I shall refer to the artefactual nature of the photographic record at various points in the course.

2.4 National variation

Relatively little research has been undertaken by photohistorians in the field of domestic photography. However, we should be aware that photography developed in different ways in different countries. So, for example, in Britain the daguerreotype remained a luxury article, as high prices restricted sales to the comfortable classes, whereas in America, because of early mass production techniques, studios could offer 4 daguerreotypes for 1 dollar.

Photography was, however, a European invention. Western practitioners exported not only the technology but also European traditions of portraiture.

3 The portrait tradition: ideology

3.1 Introducing ideology in portraiture

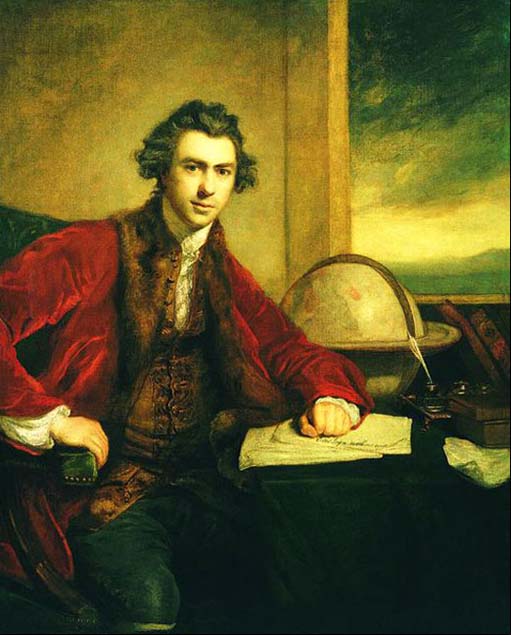

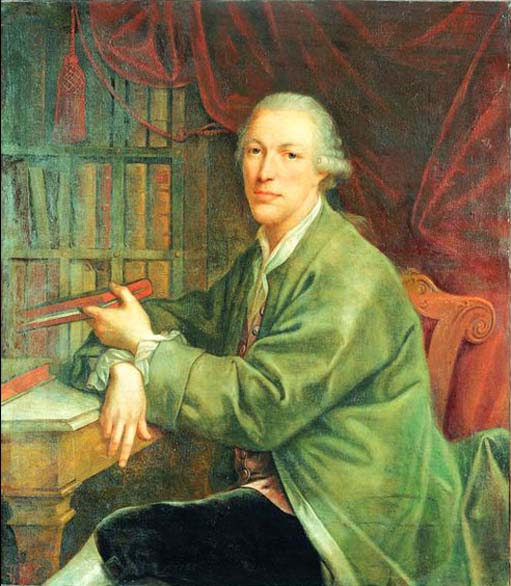

Figure 9 A painting of a nobleman seated at a desk

Portraiture emerged as the first major commercial application of photography because the camera could mechanize an established and profitable market in hand-crafted likenesses. By the early 19th century, most sectors of society had acquired the habit of buying portraits. Working people purchased penny profiles or silhouettes cut from black paper, the comfortable classes acquired miniatures of watercolours on ivory, and the rich commissioned their portraits in oils. Portrait photography retained this leading position until the end of the century.

The tradition of hand-painted portraiture in Europe dates back at least as far as the Renaissance. By 1839 painters had evolved a sophisticated professional rhetoric about the role of the portrait and the nature of the artist's interaction with the sitter. Clients, too, had expectations and attitudes based on existing practice. In mechanizing the likeness trade, early photographers were confronted with a ready-made set of ideas about the portrait and its purpose. Let's explore how photography responded to these ideas.

3.2 Idealisation

There were fundamental principles of painted portraiture that affected every element of the portrait, from expression and pose to background and lighting. The first imperative was the need to idealize the sitter.

Activity 1

Click on 'View document' below to open and read part of Audrey Linkman's article on 'Photography and art theory', then answer the questions.

Activity 1a

How did portrait painters acquire an appreciation of ideal beauty?

Answer

Painters studied nature but also placed considerable emphasis on making drawings of Greek and Roman statues. This discipline was known as ‘drawing from the Antique’. It gave painters a familiarity with the shapes and proportions used in classical sculpture that were greatly admired and respected by later artists.

Activity 1b

How did they resolve the dilemma between representing ideal beauty and accurate likeness?

Answer

Equipped with this knowledge of approved proportion and form, painters were expected to subtly modify those features of the real-life sitter that were considered inferior to the classical model. Such modifications were of course easier to make for the painter than the photographer.

Activity 1c

How did photographers respond to this notion of ideal beauty?

Answer

The new technology had the ability to reproduce appearance in accurate detail. In spite of that, photographers felt obliged to create a portrait which shadowed, concealed or excluded those physical attributes in the sitter which were regarded as defects, and to highlight features perceived as attractive according to the tastes of the time.

3.3 Limited positive characterization

The painted portrait was, however, perceived to be more than a mere ‘map of the face’. It was also meant to reveal aspects of the inner as well as the outer being.

Activity 2

Click on 'View document' below to open and read the remainder of Audrey Linkman's article on 'Photography and art theory', then answer the questions.

Activity 2a

What was regarded as the most important element of the portrait?

Answer

The portrait was perceived as more than a mere map of physical features. Its purpose was to reveal the inner soul and true character of the sitter. This added a moral and spiritual dimension to the portrait. It also conferred prestige and status on a profession that could claim the ability to fathom the inner recesses of the mind and reproduce character on canvas.

Activity 2b

How did the theory of idealization affect this important element?

Answer

Only positive qualities that reflected credit upon the sitter could be portrayed in the painting. The depiction of base qualities would conflict with the need to idealize the sitter. Consequently any attempt to portray character would be limited to the depiction of virtuous qualities. (I shall subsequently refer to this practice as ‘limited positive characterization’.)

In addition, it was thought that the viewer would be corrupted by the depiction of faults and vices in a painting. By looking at virtue in others the viewer might be inspired to moral improvement. In the early 19th century few people questioned the belief that the purpose of art was to inspire and ennoble.

3.4 Characterisation and sexual stereotyping

In attempting to characterise their sitters, 19th-century commercial photographers did not intend or attempt any serious psychoanalytical exploration of individual character such as we perceive it today in our post-Freudian world. They sought instead to stereotype by age and sex within a narrow range of positive virtues, which had previously been approved, within the conventions of painting: modesty, simplicity and chastity for women; dignity, strength and nobility for men.

3.4.1 Control of the sitter

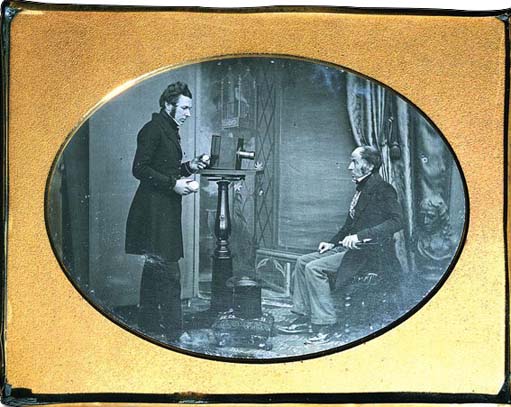

Figure 11 Jabez Hogg photographing W.S. Johnston

Photographers proved eager to model themselves on previous practice in another aspect of their approach to portraiture. The painter potentially enjoyed total control over the portrait: pose, background and expression were all determined by each application of the artist's brush. The painter, in effect, controlled the sitter. It therefore became important in terms of their own professional rhetoric that photographers, too, should be seen to exercise similar control over their subjects.

Virtually every 19th-century manual on photographic portraiture had a chapter on managing the sitter. The photographer's role was to direct; the sitter's only response was to acquiesce. Sitters who expressed ideas of their own became, by definition, ‘difficult’.

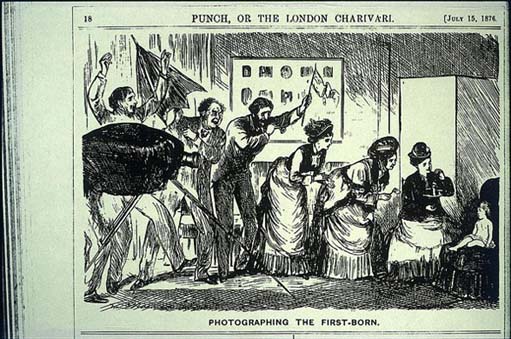

Figure 12 A cartoon of a newborn baby being photographed

Photographers were warned against allowing their own superior judgement to be influenced by the sitter.

In the studio all men are not equal; all men are inferior, for the time, to the artist: but unless he would awe, he must conceal this power by tact and affability.

(Anon, 1884, p.388)

Activity 3

Various stock types of difficult sitter recur in the literature. Painters, of course, posed the biggest threat. Other difficult customers included those accompanying sitters: the gentleman with the lady, the mother with the child, the owner with the pet.

Activity 3a

Why did painters pose the biggest threat?

Answer

Painters could challenge a photographer's authority because photography had usurped the rhetoric of painting. Painters could therefore challenge a photographer's artistic judgement because they were familiar with the arguments and the attendant practical difficulties. Painting was also perceived as a superior art form because painters worked from the imagination.

Activity 3b

What's the significance of the gentleman, the mother and the pet owner in this context?

Answer

These people were, in contexts outside the studio, normally seen to be in control of the sitter. They were, potentially, more likely to challenge the photographer's decisions in order to maintain their position of control within the studio.

Early photographers were concerned with achieving recognition for their ‘mechanically produced portraits’ and social status for their ‘profession’ by conforming as closely as possible to the existing rhetoric of painted portraiture. Photographers incorporated existing ideas about idealization, characterization and sexual stereotyping into their own professional rhetoric. They also attempted to represent themselves as able to exercise total control over the sitter in order to establish authorship of the photograph.

Let's now turn from the ideology of portrait photography to examine the practices employed by photographers to carry these ideas into effect. You'll look at the specific elements that constitute the portrait – facial expression, pose, background and lighting – and explore how notions of idealization and characterization influenced their treatment.

4 The portrait tradition: methodology

4.1 Facial expression

Facial expression was considered the most crucial element to success in painted portraiture. It was the vehicle through which intangible qualities of mind and soul were conveyed. In painting the idea was to achieve the ideal expression, a synthesis of character and the spiritual essence of being. Although cameras could portray any number of expressions with relative ease – an advantage of the machine over manual practice – early portrait photographers continued to believe in the ideal expression which could epitomize an individual's character and experience.

Dedicated photographers attempted some originality of expression in portraiture and art work intended for exhibition. Commercial photographers, however, adopted the convention of a formal, unsmiling expression. You may be familiar with the standard explanations for the absence of smiles and laughter in Victorian portraiture, namely long exposure times, which meant that sitters could not hold a smile, or the theory about concealing bad teeth. Let's see if these explanations hold water.

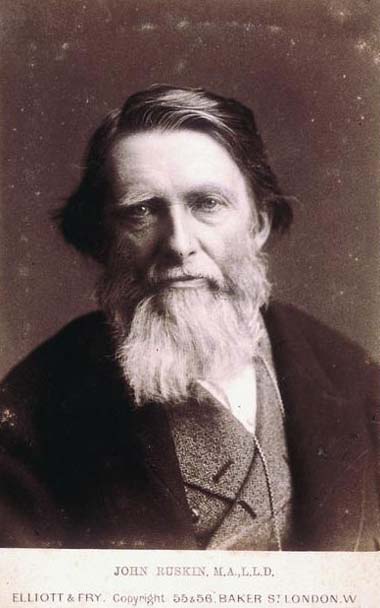

Activity 4

Look carefully at Image 13, a portrait of the artist, writer and critic John Ruskin. What qualities do you read into his facial expression? It may be helpful here to compare Ruskin with the smiling expressions (‘Say cheese!’) we adopt in front of the camera today. Note down your ideas; we shall return to them later.

Cartes de visite and cabinet portraits of celebrities – royalty, politicians, church ministers, actors and writers, for example – retailed in print shops, fancy goods outlets, stationers’ and photographers’ studios in the 19th century. They were placed in family albums alongside the portraits of relatives. Many of these celebrity portraits carried no identification of the sitter. From 1862, manufacturers could attempt to protect their rights in the work by registering the image at Stationers’ Hall. The word ‘Copyright’ on the mount can indicate that the image was so registered though this is not always the case. Photographers paid a fee and filled in a form which usually (though not always) carried a copy of the image. These copyright records are held today in the Public Record Office at Kew. This splendid resource is unfortunately difficult to access as it is organized only by date of registration.

Activity 5

Click on 'View document' below to open and read 'The anatomy of expression in painting' by Charles Bell, 'The photograph and artistic colouring' by Alfred H. Wall and 'The studio and what to do in it' by H. P. Robinson. These are extracts from 19th-century manuals and articles giving artists and photographers advice on expression in portraiture. Answer the question below.

What qualities did laughter and smiling convey to artists and photographers in the 19th century?

Answer

Bell (Item 31) is very clear about the expression he regards as unacceptable. Broad laughter was vulgar and ludicrous. Smiles could convey various meanings. But the preferred expression, variously described as ‘a certain mobility of the features’ and ‘an evanescent illumination of the countenance’ was ‘more enchanting than the dimpled cheek’.

For Wall (Item 32), a smile, once fixed and permanent in a photograph, appeared as a ‘piece of affectation’ or ‘mere grin’. And grinning was objectionable.

Robinson, too (Item 33), regards broad laughter as intolerable when fixed in a photograph, though beautiful in life because of its transience. He quotes at some length the attitudes of the sculptor John Gibson. This is a way of giving his own preferences added authority. Gibson regards smiles as frivolous and favours a serious and calm expression as it represents ‘men thinking, and women tranquil’. Gibson's distinction between the sexes reveals evidence of sexual stereotyping. This is extended in Robinson's approval of a ‘cheerful’ expression for ladies and a happy expression for children. The notable absence of any reference to men in this context suggests that the Victorians regarded smiles as frivolous and lightweight.

Activity 6

Now return to your notes from Activity 4 and compare your ideas of the qualities you read into Ruskin's expression with the qualities that Victorians might have read into it.

Answer

Serious expressions convey to our generation the idea that a person is stern, miserable, morose or gloomy. In contrast we read into the smiles of our contemporaries notions of success, confidence, warmth of personality, friendliness and fun; in short, positive values. The Victorians would have approved of Ruskin's expression as concealing any public display of emotion. It appears calm, controlled and dignified, qualities indicative of a thoughtful mind, a man who took himself seriously and invited others to do likewise.

The interpretations placed on expression, then, are relative to culture and date. We have returned to the issue of context which was so vital to our reading of written records.

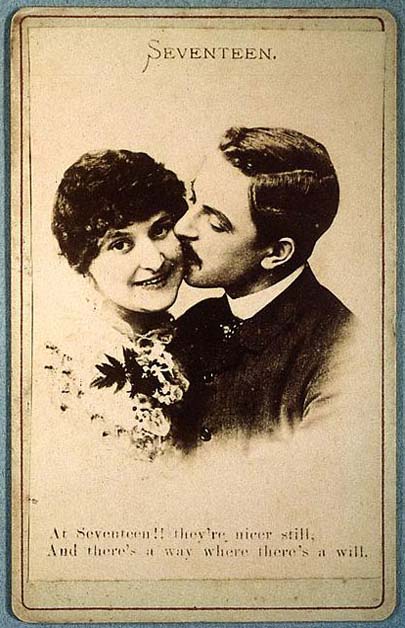

Figure 14 A postcard

Figure 15 A postcard

Smiles could certainly be achieved in Victorian portrait photography, but were normally restricted to commercial or humorous photographs for the retail trade. Actresses frequently smiled in their portraits but as their social status was equivocal, the smile in this context could be interpreted as availability or invitation. The ‘respectable’ distanced themselves from such connotations in their family portraits.

So I think we can reasonably argue that the absence of smiles in 19th-century portrait photography was not due to technical considerations. Indeed, when the gelatine dry plate succeeded the collodion wet plate negative in the 1880s, exposure times were reduced to fractions of a second yet we do not witness any immediate or widespread outburst of smiles and laughter in the family album.

4.2 Pose

Pose followed expression on the list of the portrait photographer's priorities. A sitter's pose was intended to assist idealization by highlighting physical beauty. Photographers were required to select a pose that displayed the sitter to advantage.

If your sitter be tall and thin, or short and stout, select a pose which may render such peculiarities least prominent …A sitter's personal defects may be frequently concealed by the choice of position.

‘Defects’ in this context included physical blemishes and disfigurement. Such imperfections could be bathed in shadow or excluded altogether by careful framing, vignetting or masking.

Activity 7

Please take a few minutes to study this delightful (I think) portrait of Walter J. Eastwood. Do you get the feeling that there is something about this picture that you can't quite put your finger on? Can you think what it might be?

Answer

Walter had a disability affecting his spine and you will notice that the photographer has selected a pose that hides his back from view. The photographer would certainly have regarded this attempt to conceal impairment as a proper professional approach. The fact that the photograph survived in the family album suggests that the customers, too, were happy with the result. The politics surrounding disability today would, however, lead us to question the desirability of this approach.

Photographers were encouraged to aim for an elegant, graceful and fluid pose. These qualities characterized the genteel and educated in Victorian society. Their emulation by the less privileged was intended to suggest refinement and so assist in the idealization of the sitter.

Activity 8

Look closely at Image 17, a photograph of two young clerics. Then answer the two questions below.

Figure 17 A postcard featuring two churchmen

Activity 8a

1. Compare the pose of the sitters with the poses that you and your friends might adopt in front of the camera today. Make a list describing 19th-century poses and another describing 21st-century behaviour.

Answer

I know from my experience of using this photograph in my teaching that many people today describe the body language of these men as stiff, formal and constrained. By comparison the poses we are happy to adopt in front of the camera appear (to us) more comfortable and relaxed. However, the relatives of the sitters in this example would no doubt have approved of the poses, regarding them as easy, elegant and entirely appropriate to the churchmen's superior social status. That was certainly the intention on the part of the photographer, and the pose conforms to the instructions in early manuals of good practice.

Activity 8b

2. If you have identified any differences between then and now, how should we interpret them? Think about our earlier exploration of the meaning of expressions and how these have changed over time.

Answer

As with facial expressions, we do need to question what messages we read into the relaxed body language of today. If you agree with me that it carries overtones of spontaneity, self-confidence and ease with the world, then we are continuing the conventions of our Victorian predecessors in projecting positive images of the sitter. Indeed, I would argue that the wider society has changed its attitudes and our snapshots reflect those changes, but that our snaps continue to fulfil the same role in presenting a positive view of the family.

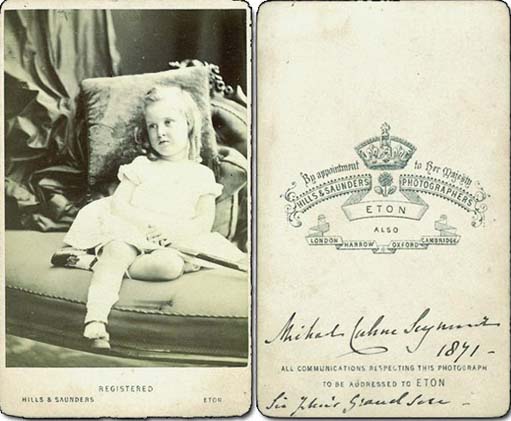

I have included the verso of this portrait to focus attention on the photographer. The firm of Hills and Saunders was established in Oxford in 1860 and it subsequently opened branches in Cambridge, Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Sandhurst and elsewhere. The siting of its various branches reflected the firm's single-minded pursuit of a specific client group – that of the public school boy destined for university and a career in the military, the church or other professions. The social status of the sitters can be deduced from the class of studio they patronized.

In many early portraits the subjects appear to be uncomfortable and constrained, I suspect because they were asked to assume positions which did not come naturally to them. The fact that their discomfort is communicated in the portrait reflects badly on the photographer!

4.3 Characterisation and sexual stereotyping

The choice of pose was also intended to echo the limited positive characterization of the expression. Distinctions were inevitably drawn between poses regarded as suitable for males and those considered appropriate for females. Men were allowed greater variety of poses than women.

The pose of a lady should not have that boldness of action which you would give a man, but be modest and retiring, the arms describing gentle curves, and the feet never far apart.

(Wall, 8 March 1861, p. 110)

For both men and women it was routine practice to find head and body set at slightly different angles. This prevented a wooden appearance by introducing a slight suggestion of movement into the composition. In portraiture in general it was normal for the gaze to follow the direction of the head.

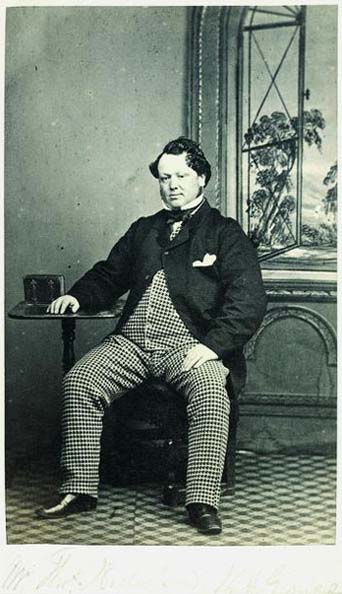

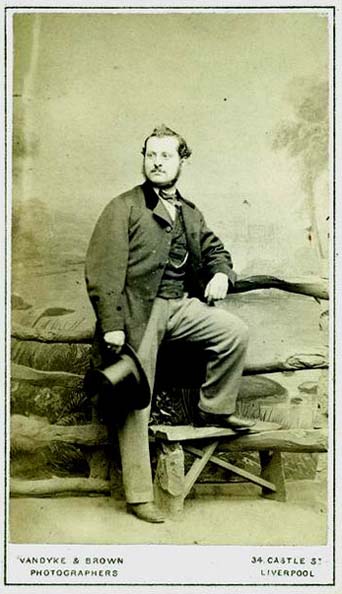

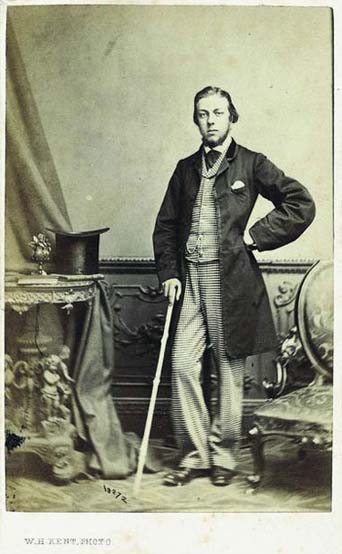

Activity 9

Spend at least 5 minutes comparing these portraits of men and women. Look in particular at the position of arms and legs, the set of the head and the direction of the eyes.

What differences in pose can you identify between the men and the women? Make a note of your findings. Do you think that these differences help to suggest different qualities? If so, what qualities can you identify?

Figure 18 A photograph of Thomas Nicholson

Figure 19 A photograph of an unknown male

Figure 20 A photograph of an unknown male

Figure 21 A photograph of an unknown female

Figure 22 A photograph of an unknown female

Figure 23 A photograph of an unknown female

Answer

The poses of the women are characterized by a relative lack of exertion or activity. The lack of movement can convey repose, calmness, quiescence or even passivity. The slight variation in the angle of head and body, allied with their inactive poses, adds grace. Whether standing or seated women normally keep their arms close to the body. This suggests self-containment and little interaction with the outside world.

It is less common (though certainly not unknown) to find women gazing directly at the viewer. The frontal gaze can project strength, courage and engagement. It can also be perceived as confrontational. Women usually have their gaze averted. If they are looking downwards, the pose can suggest meekness, modesty and docility. In general, however, gaze has to be interpreted in relation to other elements of the image.

In marked contrast with the women, the men can cross their legs, set them apart or stand with one foot higher than the other. These poses can suggest a sense of ease with the world, alertness, energy and activity. The different angle of head and body in males can sometimes be used to emphasize the suggestion of action conveyed by arms and legs. Men can convey notions of authority, assurance, assertiveness and engagement with the world by projecting arms, knees, elbows, walking sticks, umbrellas and top hats into the space around them.

4.4 Groups

If we agree that the posing of individuals carried messages for the viewer it makes sense that the posing of family groups can similarly be made to convey suggestions about the family and its character.

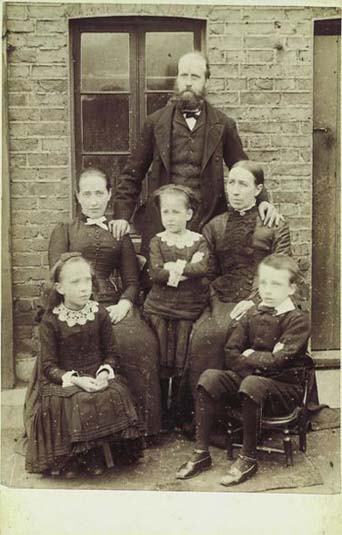

Activity 10

Scrutinize the arrangement of the sitters in the family group in Image 24. In such groupings it's important to consider the overall effect, the position and pose of each individual, the direction of heads and eyes and to note who is touching whom.

Figure 24 A photograph of an unknown family group

Activity 10a

Note down some words to describe the arrangement of the individuals.

Answer

This is a balanced composition with a woman and child strategically placed on each side and the man forming the apex of the triangle. The family is grouped closely together. In this way the photographer suggests underlying notions of closeness, harmony and unity – ideals which the family strives to achieve.

Activity 10b

Do you think the arrangement subtly influences your attitude to this family?

Answer

The man's position at the apex obviously embodies his pivotal role as head of household.

4.5 Touch

Let's consider more closely the nature of touch and physical contact normally displayed in Victorian studio portraits.

Activity 11

Compare Images 25 and 26, which are portraits of Edward, Prince of Wales and his fiancée Alexandra. Notice in particular the different poses. These pictures formed part of a series issued by the reputable Belgian firm Ghémar Frères on the couple's engagement in 1862. Image 26, in which Alexandra has both hands on Edward's shoulders, provoked critical comment in the British press.

Pretty, is it not? – sentimental, sweet, and lover-like? Very – only not quite probable, or in the best taste. That a young lady may have stood, in that attitude oftender watching, at the chair ofher future husband, is likely enough, – but she would never think of being photographed at so confiding a moment. The lover would certainly object to the artist ‘posing’ his intended in any such way, and the lady herself would object to it with still greater vehemence. Can Paterfamilias possibly believe that the Prince and Princess allowed themselves to be shown after this fashion to the general gaze?

What conclusions can be drawn from the critic's comments? Note down your thoughts.

Figure 25 A photograph of Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Denmark, on their engagement

A photograph of Edward, Prince of Wales and Alexandra, Princess of Denmark, on their engagement

Answer

The public display of emotion conveyed through touch or physical contact was clearly regarded by the critic as bad taste and objectionable. The critic considers the ‘attitude of tender watching’ and ‘confiding’ moment as an act of intimacy which should properly be veiled in privacy. The critic expresses particular concern about the indelicacy of permitting a photographer to pose a lady in this way. The critic also feels that fathers, as heads of household and arbiters of family morals and behaviour, could not be expected to approve of such images entering the public arena. Remember that we have met this reaction against the public display of emotion before, in relation to emotion in facial expression.

4.6 Touch and feeling

Activity 12

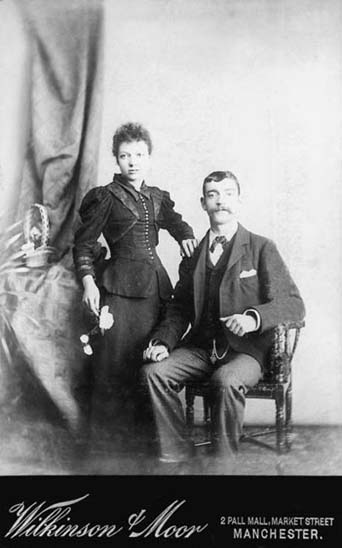

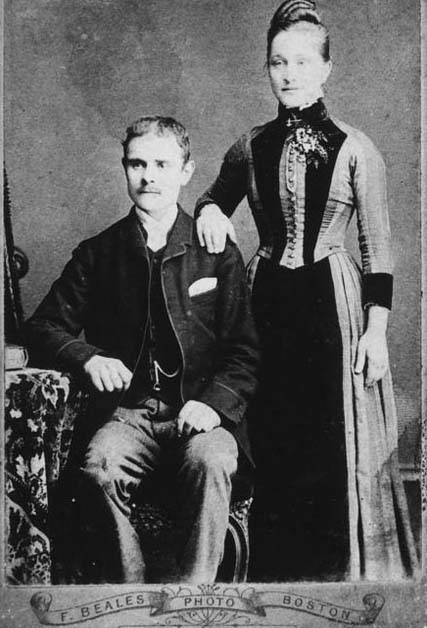

Images 27 and 28 represent the conventional pose of the newly-wedded couple who would visit the studio sometime after marriage to commemorate the event with a portrait. (We shall look at wedding portraits again later in the course.)

How would you characterize the nature of their physical contact? Jot down a few words to describe what you see.

Wedding photograph of William Henry Toyne Brocklesby and Susan Smalley

Answer

This is not the touch of desire or passion; no thrill of excitement passes between man and woman, no reciprocal spark of emotion – nor even indeed warmth or gentle affection. Instead, it is a touch that requires no response, cool, impersonal, apparently devoid of feeling. In conventional Victorian commercial portraiture, touch conveyed possession or close relationship. If touch conveys feeling then the portrait requires closer examination and explanation.

4.7 Exceptions

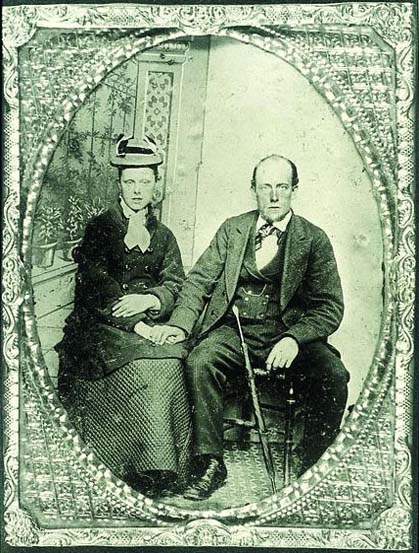

Activity 13

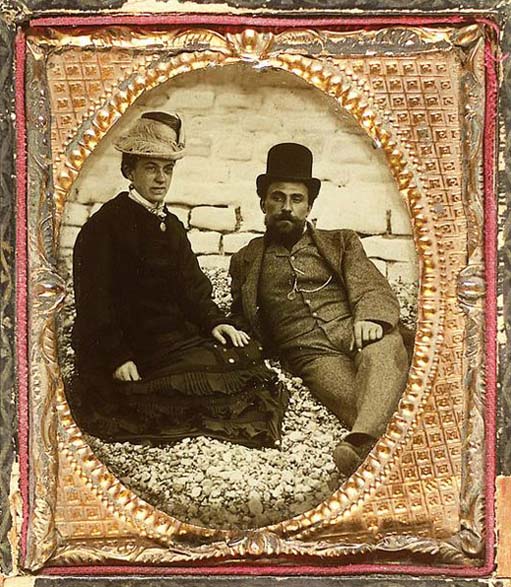

Do you think the contact between the people in Image 29 is different from that in Images 27 and 28? Can you describe the nature of the contact?

Answer

In this delightful example I would argue that touch actually does convey feeling. His fingers cover hers and both hands rest on her thigh (though quilted skirt, woollen jacket and excessive quantities of undergarment intervene between flesh and flesh). His firm clasp conveys a sense of earnestness on his part and consent on hers.

The flagrant breach of conventional practice in Image 29 has occurred precisely where Victorian photographers would expect to find it – in front of the camera of the itinerant photographer. (We shall look at the work of itinerants later in the course.) These speculative operators were held in contempt by proprietors of respectable high-street establishments. They were accused, amongst other things, of paying scant regard to posing by allowing each customer to ‘have his own way entirely’ as long as ‘he pays his sixpence in advance’.

I can find no evidence of a ring on the woman's hand, which suggests that the couple was not married. No respectable woman, however, would consent to be photographed with a man to whom she was not related unless she wished to publicize the message implicit within this photograph that both parties had reached an understanding and intended to marry. Such a photograph served a similar purpose for less privileged couples as the formal engagement portrait for the more affluent. Shown to family and friends it would signal their future intentions. Viewed in this way the dialogue with the viewer, as expressed by their poses, seems highly appropriate.

Mary was a cotton-weaver, and James worked as a plate-layer on the railways. They married in 1877 which gives a good approximate date for the photograph. In 1877 Mary was aged c.22 and James 27. After marriage they lived at Hawk Green, Marple in Cheshire. They had 8 children of whom 1 died in early childhood and 2 were killed in France in the First World War.

Careful analysis of the image enables us to identify standard treatment and to pinpoint distinctive or irregular features. If we can discriminate between the usual and the unusual, we can isolate elements which may help us acquire deeper understanding of the subject. In this way photographs can be mined as sources of information rather than undermined as mere illustration.

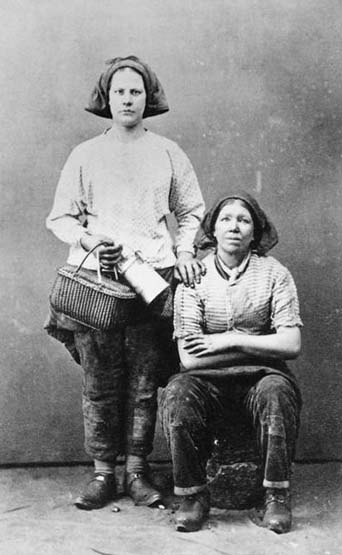

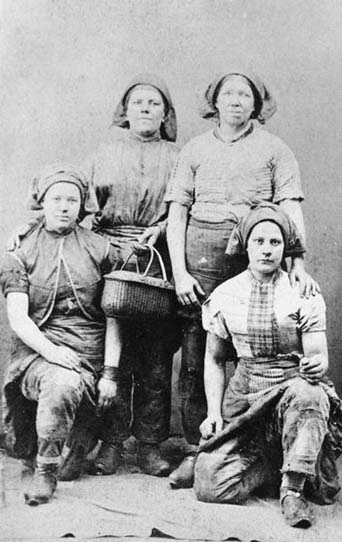

Images 30 and 31 are portraits of Wigan pit brow lasses. In the second half of the 19th century women were employed to work above ground at collieries in the Wigan area. They attracted public attention in the 1860s as a result of government enquiries into conditions in the coal mines.

A photograph of two pit brow lasses

A photograph of four pit brow lasses

Images like these were produced for the commercial market, just like the earlier portrait of John Ruskin (Image 13). They were taken by local photographers and sold to visitors as novelties. The lunch baskets and tea cans add interest. These portraits of local colour were the precursors of the picture postcard and similar images depict fishermen and women, milkmaids and so on. They should not be confused with privately commissioned portraits of people in working dress.

Activity 14

Pit brow lasses were distinctive and controversial in Victorian society because they wore trousers. Some even feared that this habit could lead to a loss of femininity and moral degeneration in the wearer. A number of 20th-century critics have described these pictures as titillating and exploitative – the soft porn of the Victorian era!

Can you now identify any evidence in Images 30 and 31 that could be used to support such an interpretation?

Answer

The women are photographed with their legs apart. (Do you remember the firm instruction when posing women – ‘the feet never far apart'?) These are the poses conventionally reserved for males. So at the very least the photographer is seeking to emphasize the notion of maleness conferred by the wearing of trousers. This alone must have created a little frisson of excitement for viewers accustomed to contour-concealing, floor-length skirts, though we should bear in mind that these images were sold openly over – and not under – the counter.

In addition I think it reasonable to argue that the poses of the seated woman in Image 30 and the one kneeling in Image 31 are even more suggestive. They lead the eye (and thoughts) to regions that have no exposure elsewhere in the Victorian family album. It is interesting to note that the issue of males and females sitting with their legs wide apart remains contentious today.

I am not quite sure about the significance of the hands on the shoulders. It certainly echoes the male/female pose of the newly-married couple. On the other hand members of the same family can touch each other in the same way. So perhaps here touch denotes comradeship.

Most (though not all) of the women appear to be looking straight at the viewer. As we have already noted, gaze needs to be interpreted in relation to other elements of the image, and in this context the frontal gaze could be regarded as adding a note of challenge and provocation.

4.8 Backgrounds and accessories

Purpose

By now you have sufficient familiarity with early portraits to know that photographers regularly used painted backdrops and accessories to create a sort of stage set within the studio. These backgrounds came into widespread use with the introduction of the carte de visite in c.1860. Until the Second World War, 2 scenarios remained popular: the interior setting with windows, curtains, table and chair; and the parkland setting with trees, balustrade, rustic bench or stile. This choice of backdrop provides the most visible evidence of photography's debt to portrait painting.

Activity 15

Study this (I think) lovely picture of Hiram and Lily Broadhurst with their sons George and Arthur, taken in 1911. It provides a good example of a painted interior backdrop which includes wainscoting, French windows and floor-length curtaining. We know that Hiram Broadhurst worked in the tram sheds in Denton near Manchester when this portrait was taken.

What purpose does the backdrop serve in the portrait? For example, do the painted backdrops have any connection with the theory of idealization?

A photograph of Hiram and Lily Broadhurst with their sons, George and Arthur

Answer

The backdrop confers anonymity by divorcing people from their actual settings and circumstances.

At the same time the backdrops hint at wealth and elegant lifestyles. For instance, wainscoting and French windows conjure up ideas of traditional, gracious rectories in the home counties; appointments which did not feature in the terraced houses of the industrial city. Indeed Hiram and Lily Broadhurst would have counted themselves very fortunate to rent a house with a bay window and an inside toilet!

So we can conclude that backdrops were indeed intended to play a part in the idealization process.

Idealisation

If we look at the surprisingly small range of items commonly used as accessories we notice that they, too, confer prestige by association or continue the limited positive characterization. Children are often pictured with prestigious, manufactured toys. Do you remember Walter Eastwood's classy tricycle in Image 16? Boys hold whips or hoops suggestive of street games and the outside world; girls clutch dolls or baskets of flowers which evoke the domestic realm.

The book probably appears more frequently than any other item. It is used to imply education at a time when many people were illiterate.

A photograph of a female

A photograph album (as in Image 33) frequently takes the place of the book. The purpose-designed album with apertures to display the photographs appeared on the market together with the carte de visite in the early 1860s. With its tooled leather covers, metal clasp and gilt edgings, the album was designed to imitate the appearance of the Victorian family bible.

Activity 16

Can you think why the photograph album should be designed to resemble the family bible?

Answer

The Victorians often recorded family births, marriages and deaths in the front of their bibles. One contemporary commentator predicted that the family album ‘will supersede the first leaf of the Family Bible’ and become ‘an illustrated book of genealogy’ (Anon, 1861, pp.341–2).

The imitation and evocation of bibles, hymnals and other books used in Christian worship suggests that photography was attempting to position itself as a force for good in society. In its early years, photography was promoted as a refining and improving influence within the family.

On a more worldly level, it placed albums in the luxury class of household possessions which would in turn help establish the status of photography as an honourable and respectable occupation.

4.8.3 Personal possessions

Most accessories in studio portraits were supplied by the studio. However, it was not uncommon for sitters to introduce items that held a special significance for them, such as children's toys, competition trophies and awards gained in the course of a career. As we should by now expect, any personal items were intended to reflect credit on the sitter.

If we can distinguish the routine studio accessory from the prized personal possession, we may be able to elicit a few more nuggets of information about the sitter.

Activity 17

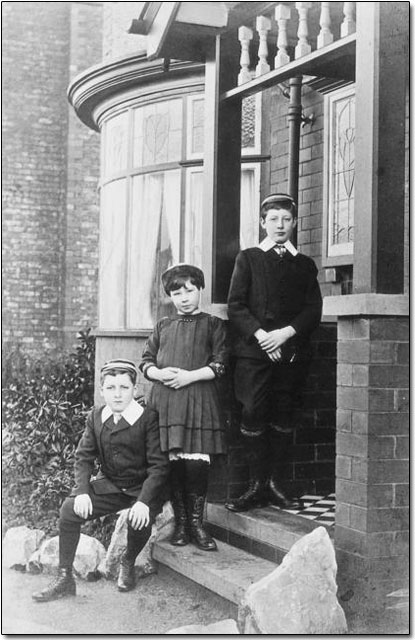

Can you identify anything in Image 34 that may be a personal possession rather than a studio accessory?

Answer

Though photographs were commonplace accessories, sitters did sometimes introduce their own photographs of loved ones who, for whatever reason, could not appear in the portrait in person. The girl on the left of this group is holding a portrait. Under a magnifying glass this appears to be an adult male.

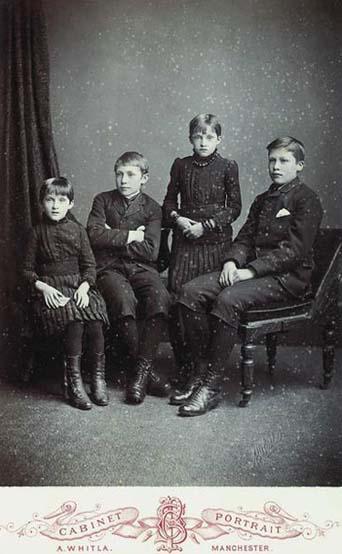

This portrait is curious because the children have no contact with each other but are likely to be brothers and sisters. The girls are wearing dresses of a similar style. This was normal practice for sisters in the Victorian period. The boys, too, are wearing similar outfits. Bands of material around the waist, cuffs and skirts of their dresses were made of crepe, the material that was traditionally worn during periods of mourning following a death in the family.

I know from other documented examples that orphaned children were sometimes photographed as a group before they were dispersed amongst relatives to continue their lives apart. It is not too far-fetched to surmise that the death of the father who is featured in the photograph has triggered a similar fate for these children. Their impending separation is foretold in their poses.

4.9 Lighting

4.9.1 Natural light

Activity 18

Can you identify the source of light used to create this portrait?

Answer

Natural daylight provided the major source of lighting for photographic studios throughout the 19th century.

Because of the need for unrestricted light, studios in towns were usually situated on the top floor of buildings. After an early period of experimentation the standard daylight studio had glass in a section of the roof and part of the way down the corresponding side wall. You can just see this arrangement in Image 35 which was pasted as a record of sales into the daybooks of the firm of Camille Silvy. Silvy's studio at 38 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater, served the elite of London society in the 1860s. Ideally light entered the studio from the north as this offered protection from the direct rays of the sun and so ensured a constant, uniform quality of illumination.

An illustration of a man taking a photograph of a woman

The light entering the studio could be controlled by using clear, stippled or ground glass and by fitting blinds, curtains and reflectors. Direct light gave sharpness, diffused light softness and they were used in conjunction. Reflected light gave detail to the shadowed side.

4.9.2 Idealisation

Early photographers were adept at using natural lighting to idealise the sitter. Manuals of good practice were full of advice on adapting the lighting to soften wrinkles and wreathe blemishes in shadow.

For ladies of a certain age, who often give the photographer a deal of trouble, it is advisable to employ a very soft light falling in front, which softens the wrinkles and protuberances of the face, and obliterates the disagreeable shadows formed by those parts.

A photograph of an unknown female

A photograph of an unknown female

Images 37 and 38 demonstrate how the appearance of the sitters could be affected by the use of lighting. The woman in Image 37 displays some lines and furrows, while the smooth face of the woman in Image 38 shows evidence of retouching on the shadowed side.

4.9.3 Limited characterisation

The other function of lighting was, inevitably, to assist characterization. Since Robinson advised portrait photographers to show sitters as moderately calm ladies and gentlemen, the lighting in commercial work is usually quiet and uniform, without dramatic contrasts of light and shade. This was intended to suggest tranquillity, harmony and self-control, in keeping with the limited stereotypical characterization discussed previously.

The use of lighting to convey dramatic characterization is more evident in Victorian art photography. Certain qualities were associated with particular effects.

Gladness abounds in the brilliancy of sunshine; placidity and peace speak most eloquently in the harmonious blending of subdued tones; and a general gloom, with intense black shadows, has a gaudy, powerful voice when associated with the rugged and the desolate.

4.10 Retouching

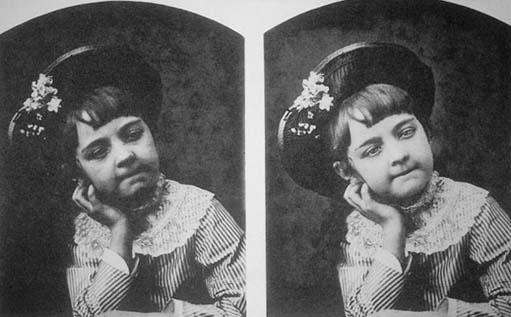

In addition to the efforts made before exposure to show sitters at their best, portrait photographers regularly retouched the negative to remove or improve any perceived defects or blemishes. Before the 1860s, in Britain retouching was generally criticized for interfering with the ‘truthfulness’ of the photographic image. By the mid-1860s, however, the issue became the subject of intense debate and discussion and the journals published details of the various techniques available at the time. Retouching became an established component of commercial practice, though a small minority of purists continued to denounce it. Image 39, from the frontispiece of an early manual on retouching, shows a before-and-after portrait intended to demonstrate the benefits of the practice.

Two photographs of a child, before and after retouching

By working on the negative photographers could tone down or remove spots, freckles, warts, bags under the eyes and double chins, reduce waists, neaten figures and make those adjustments necessary to satisfy the concerns of both photographer and sitter. A certain amount of retouching would be undertaken as a matter of course, such as the removal of blemishes or freckles. The issuing of proof prints before the final order gave customers the opportunity to suggest any adjustments they would wish to have introduced.

Retouching was not confined to the negative. Work could also be undertaken on the surface of the photographic print. This was common on enlargements. As the retouching medium can age differently from the print surface these touches can often appear obvious and crude today.

4.11 Colouring

A photograph of a child

The photographic print could also be ‘improved’ by the application of colour on the surface of the finished print. In the 1840s painters of miniature portraits, who faced redundancy after the introduction of photography, sometimes found employment hand-colouring daguerreotypes. The colouring of portraits commanded an additional charge and suggests that pictures chosen for colouring held a special significance for their owners. In the average high-street studio, the colourist never normally saw the original. Simple written instructions accompanied the print: eyes, blue; hair, brown; dress, green. The colour artist did whatever was necessary.

This is probably a good place to note that the tonal translation of colour in 19th-century photography was incorrect. Blues and violets usually translated too light, so skies were a constant problem. Yellows and reds, however, translated too dark. A blue-eyed blond with freckles could present real problems! So it's never a good idea to infer colours from early black and white photographs. Orthochromatic negatives were introduced towards the end of the 19th century.

4.12 Key concepts

We can conclude that the ideas relating to idealization, positive characterization and sexual stereotyping had a significant influence on the treatment of all 4 components of the portrait: expression, pose, background accessories and lighting.

Victorian family photographs (like most other primary sources) are therefore selective, partial and biased. Early photographers regarded it as part of their proper function to emphasize those aspects that were considered at the time to be good and conceal those regarded as bad. It was no part of their duty to uncover or present the ‘real picture’.

You can sometimes learn more of the ‘real’ story behind the image when you interview relatives who appear in the photographs. Photographs can play a useful role in oral history interviews by

sparking recollection. But tread carefully – some photographs may be invested with great emotional significance for their owners.

5 Camera culture

5.1 Capturing commemorative events

This section explores the events commemorated in photographs.

Activity 19

Begin by listing the occasions when we choose to use our cameras today. It might help to think back over the times when you have used your camera in the last 12 months.

Answer

Does your list include some or all of the following?

holidays

outings

weddings

christenings

anniversaries

visits from or to relatives

family reunions

sports days and performances

visits by important people

new car, new house, new baby

national events: jubilees, street parties

local carnivals and street parades

works outings and events

festivals, e.g. Christmas

birthday parties

pets.

Activity 19a

Now see if you can assign the various occasions to one of the following categories:

rites of passage

special occasions and celebrations

prized possessions.

Answer

You may have thought of occasions which do not fall within my categories, but I hope you found that the majority of them can be assigned to those headings. So we can assert that in general the majority of snapshots taken in Britain in the early 21st century celebrate special occasions.

This activity reveals that, even today, our family photographs provide only a selective and partial record. Most of us don't bother to photograph the routine, ordinary aspects of our everyday lives. What, then are the consequences of neglecting the mundane in favour of the special? Are we continuing to portray an idealized version of family life following traditions inherited from the past? To answer this we need to look at the occasions when our ancestors chose to be photographed.

We might also want to think about changing our practices. Once we realize that we are working within a set of inherited and unexamined conventions, we may want to challenge them. We might, for example, decide to use the camera to record the mundane, or to comment on aspects of our personal lives about which we feel strongly and have something to say.

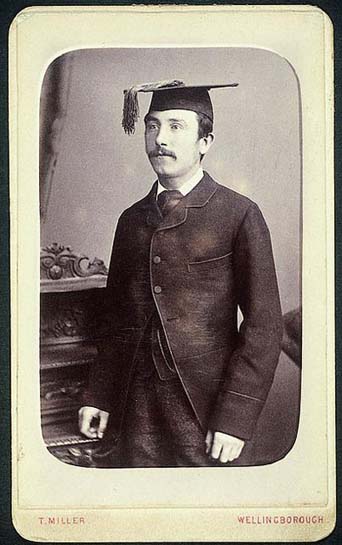

5.2 Records of achievement

A photograph of a male wearing a mortar board

The Victorian family album validated success. In keeping with the theme of idealization, our ancestors courted the camera to commemorate events and achievements that brought credit to the individual and reflected glory on the family. Evidence of delinquency or failure was excluded or rigorously edited.

Portraits of the new graduate in gown and mortar, the mayor in robes, or the uniformed policeman displaying the latest stripe or badge provided visible proof of career success and achievement in the workplace.

Successful sportsmen and women changed into the appropriate kit at the studio and posed surrounded by the cups, medals, awards and distinctions gained in competition.

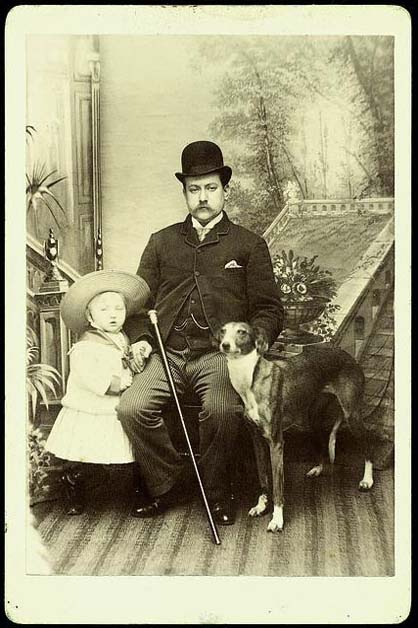

5.3 Prized possessions

A photograph of a man, child and dog

Prized possessions also feature in the family album. Family pets, cats and dogs were frequently taken to be photographed in the studio and often appear in portraits taken outside the home. Some photographers advertised equestrian studios where horses could be photographed. Bicycles, motor-cycles and motor cars proved popular in later years.

5.4 Special occasions

Helene Witte in her gown for a fancy dress ball

Special occasions could include events of family, local or national significance. Those wealthy enough to attend important balls and dances would often visit the studio and change into their ball gown or suit for the portrait. Local events could include amateur dramatics when sitters would attend the studio to be photographed in costume. Whit week processions in northern towns required each child to have a new outfit. So children would be taken to the studio before the parade and would probably be photographed again later in the day as part of a group in the procession. National events such as coronations and royal anniversaries often provoked an appearance in front of the camera.

Similarly it was customary for people to visit the photographer whenever they went on holiday, whether on visits to friends or relatives, or on a day-trip to the seaside. Even those who stayed at home visited the wakes and fairs which were sure to include numbers of photographers ready to take advantage of the free-spending mood engendered by the holiday feeling.

5.5 Rites of passage

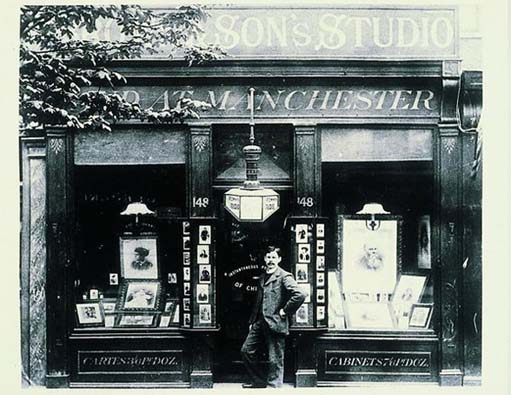

William Arthur Brown, the son of James Brown standing in the doorway of Brown & Sons Studio, 148 Camberwell Road, London

Most portraits, however, were taken to celebrate rites of passage, such as christenings, comings of age, engagements, weddings and anniversaries. The photographs bore witness to a successful progression through life, provided eloquent testimony to the social conformity, virtue and respectability of the Victorian family, and provided ample opportunity to flaunt wealth and possessions. Because the photographs were taken in the studio they were not documentary in character. They tell us little or nothing about how the occasion was celebrated, only that the family regarded the occasion as significant.

Most family historians want to discover the identity of the sitters. Our ancestors rarely troubled to put names to portraits. Why should they bother when they knew their own relatives? (A reminder to us to be diligent in recording details about our own photographs!) You will be better placed to solve this difficult problem if you can identify the occasion celebrated in the portrait and can link that occasion with an approximate date for the photograph. The studio's location can also help. So if you have a wedding portrait taken in the early 1870s in the Chester area you may be able to assign possible identities using information found in marriage registers or census records.

We need to spend some time now seeing if we can identify the occasion behind the portrait. This is not always as easy, since the visual subtleties are often now lost to us and we have ceased to observe some of the rituals of the past.

Obviously those rites of passage which required distinctive dress are the easiest to recognize, so let's start with an easy one.

5.5.1 Christening

Photograph of a woman with a baby

The christening dress here identifies the occasion.

In the normal course of events, Victorian couples would produce their first baby within a year or so of the wedding. Christening usually took place anything from 4 to 8 weeks after the birth.

In rich Victorian families christenings could be elaborate affairs emphasizing the high social rank into which the infant was born. The christening robe itself could represent a lavish statement of family fortunes. Great care was usually taken to display the robe to best advantage in the portrait.

New babies were pictured with their mothers and in the case of wealthy families with their nurses. Nurses often wore uniforms, but not always. So we must not assume automatically that the woman with the baby was its mother.

5.5.2 Skirts and breeching

Look carefully at Images 46, 47 and 48.

A photograph of a child

A photograph of a child

A photograph of a man and a child

Victorian and Edwardian boys and girls were dressed in skirts in their early years. Boys were ‘breeched’ between the ages of about 3 and 5 – that is, they were put into their first pair of short trousers. Families must have been extremely proud on this occasion because photographs documenting this change of status survive in great number. Diaries, too, often record occurrences of breechings in the family.

Without the manuscript information on the reverse of Michael Seymour's portrait (Image 46), we may have had difficulty identifying the sex of the child. Toys and accessories can sometimes provide useful clues. Whips, hoops and guns are the accoutrements of (guess who?) little boys; dolls are the usual companions of little girls. (Michael Seymour is holding something but I cannot make out what it is.)

Boys in breeching portraits (Image 47) could be photographed on their own, as in the portrait of Douglas Matthew Watson. Douglas was nearly 3 when his sartorial transformation took place. Sometimes the breeched boy appeared with other members of his family including parents and/or siblings.

5.5.3 Birthdays

Photograph of a woman with a child

A photograph of a child

A photograph of a child

A photograph of a child

Photographers encouraged mothers to bring their children to be photographed each year around the date of their birthday as this was seen as the best way of keeping a record of their progress and development. Images 49–52 are photographs of Max Witte whose mother took him on regular visits to the superior studio of the Manchester photographer Warwick Brookes. Max's father was a German emigré and highly successful shipping merchant. The family lived in Bowdon in Cheshire.

Some photographers actually issued birthday albums to encourage annual visits. The album itself is sometimes featured as an accessory in later portraits. The society photographer Richard Speaight made particular reference in his autobiography to the mother of Myrtle Farquharson, who brought her child to his studio 2 or 3 times a year – thereby implying that such behaviour was the exception rather than the rule.

In low-income families, of course, the state of the family finances would have determined the frequency of visits to the photographer.

5.5.4 Confirmation

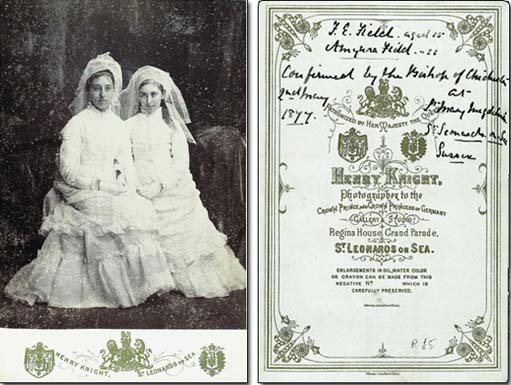

A photograph of two girls

You may find it difficult to read the verso text, so here it is for you.

The handwriting reads: F.E. Field aged 15; Amynora Field aged 11. Confirmed by the Bishop of Chichester 2 May 1877 at St Mary Magdalenes, St Leonards on Sea, Sussex.

The printed text reads: Cabinet by Henry Knight. Patronized by Her Majesty the Queen, Photographer to the Crown Prince & Crown Princess of Germany

The girls in this photograph are not bridesmaids, as I thought on first seeing this photograph. The photo celebrates confirmation. Confirmation was an important and serious event for many teenagers in Victorian Britain, as their surviving diaries can testify. Young people were confirmed in great swathes. Age at confirmation was often determined by the timing of a bishop's visit.

5.6 Rites of passage (continued)

5.6.1 Young adults

Activity 20

Look closely at Images 54 and 55. Can you identify the two features which distinguished a girl from a young woman in the Victorian and Edwardian period?

Answer

To mark the important transition from childhood to adulthood, young women put their hair up and let their skirts down. Dress can sometimes assist in guessing the age of young females. One influential authority felt that a girl of 13 or 14 could look much older in her portrait if it was not taken to show that she is still a young girl. He advised fellow photographers to make a point of featuring the short frock which showed a girl's ankles.

The daughters of the wealthy were presented at Court. These Drawing Room Presentations were governed by strict regulations. After the nobility and squirearchy only certain professions were admitted – the daughters of the clergy, of naval and military officers, of physicians and barristers. This important occasion required special dress, entailed considerable expenditure and was usually celebrated by a photograph at one of the elite London studios. Presentation dress had to display a number of obligatory features: low décolletage, short sleeves; a full train fastened at the waist and an ostrich-feather head-dress.

5.6.2 Engagement and marriage

Of all rites of passage celebrated in the Victorian family album, those taken at the time of engagement and marriage are by far the most numerous. This testifies to the importance vested in marriage by the Victorians. The custom of commissioning oil or miniature portraits at the time of an engagement or marriage was well established before the advent of photography. Photography enabled couples on more modest incomes to indulge a practice that became widespread among working-class families by the 1880s.

Since the treatment of engagement and marriage portraits was so similar it can be difficult to distinguish between them. We shall deal with them together for this reason. Family circumstances would, of course, dictate whether the individuals could afford to commemorate both events with a photograph.

Photograph of an unknown woman in a wedding dress

By the middle of the 19th century, high society weddings had become fully-fledged social extravaganzas involving enormous expense and considerable planning. The white wedding dress was a Victorian introduction but remained largely confined to the wardrobes of the rich and privileged. The choice of the exclusive studio of Elliott and Fry confirms that the young woman in Image 57 belonged to a wealthy family.

Activity 21

A wedding portrait

Do you remember the wedding portraits we looked at earlier (Images 27 and 28)? The majority of Victorian brides wore the best day-dress they could afford. So although Image 58 appears at first sight to be no more than a studio portrait with conventional props and accessories, it is, in fact, a wedding photograph. By the 1880s, buttonholes and flowers start appearing in these portraits, providing supporting evidence of the occasion.

Does any other element of Image 58 suggest an engagement or wedding?

Answer

Notice the careful display of the woman's newly-ringed finger. Many of the poses adopted in wedding and engagement portraits give prominence to the ring. So always pay particular attention to the woman's hand. A magnifying glass can be useful.

By the late 1880s it was suggested that the pose of the seated gentleman and lady standing with her hand on his shoulder had become the particular hackneyed hallmark of the engaged or married couple. However, it is worth noting that in many examples the woman is seated while the man stands beside her. This should be seen as evidence of their respective heights rather than any comment on the politics of sexual power in the 19th century. Photographers were concerned to get both heads into a relatively narrow field of focus. This meant bringing them closer together while maintaining a balanced composition. If a tall man was seated, his head was brought into focus with that of the shorter woman beside him.

There were variations on the wedding/engagement theme which are easy to spot – if you are looking out for them.

Photograph of a woman

Photograph of a man

Photograph of a man and a woman

Images 59, 60 and 61 were clearly taken on the same occasion. They demonstrate that the placing of photographs in the album can be significant. It is good practice to keep a careful record of the arrangement as you originally found it.

Photograph of a man and a woman

Photograph of a group of women

We know from family records that Image 62 was an engagement portrait. It was taken by the woman's father, Frederick Batho, a commercial portrait photographer with a studio in the Cheetham Hill area of Manchester in the 1890s (Image 63). I like the symbolism of the balustrade dividing the engaged couple who are not touching one another – though am not so keen on the fact that she has been placed slightly behind her intended!

A wedding portrait

Couples in the 19th century were photographed around the time of the wedding but I cannot be more precise than that. Oral evidence confirms that it was customary in the first half of the 20th century for couples to attend church to get married and then proceed to the photographer's studio for the wedding portraits. By that time photography had become an integral part of the ritual. There are tales from this date of newly-weds arriving at the studio to find themselves at the end of an enormous queue and deciding to come back the following Saturday rather than endure a long wait. This fate may have befallen the couple in Image 64, for on the back of the mount in manuscript are the words: ‘Our wedding taken week after wedding Feb 11th 1886’. The portrait appears to include the bridesmaids.

5.6.3 Honeymoons

A photograph of a couple on their honeymoon

After marriage came the honeymoon – but only for the affluent. Few among the working classes could afford a honeymoon, so the honeymoon portrait immediately conferred prestige.

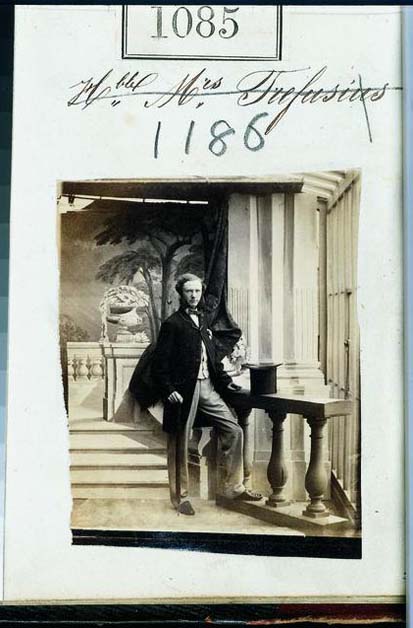

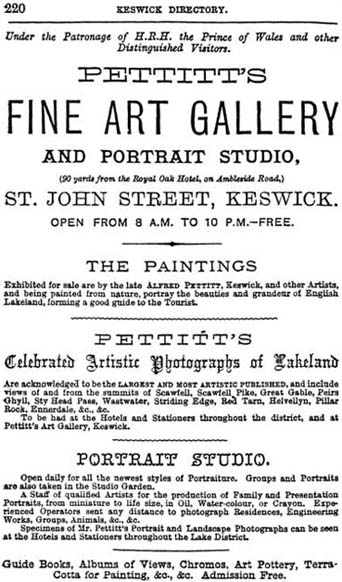

By the early 19th century, fashionable middle-class couples would begin their honeymoon trips immediately after the wedding, unaccompanied by other relatives. The completely private honeymoon only became wholly fashionable in the Victorian era when the idea of marrying for love was an accepted ideal. Since the middle classes sought status by aping the very rich, they too began to take honeymoons. The very rich travelled to Europe, while the comfortable classes visited the Lake District or the Isle of Man. Ben and Carrie, the couple in Image 65, had their honeymoon portrait taken in Pettit's. (Image 66 shows an advertisement for Pettit's Fine Art Gallery in the Lake District.)

5.6.4 Wedding anniversaries

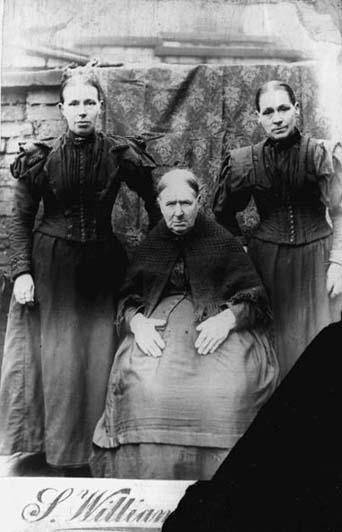

Silver and golden wedding anniversaries were often commemorated with a portrait. Many examples follow the pattern of the studio portraits taken for engagements and weddings, with the couple taken individually and together.

Photograph of a woman

Photograph of a man

These portraits would have been carefully designed to face each other in an album.

There is another common treatment where the anniversary couple was portrayed surrounded by their children. Such portraits regularly excluded sons- and daughters-in-law, as in Image 69.

5.7 Rites of passage (continued)

Death

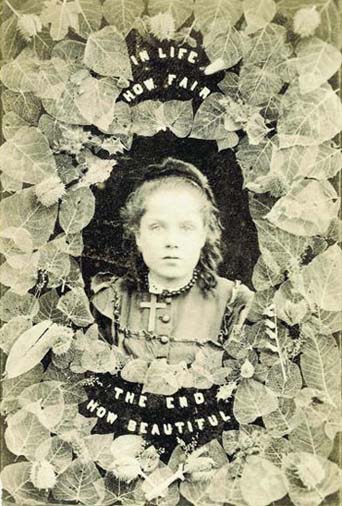

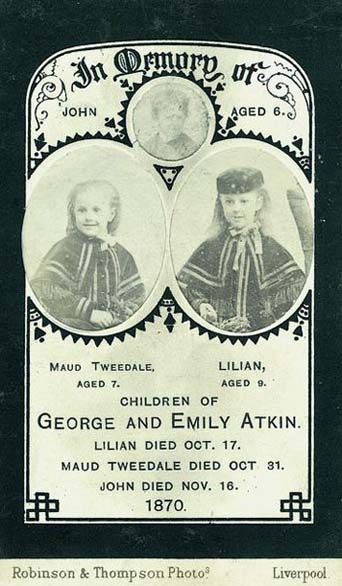

The final rite of passage, death itself, permeates the Victorian family album. Throughout the 19th century it was common practice, following the death of a relative, to commission memorial photographs. The overwhelming majority of these memorial photographs feature the person as living, not dead.

A photograph of a goal with the words ‘In life how far, the end how beautiful

A memorial photograph

The memorial photograph assumed a wide variety of different guises depending on the needs and circumstances of the grieving relatives. They could vary from simple cartes de visite, like Images 70 and 71, to framed enlargements on opal glass. Identification of the memorial nature of a portrait is easy when it was issued on special mourning cards complete with black banding at the edges and suitable phrases such as ‘In memory of’, ‘Affectionate remembrance’ and so on. However, that was not always the case.

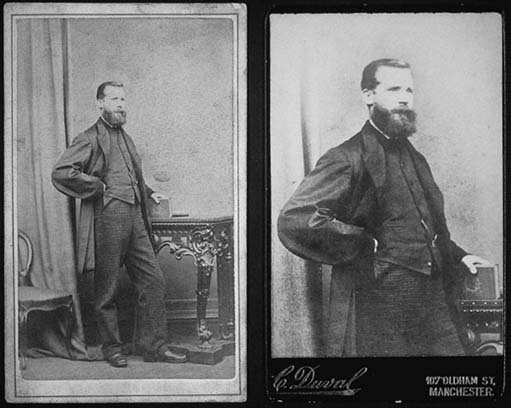

Two photographs of a man

Can you see the connection between these 2 portraits, which came from the same album?

The three-quarter length portrait on the right has clearly been copied from the earlier, full-length portrait. The earlier print dates to the 1860s/70s, the later print to the 1890s. We know the copy print was not taken from the original negative because it isn't sharp. Although it carries no obvious identification, the copy print is probably a memorial photograph, produced after the man had died, for distribution to members of his family. When looking through your own albums, be alert for examples like this.

5.7.2 Post-mortems

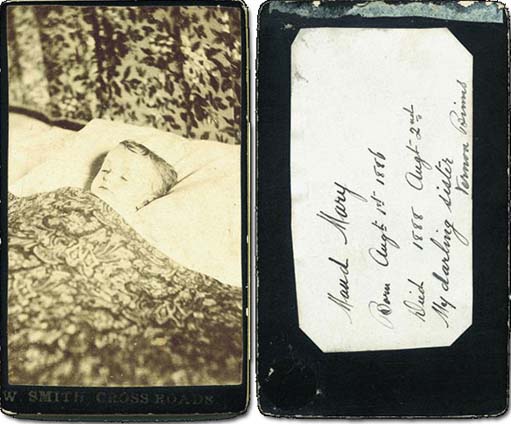

Activity 22

How do Images 73 and 74 differ from the usual studio portraits of children? Make a note of the more obvious differences.

Answer

The children have their eyes closed. They appear to be posed in some sort of arrangement of blankets or covers. The backgrounds and accessories (or what you can see of them) don't conform to the usual pattern.

A tiny minority of people in Victorian Britain commissioned post-mortem portraits. Post-mortem portraits were usually taken in the family home. In all aspects of the posthumous portrait, such as the positioning of the body, the arrangement of draperies and lighting of the face, the aim was to soften the hard realities of death and suggest instead the tranquillity of sleep.

The purpose of the post-mortem photograph was to act as a palliative. Just as they sought to idealize in portraits taken from life, so Victorian photographers consciously attempted to ameliorate the uncompromising reality of death by suggesting a kinder, gentler, more familiar state of being. Such a picture was justified on the grounds that it would help dispel sorrow and bring solace and comfort in its place.

A photograph of a child

Image 75 is the post-mortem portrait of Mary Maud Binns, presumably photographed in bed in the family home. Although the inscription on the verso gives the date of death as 2 August 1888, her death certificate records that she died of pneumonia on 21 September 1888. (Remember the importance of checking apparently reliable sources.) Maud's father was a grocer and the family lived at Cross Roads, Bingley, near Keighley in Yorkshire. The photographer, W. Smith, was local and therefore readily available. His work suggests that he was not a high-class operator.

6 Portraits in the open air

6.1 The rise of the itinerant photographer

Happily, not all early family photographs were taken inside conventional studios. Sitters were frequently photographed in the open air or in temporary, makeshift studios. Portraits were taken in the street, at the fairground, at the seaside, at local beauty spots and in the parks and commons where town dwellers went for relaxation and entertainment on Sundays and holidays. Itinerant photographers who worked these venues would set up shop for the day, the week or longer, depending on situation and circumstance.

A photograph of two people

Photographers could exploit a clientele of day-trippers and temporary visitors by offering a while-you-wait service. For this they employed a process known as the wet collodion positive. A sheet of glass was coated with sticky collodion, immersed in the light sensitive silver nitrate and exposed in the camera while still wet. (It remained sensitive only while it was wet.) The exposed plate was chemically processed and then bleached. When placed against a black background (or coated with Bates's Black Varnish) the image appeared positive. The absence of the need for daylight printing speeded up and simplified the process. For a small additional charge, the glass plate was housed in a case or frame. The whole procedure took about 5 minutes from beginning to end. In Britain these images became known as cheap glass positives; in America they were called ambrotypes. Image 76 is an example of this.

A photograph of a man

The glass positive was gradually supplanted by the ferrotype (also called tintype). In the ferrotype the glass base was replaced by a thin sheet of enamelled iron. The ferrotype was cheaper and less liable to break but also generally poorer in quality since the highlights were rarely white. Since there was no negative involved in the process the ferrotype images were usually laterally reversed. However, ferrotypes could be produced in multiple copies using cameras with multiple lenses and scissors to cut the thin sheets of iron after exposure and processing. The ferrotype became popular in Britain from the 1870s.

A photograph of someone photographing a group of people.

There was great variation in the equipment used by different itinerants. Basic necessities included a camera, tripod and some form of dark box (usually on wheels) in which to sensitize and process the negative. Dark boxes could be crude adaptations of prams or market barrows, or neat, purpose-designed, business-like constructions.

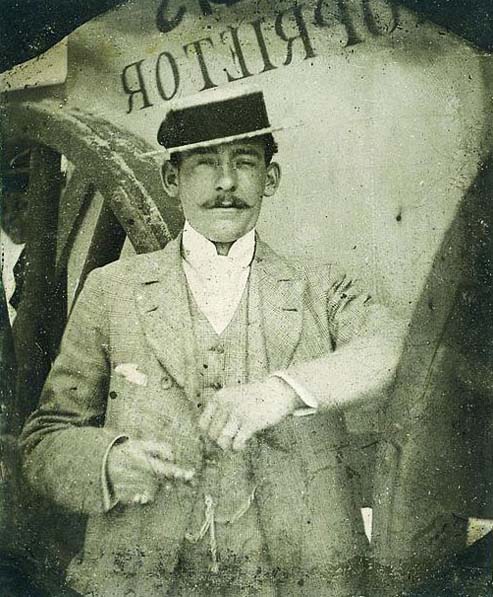

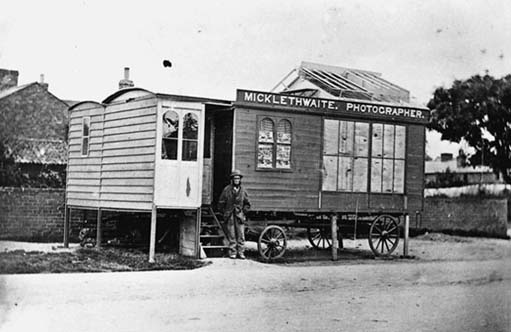

Micklethwaite's gallery on wheels

Some itinerants could afford to invest in horse-drawn caravans which combined living accommodation with glazed studios and darkroom facilities. These vans were moved from venue to venue by horses hired for the journey. The wooden structure to the left of the steps into Micklethwaite's studio (Image 79) was a temporary extension which would have been dismantled and stored while the van was on the move.

Other itinerants worked in canvas tents pitched on the sands or in the fairground.

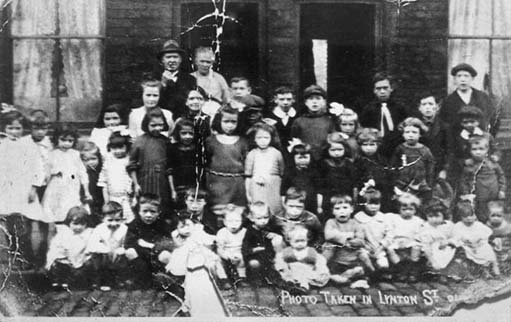

The beach at Bridlington

There was a similar variation in the pattern of itinerant activity. Some studio proprietors might take to the road in the summer months and some itinerant photographers might take up entirely different occupations to tide them over the winter months. Itinerant operators usually worked on spec rather than to commission and they were frequently regarded with contempt by established studio proprietors with good connections.

We are going to devote a little attention to outdoor work in the street and at the seaside, as these venues feature prominently in the typical family album.

6.2 Street photography