Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 28 January 2026, 9:27 PM

Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus

Introduction

This course is on Christopher Marlowe's famous play Doctor Faustus. It considers the play in relation to Marlowe's own reputation as a rule-breaker and outsider and asks whether the play criticises or seeks to arouse audience sympathy for its protagonist, who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for 24 years of power and pleasure. Is this pioneering drama a medieval morality play or a tragedy?

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in the Arts. You might be interested in a more recent Open University course, A111 Discovering the arts and humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

read closely – analyse a passage from the play

examine genre – what kind of play is Doctor Faustus?

consider themes – what are the main themes or issues explored in the play?

read historically – what are some of the connections between Doctor Faustus and the historical period in which it was written?

read biographically – what, if any, insights does Doctor Faustus give us into the character and reputation of its author?

1 Christopher Marlowe

1.1 Marlowe: the man

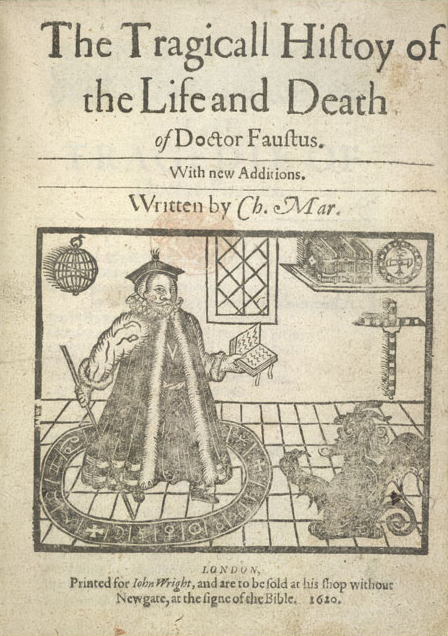

In this course I will discuss the question of reputation in relation to a literary text, Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, which was written sometime between 1588 and 1592 and was first published in 1604 (the A text). We will start by considering the literary reputation of Marlowe (1564–93), who lived and wrote at the same time as Shakespeare and is probably the most famous of his many gifted fellow writers.

We will then look at Doctor Faustus, Marlowe's most well-known play. The main aim being to introduce you to the study of literature at undergraduate level. We will discuss several aspects of the play, and engage in some of the main skills and techniques involved in the analysis and interpretation of literary texts.

Let's begin by looking at the life and reputation of the play's author.

Marlowe's touch was in my Titus Andronicus, and my Henry VI was a house built on his foundations … I would give all my plays to come for one of his that will never come.

These lines come from John Madden's 1998 film Shakespeare in Love. Shakespeare, played by Joseph Fiennes, has just heard that Marlowe has been stabbed to death in a tavern in Deptford and believes, mistakenly, that he is responsible for his death. Stricken with guilt and grief, he acknowledges the immense artistic debt he owes his great contemporary, without whose works he feels he could never have written two of his own early plays.

This scene from the film gives us a reasonably accurate picture of the kind of reputation that Marlowe now enjoys as a writer: he is seen both as an important dramatist in his own right, and as a pioneer whose achievements on the stage made possible the considerable accomplishments of his successors, most especially the plays of Shakespeare. What Shakespeare in Love only hints at in its mention of Marlowe's sticky end is that he is as famous for his life and death as for his works.

Marlowe's posthumous literary reputation was heavily influenced by several hostile contemporary accounts of his character and beliefs. His fellow playwright Thomas Kyd accused him of holding a variety of ‘monstrous opinions’, of being ‘intemperate’ and of having ‘a cruel heart’ (Maclure, 1979, pp. 35, 33), though it's important to realise that Kyd made these claims under torture. The spy Richard Baines, who had already informed on Marlowe during the counterfeiting affair, submitted a report to the authorities which portrayed him as a scoffer and heretic who, for example, mocked religion as a tool used by the powerful ‘to keep men in awe’ and said ‘Christ was a bastard and his mother dishonest’ (ibid., p. 37). Baines also accused Marlowe of what we would call homosexuality (the word did not exist in the sixteenth century, though buggery was punishable by death) when he attributed to him the view that ‘all they that love not tobacco and boys were fools’ (ibid., p. 37). The puritan Thomas Beard charged Marlowe with ‘atheism and impiety’, with denying ‘God and his son Christ’ (ibid., p. 41). He also interpreted Marlowe's violent death as God's judgement upon his sins, or as Beard put it rather more colourfully, as the ‘hook the Lord put in the nostrils of this barking dog’ (ibid., p. 42). It's only fair to add that Marlowe was also admired and celebrated as a poet and dramatist during and immediately after his lifetime; for example, fellow dramatist George Peele called him ‘the Muses' darling’ (ibid., p. 39), while another playwright, Thomas Heywood, writing in 1633, described him as ‘the best of poets in that age’ (Cheney, 2004, p. 3).

Given such spectacular biographical material, it's not surprising that Marlowe the man has always been as famous as Marlowe the writer. Moreover, the correlations between the work and the life (both the facts and the gossip) are undeniably striking: all of Marlowe's dramatic protagonists are in some significant sense rule-breakers, who challenge religious, political or sexual orthodoxies, much as he was accused of doing. Two of his most well-known heroes, Tamburlaine and Doctor Faustus, share with their creator their rise from low-class origins to fame and success, while another protagonist, King Edward II, is sexually infatuated with his favourite Piers Gaveston.

Marlowe's literary reputation has depended to a considerable extent on how different historical periods have viewed his life and his unconventional protagonists. Those critics in the eighteenth century who had some knowledge of Marlowe were generally scandalised by the biographical accounts that survived and repelled by what they perceived to be the intemperate nature of his protagonists. It was not until the nineteenth century that a more favourable view of Marlowe's artistic accomplishments began to emerge. The establishment of English Studies as a distinct academic discipline in the second half of the nineteenth century brought with it the construction of a canon of great writers and a history of English literature which accorded Marlowe the crucial groundbreaking role he plays in Shakespeare in Love.

Changing views of the artist consolidated his integration into the literary canon. Viewed in the light of the biographies of romantic poets like Shelley (1792–1822), an avowed atheist, and Byron (1788–1824), surrounded through much of his career by sexual scandal, Marlowe's tumultuous life and early death, along with his sensational plays, began to look less like culpable immorality and more like evidence of poetic genius. As the figure of the artist became increasingly associated with rebellion and excess, so the life and work that once disqualified Marlowe from literary celebrity came virtually to guarantee it.

1.2 Doctor Faustus

Critics who have studied Marlowe's work have for the most part been inclined to take on trust the picture of him provided by Kyd, Baines, Beard and others, and to read the plays as statements of the author's own radical beliefs. But there is an obvious problem with this approach to Marlowe's work: we simply don't know whether these hostile accounts of his opinions are accurate or, as seems likely, deeply compromised by their writers' own motives and circumstances.

Doctor Faustus is the most famous of Marlowe's plays, and its hero, who sells his soul to the devil in return for twenty-four years of power and pleasure, is by far the best known of his rebellious protagonists. Marlowe based the plot of his play on The History of the Damnable Life and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus (1592), an English translation of a German book (now known as the Faustbuch) about an actual historical figure who gained notoriety in early sixteenth-century Germany by dabbling in the occult. This story rapidly became the stuff of legend and, like most legends, it has been subject to numerous retellings, including the two-part play Faust (1808; 1832) by the German writer Goethe, the novel Doctor Faustus (1948) by Thomas Mann, and Peter Cook's and Dudley Moore's 1967 film Bedazzled (remade in 2000), which adapted the legend for comic ends.

Why did Marlowe choose to adapt the Faust legend for the stage? Was the free-thinking dramatist, as numerous critics have speculated, attracted to a story about a man who rebelled so flagrantly against the Christian God? One of the interesting questions to ask about Doctor Faustus is whether the play seems to strengthen or undermine the longstanding view of Marlowe as a maverick artist, and we will return to this question at the end of the course.

1.3 Reading a Renaissance play

If you have never read a Renaissance play before – and even if you have – you may well find Doctor Faustus a challenging read. This is chiefly because, like the plays of Shakespeare, Doctor Faustus was written during the historical period known as the Renaissance (or the early modern period), when the vocabulary was significantly different from twenty-first-century English. It is also written largely in blank verse, a term that requires a few words of explanation. Look for a moment at the four opening lines of Doctor Faustus:

Not marching now in fields of Trasimene

Where Mars did mate the Carthaginians,

Nor sporting in the dalliance of love

In courts of kings where state is overturned … (Prologue, ll. 1–4)

If you count the syllables in these lines, you will find that each one contains ten syllables. If you read the lines aloud, you will hear that for the most part every other syllable carries a particularly marked accent:

Not march|ing now | in fields | of Tra|simene

Where Mars | did mate | the Car|thagi|nians,

Nor sport|ing in | the dal|liance | of love

In courts| of kings| where state| is o|verturned

The second line doesn't fit all that comfortably into the overall pattern because it feels a bit awkward giving a strong stress to the last syllable of ‘Carthaginians’. But we can still say that, roughly speaking, each line of verse has five stressed and five unstressed syllables, and that these are arranged in a fairly regular pattern of unstressed/stressed. In poetry this pattern, or metre, is called iambic pentameter, which is generally thought to be the poetic metre that most closely reproduces the cadence of English speech. This is also blank verse because, in addition to being written in iambic pentameter, the lines are unrhymed. Marlowe was known and admired by his contemporaries for the skill with which he used blank verse in his plays.

Don't worry if this discussion of metre is new to you: its purpose is just to make you aware that the play's verse has an underlying rhythm. This rhythm is mainly determined by the metre which, as we have just seen, is more regular at some points than others, but it is also affected by punctuation, which can slow the verse down (if there are a lot of stops and pauses) or speed it up (if there are few of these).

Everyone has their own way of reading, but I would suggest, especially if this is your first encounter with Renaissance drama, that when reading the play you focus on the story: try to get the gist of what happens, who the main characters are and what they do. Don't worry if you find this hard going or feel that you do not understand it all. Remember that reading early modern English is challenging, and that in the second part of this course we will be looking more closely at particular parts of the play.

If you have not already done so, please read Doctor Faustus now.

I would suggest that you leave the Doctor Faustus document open on your desktop to gain the maximum benefit from the discussions that folow.

2 Reading Doctor Faustus

2.1 Act 1, Scene 1: "Yet art thou still but Faustus, and a man"

2.1.1 The morality play

Before looking at the play's opening scene I should add a brief note on the medieval morality play, the type of drama on which Marlowe draws in adapting The Damnable Life for the stage. After the Prologue and Faustus's long opening speech, you may have been startled by the appearance of the Good and Evil Angels. Even if you had expected to find supernatural beings in a play about a man who sells his soul to the devil, the Good and Evil Angels may have struck you as strange, perhaps because they are not what we expect characters in literary texts to be like. Their names tell us pretty much everything we need to know about them for, rather than having individualised personalities, they represent abstract moral qualities – in this case, goodness and evil. At this point and throughout the play they are engaged in a struggle for the soul of Faustus, the Good Angel warning him of the danger of arousing ‘God's heavy wrath’ (Act 1, Scene 1, line 74 – displayed as 1.1.74) by practising black magic, the Evil Angel egging him on by reminding him of the power that necromancy will bring him.

This way of creating characters, or characterisation, is typical of morality plays, which are fundamentally religious dramas that enact the conflict between good and evil, each of which is embodied in supernatural figures (like Mephistopheles and Lucifer) or personified abstractions (like the Good and Evil Angels and the Seven Deadly Sins). They are shown fighting for the soul of a central human character who often represents humanity itself, hence the title of one of the best-known morality plays, Everyman. The aim of the morality play was primarily didactic; that is, it sought to teach its audience, and to offer moral and spiritual lessons about how to live a good Christian life. In Doctor Faustus, this didactic element can be seen most clearly in Marlowe's use of a Chorus to present a Prologue and Epilogue that, rather like the Choruses of ancient Greek tragedies, express traditional attitudes and guide the audience's response to the play. (In Greek tragedy the Chorus was a group of people, whereas in Doctor Faustus and Elizabethan drama generally, it is one person.) Yet morality plays also sought to entertain their audiences; they are full of clowning and knockabout comedy, just as in Doctor Faustus.

Morality plays were prevalent in England during the late Middle Ages, but were still popular when Marlowe was writing. The fact that he turned to the morality play when he came to dramatise The Damnable Life raises questions about the genre of Doctor Faustus: what kind of play is this? Is it essentially a late sixteenth-century morality play, warning its audience of the dire consequences of practising black magic? Or is its attitude to the story it tells more complicated than this? How does the play encourage us to respond to the central character who sells his soul to the devil?

Activity

We can begin to answer those questions by looking at the Prologue. Please reread the speech now, and then write a brief summary of it, no more than four or five sentences. What main points would you say the Chorus is making here?

Discussion

Here is what I've come up with:

The Chorus spends several lines telling the audience what the play is not about – war or love or martial heroism – before he tells us what it is about: ‘Faustus' fortunes, good or bad’ (l. 8).

Then he tells us about Faustus's childhood, specifically that although he was born to ‘parents base of stock’ (l. 12), he went on when he was older to study divinity at the University of Wittenberg, where his intellectual brilliance led swiftly to his being awarded a doctorate.

In line 20, the tone of the speech seems to change, as the Chorus speaks of Faustus's ‘cunning of a self-conceit’, which has been explained as ‘intellectual pride engendered by arrogance’.

The Chorus goes on to explain that his intellectual pride led Faustus to take up the study of magic, or ‘cursèd necromancy’, despite the fact that it jeopardises ‘his chiefest bliss’ (l. 27); that is, his chance of being granted eternal salvation when he dies.

The Chorus, then, is kicking things off by giving us a brief biography of the play's protagonist. I hope you agree that the picture of Faustus it offers us is a mixed one. The Chorus undoubtedly condemns Faustus's study of magic and encourages us to disapprove of it too. But the speech also registers the greatness of a man who, through his own merit, overcame the considerable disadvantage of lowly birth to rise to the pinnacle of his profession.

Let's look a little more closely now at the last eight lines of the Prologue. When the tone of the speech changes in line 20, the Chorus says not just that Faustus is full of intellectual pride and arrogance, but that he is ‘swollen’ with it. This is easy for us to understand, for we still use the expression ‘swollen head’ to describe someone who thinks too highly of himself. We also understand that the Chorus is not using the adjective ‘swoll'n’ literally; it is not that Faustus is actually swollen up, but that he has an inflated opinion of himself. In other words, ‘swoll'n’ is used in a figurative rather than a literal way. Figurative language describes one thing by comparing it with something else. The two most well-known types of figurative language are similes and metaphors. Similes make a direct comparison by using the word ‘like’ or ‘as’. If Marlowe had written ‘Till, swoll'n like a balloon with cunning of a self-conceit’, he would have made a direct comparison between Faustus's pride and an inflated balloon. But he chose to use not a simile but a metaphor, with the result that rather than being likened to a particular inflated object, pride is identified more broadly with the condition of being swollen.

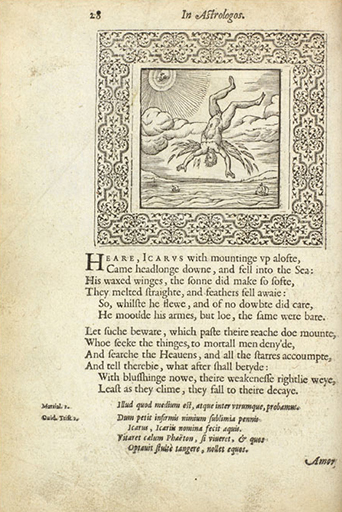

This metaphor is followed by the lines: ‘His waxen wings did mount above his reach, / And melting heavens conspired his overthrow’ (ll. 21–2). This is an allusion to the ancient Greek myth of Icarus, who attempted to escape from Crete with a pair of waxen wings, but flew too near the sun and plunged to his death when the sun melted the wax (see Figures 2 and 3). He became the symbol of the ‘overreacher’, of the man who tries to exceed his own limitations and comes to grief as a result. Like Icarus, in the Chorus's view, Faustus tried to ‘mount above his reach’ and was punished for his presumption: ‘heavens conspired his overthrow’ (l. 22). This is an intriguing twist on the Icarus myth; for whereas Icarus's pride seems to be self-destructive, Faustus's sparks the intervention of a deity who ‘conspires’ to destroy him.

It is interesting to compare Brueghel's treatment of the myth with that of Marlowe's Chorus and Whitney's emblem. Icarus, just visible in the bottom right of the painting as he sinks to his death in the sea, is unnoticed as the rest of the world goes about its business. The American poet William Carlos Williams (1883–1963) wrote the following poem about Pieter Brueghel's Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, (1555):

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

near

the edge of the sea

concerned

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings' wax

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

What happens to the language when the Chorus starts to talk about Faustus's study of magic? In the two lines ‘And glutted more with learning's golden gifts, / He surfeits upon cursèd necromancy’ (ll. 24–5), ‘glutted’ means ‘overfull’, or ‘stuffed’, and ‘surfeits’ means ‘to eat too much’, ‘to gorge oneself’. Why is the Chorus referring to eating, specifically to eating too much? It seems that once again the language is not working literally; instead, it is drawing metaphorical links between Faustus's intellectual curiosity and a kind of greedy self-indulgence. He is portrayed as a glutton who, stuffed full of ‘learning's golden gifts’, turns to magic and gorges himself on that as well.

So, by looking closely at the language of the Prologue, we can see more clearly what the Chorus is saying about Faustus – that it associates his intellectual ambition with an immoderate appetite, with an inflated sense of his own value, and with a dangerous, Icarus-like overreaching that brings him into conflict with the Christian God. So even though the Prologue praises Faustus for his intellectual brilliance, it also insists that this brilliance is not an unqualified good; if it pushes past certain boundaries, it becomes sinful and provokes divine punishment. The Prologue tells us, in short, that the play's protagonist lives in a Christian universe that places limits on the pursuit of knowledge.

2.1.2 Faustus's first speech

The Chorus now introduces Faustus, who delivers his first speech of the play. The way the speech is staged and written serves to emphasise Faustus's position as an eminent scholar. It is set in his study, and he is surrounded by books, from which he reads in Latin. The works he consults, written by such great thinkers of classical antiquity as the Greek philosopher Aristotle, the Greek medical authority Galen, and the Roman emperor Justinian, were central texts in the sixteenth-century university curriculum. The first impression the speech gives us, then, is of the breadth of Faustus's learning.

There is no one on stage with Faustus as he delivers these lines, which means that it is a soliloquy, a speech in which a dramatic character, alone on stage, expresses his or her thoughts, feelings and motives. The soliloquy is an ideal device for establishing a strong relationship between a character and an audience, for it seems to give us access to that character's mind at work. In Faustus's opening soliloquy, we notice right away that he is addressing himself in the third person – ‘Settle thy studies, Faustus, and begin’ (l. 1) – which creates the impression that he is talking to himself. We listen as he tries to make up his mind, now that he has been awarded a doctorate in theology, what subject he wants to specialise in. He declares that he will be a ‘divine’ only in appearance (‘in show’), while aiming to achieve expertise in every academic discipline. Immediately, then, we hear a note of dissatisfaction and restlessness in Faustus's voice; despite his dazzling academic success, he is impatient for more knowledge.

Yet as he runs through the four main academic disciplines he has studied – philosophy, medicine, law and theology – he dismisses each of them as an intellectual dead-end. Faustus feels that he has already achieved everything that the study of philosophy and medicine has to offer. He then rejects the law as suitable only for a ‘mercenary drudge’ (l. 34). For a moment, he returns to divinity as the most worthy profession, but then rejects that as well, as the passages he reads from Jerome's Bible stress only human sinfulness and the damnation that awaits it.

So what is it that Faustus wants that these traditional fields of study fail to supply? When contemplating his own remarkable achievements in medicine, he laments that although he can cure illness, he is unable either to give his patients eternal life or to raise them from the dead: ‘Yet art thou still but Faustus, and a man’ (l. 23). What he wants, then, is to transcend his human limitations, to break through the boundaries that place what he sees as artificial restrictions on human potential. He has gone as far as his human condition will allow him to go, but wants to go further still, which means transforming himself into a ‘mighty god’, ‘a deity’ (ll. 64, 65), a goal he feels only magic will enable him to realise.

When Faustus declares that he wants to achieve something that ‘[s]tretcheth as far as doth the mind of man’ (l. 63), he expresses an intense optimism about human ability that has often been seen as characteristic of the Renaissance, and as the quality that most distinguishes it from the more religious Middle Ages. Historical periods are too complex to be boiled down to a single, defining essence; nor are there clear breaks between them. Nevertheless, there were developments in Europe from the fourteenth to the eighteenth century that, broadly speaking, encouraged a newly secular view of the world: the growth of scientific investigation into the structure of the universe and the laws of the physical world; the voyages of exploration, expansion of trade routes and colonisation of the Americas; the new technology of printing, which allowed for the rapid dissemination of new ideas and discoveries; and the development of a humanist educational programme, based on the study of ancient Greek and Latin authors, and dedicated to the restoration of classical ideals of civic virtue and public service. When Faustus fantasises that ‘All things that move between the quiet poles / Shall be at my command’ (ll. 58–9), his speech is inflected with the scientist's and coloniser's desire for control over the natural world (Hopkins, 2000, p. 62). When he tells Mephistopheles that he is not afraid of damnation because he believes instead in the classical Greek afterlife (see 1.3.60–1), he voices a humanist reverence for classical culture.

It is highly unlikely, though, that any sixteenth-century humanist would have countenanced this kind of explicit challenge to Christian doctrine, so if Faustus represents the secular aspirations of the Renaissance, he does so in an extreme or exaggerated form. Moreover, the fact that Doctor Faustus is set in a Christian universe and affirms the reality of hell and damnation should warn us not to overstate the secular values of Renaissance England. Indeed, what the play explores – its principal theme – is the conflict between the confidence and ambition its protagonist embodies, and the Christian faith, which remained a powerful cultural force when Marlowe was writing and required humility and submission to God's will. The play's two opening speeches set up an opposition between the Prologue's view of boundless ambition as sinful presumption and Faustus's implicit claim that the Christian universe places unjust restrictions on human potential.

Which side in this conflict do you think the play encourages us to take? We saw earlier that the Prologue seeks to discredit Faustus's interest in necromancy by portraying it in terms of an intemperate appetite. Is there more evidence in the opening scene to support its claim?

Activity

Have another look at Faustus's speech on page 4, lines 80–101, in which he imagines the power that magic will bring him. What is it he wants to achieve with this power? What kinds of motives or desires do you think he expresses in these lines?

Discussion

The Good and Evil Angels have just made their first appearance, and in response to the Evil Angel's promise that magic will allow him to be ‘on earth as Jove is in the sky’ (l. 78), Faustus exclaims ‘How am I glutted with conceit of this!’ (l. 80). Right away, then, he echoes the language of the Prologue and so identifies his own longing for godlike power with a gluttonous craving. A few lines later he thinks of the gold and precious jewels the magical spirits will bring him, along with ‘pleasant fruits and princely delicates’, or delicacies (l. 87). You may have noticed as well how often Faustus repeats the phrase ‘I'll have’, which makes him sound like a greedy child in a sweet shop. Yet alongside these acquisitive and hedonistic impulses he expresses a genuine thirst for knowledge, for example, when he says he wants the spirits to ‘resolve’ him ‘of all ambiguities’, or to answer all his questions (l. 82), and to read him ‘strange philosophy’ (l. 88). His desire to overturn the university dress code by filling the universities with silk ‘Wherewith the students shall be bravely clad’ (l. 93) strikes me as a harmless, even appealing, expression of social rebellion.

Faustus's motives in this speech seem to be mixed, neither all good nor all bad, rather like the Chorus's initial portrait of him. I'd like to say a bit more at this point about Faustus's desire to levy soldiers to ‘chase the Prince of Parma from our land’ (l. 95). In this line he is voicing antipathy to an Elizabethan hate-figure. Doctor Faustus was written during a protracted period of military conflict with Catholic Spain. The Prince of Parma was the Spanish governor of the Netherlands, and in the 1580s he was closely involved both in Spain's plans to invade England and in the suppression of a Protestant rebellion in the Netherlands which England supported. It's true that the pro-Protestant force of Faustus's statement is somewhat weakened by the fact that he seems to want rid of the Prince of Parma so that he himself might ‘reign sole king of all our provinces’ (l. 96); still, the play's original audience is likely to have warmed to the picture of this representative of Spanish Catholic military might being ignominiously chased out of northern Europe.

This is a good example of the way in which reading literary texts with their historical context in mind can help to shed light on their meaning. The mention of the Prince of Parma in this speech strongly suggests that Marlowe was, at least to some extent, seeking to arouse audience support for Faustus.

2.1.3 The comic scenes

There is no doubt though that the play keeps drawing our attention to its protagonist's weaknesses. The comic scenes in Act 1 serve to reinforce the connection between magic and appetite. In Act 1, Scene 4, Wagner tells us that Robin is so poor that ‘he would give his soul to the devil for a shoulder of mutton, though it were blood raw’ (ll. 9–11) and Robin adds: ‘Not so, good friend. By'r Lady, I had need have it well roasted, and good sauce to it, if I pay so dear’ (ll. 12–15). Coming directly after the scene in which Faustus first conjures Mephistopheles, the joke glances at Faustus's own ‘hunger’ and drives home the absurdly high price he is paying for comparatively trivial pleasures. This is one of the main functions of the play's comic scenes – to comment on the serious action. Time and again, Marlowe juxtaposes scenes so that the later comic one comments on the preceding serious one by re-presenting Faustus's ambitions in their lowest form, stripped of the power of his own speeches. By techniques such as these the play diminishes its hero by exposing the triviality and foolishness of his aims.

2.2 Act 2, Scene 1: Faustus and God

By the end of Act 1, Faustus appears to have made up his mind to sell his soul to the devil in exchange for twenty-four years in which he will ‘live in all voluptuousness’ (1.3.94). Act 2, Scene 1 opens with another soliloquy.

Activity

Please look now at this soliloquy (page 15, lines 1–14). How would you describe its mood? Jot down any points you think are important about the way the language helps to create this mood.

Discussion

I would say that the mood of this speech is one of self-doubt and inner division. Just as in the first soliloquy, Faustus is talking to himself, but on this occasion the voice we hear sounds markedly less confident. One possible reason for this is that the speech is peppered with questions which seem to betray his uncertainty about his chosen course of action; for example, in line 3 he asks himself, ‘What boots it [what use is it] then to think of God or heaven?’. The question is followed by a series of commands: ‘Away with such vain fancies and despair! / Despair in God and trust in Beelzebub. / Now go not backward. No, Faustus, be resolute’ (ll. 4–6). Faustus is ordering himself not to backtrack, but to no avail, as his next question makes clear: ‘Why waverest thou?’ (l. 7). Suddenly another voice appears, urging repentance: ‘Abjure this magic and turn to God again!’ (l. 8). This voice seems to get the upper hand briefly, but Faustus silences it with an extreme statement of his commitment to the devil.

Faustus appears to be wrestling with his conscience in this soliloquy. He clearly feels the urge to repent, so why doesn't he? It is interesting that although he delivers this speech before he has signed his contract with Lucifer, he tells himself in the first line that he must ‘needs be damned’; in other words, he sees his own damnation as unavoidable. So what's the point, he asks himself, of thinking of God or heaven? The repetition of the word ‘despair’ in lines 4 and 5 emphasises Faustus's hopeless state of mind. If you count the syllables in lines 2 and 10, you will see that each line has only six. This means that in performance the actor would have to pause for a moment because the lines are shorter than normal, and this would have the effect of drawing attention to the sentiments expressed in the two lines, that is, to Faustus's despairing conviction that he cannot be saved and that God does not love him.

Why should Faustus feel so strongly that he is damned, when at this point in the play there seems to be every reason to believe that repentance will secure God's forgiveness? Some critics, most notably Alan Sinfield (1983) and John Stachniewski (1991), have argued that Marlowe is exploring the mental and emotional impact of the form of Protestantism that prevailed in England during the late sixteenth century, based on the doctrines of the French-born Protestant reformer Jean Calvin. Calvinist theology developed and changed over time, but at this historical juncture it stressed the sinfulness and depravity of human nature. In contrast to the traditional view of salvation as something that an individual could earn by living a virtuous Christian life, Calvinism argued that salvation is entirely God's gift rather than the result of any human effort. Moreover, according to the doctrine of predestination, God gives that gift only to a fortunate few whom he has chosen; everyone else faces an eternity of hellfire.

This theology formed the official doctrine of the Elizabethan Church. However bleak it sounds, its effect on believers was often positive; for those persuaded by their own virtuous impulses that they were chosen by God, it proved an enormous source of comfort and well-being, perhaps especially for poorer members of society, for whom the conviction of divine favour could be empowering. But for some, these doctrines provoked a sense of powerlessness and anxious fear about their spiritual destiny. It is possible to argue that Marlowe's Faustus is a depiction of one of these casualties of Calvinist doctrine, and that this helps to explain not only his opening dismissal of Christianity as obsessed with sin and damnation, but his repeated inability to repent. As in the soliloquy that opens Act 2, he cannot bring himself to believe that God favours him and has granted him salvation. The desire for repentance is overwhelmed by a still stronger belief, consistent with Calvinist doctrine in its early modern form, that the chances are that God does not love him at all.

However, it isn't necessary to believe that Doctor Faustus is specifically about Calvinism to feel that its portrait of the Christian God who vindictively ‘conspires’ Faustus's overthrow is not entirely flattering. Numerous critics have been troubled by a particular episode in the play that seems to cast doubt on the presence of divine mercy and benevolence. This is the moment in Act 2, Scene 3 when Faustus makes his most serious attempt at repentance. He quarrels with Mephistopheles, the Good Angel (unusually) gets the last word in the debate with the Evil Angel, and Faustus calls out to Christ ‘to save distressèd Faustus’ soul’ (2.3.85). And what happens? Lucifer, Beelzebub and Mephistopheles enter. Why does God not intervene to save Faustus? The stony silence that greets his plea for divine assistance seems to call into question the traditional Christian notion of a loving and merciful God.

Other critics have argued that God is silent on this occasion because Faustus's repentance is insincere, and that he consistently fails to repent not because he is suffering from theologically-induced despair, but because he is afraid of the devils and constantly distracted by the frivolous entertainments they stage for him, like the pageant of the seven deadly sins which follows this episode. One could argue as well that the play does represent the Christian God as loving and merciful, and shows human beings to be free to shape their own spiritual destinies. The Good and Evil Angels, after all, seem to give dramatic form to Faustus's freedom to choose: he has a choice between good and evil, and he chooses evil in full knowledge of what the consequences will be. As late as Act 5, Scene 1, the Old Man appears on stage to drive home the availability of God's mercy if only Faustus will sincerely repent his sins. Looked at from this perspective, it is Faustus and not God who is responsible for the terrible fate that greets him at the close of the play.

This critical debate serves to remind us that it is difficult to evaluate how much sympathy the play arouses for its protagonist without taking into consideration its treatment of the Christian God. If you think the God of the play is fundamentally benevolent then you are less likely to feel favourably disposed towards Faustus than if you think he comes across as a harsh and punitive cosmic despot. It is clear, though, that the play offers textual evidence in support of both views. Once again, we find Marlowe refusing to be pinned down to one interpretation.

2.3 Acts 3 and 4: What does Faustus achieve?

Act 2 points repeatedly to the failure of Faustus's attempt to secure power and autonomy through his pact with Lucifer: in Act 2, Scene 1 Mephistopheles declines his request for a wife, and in Act 2, Scene 3 he refuses to tell him who made the world. Acts 3 and 4 cover the bulk of the twenty-four-year period that Faustus purchased with his soul. How do they make us feel about what he actually achieves through his embracing of black magic? Are we encouraged to feel it was worth it?

Activity

Please have another look at Act 4, Scenes 1 and 2 (pages 35–43). On the basis of these scenes, would you say that Faustus has realised his dreams of power and pleasure? What evidence would you offer in support of your view?

Discussion

These two scenes show us Faustus in the role of court magician, entertaining the emperor Charles V and then the Duke and Duchess of Vanholt with conjuring tricks. Many critics have felt that these scenes highlight the hollowness of Faustus's achievements; far from realising his grand dreams of immense power, all he manages to become is the entertainer of the established ruling elite. Marlowe certainly makes a point in Act 4, Scene 1 of stressing the limitations of his protagonist's conjuring powers. Because Faustus is still unable to raise people from the dead, he can do no more than summon spirits who resemble Alexander and his paramour. In Act 4, Scene 2 the point seems to be not that Faustus lacks the power to fulfil the request made of him by his aristocratic employer, but that the Duchess of Vanholt can think of nothing more challenging to ask for than a dish of ripe grapes, to which Faustus replies, apparently with some regret, ‘Alas, madam, that's nothing’ (4.2.14). He seems at this point to share the view of many critics that he is squandering his abilities on trivial activities.

Yet is this all there is to say on this matter? As usual with this play, there is another side to the story, especially if we consider Act 3. Earlier we looked at Faustus's desire to ‘chase the Prince of Parma from our land’, and speculated how, in a climate of military conflict with Spain, it might have endeared him to the play's original audience. At the time of the play's first performances, the Catholic Church would have been viewed by many with comparable hostility. In 1570 the Pope had excommunicated Elizabeth I and released her Catholic subjects from their allegiance to the Protestant heretic queen; in 1580 he proclaimed that her assassination would not be a mortal sin. Read with this context in mind, Act 3, Scene 1, in which Faustus makes a fool of the Pope under cover of his magician's cloak of invisibility, looks like a bid for audience approval, by its portrayal of the Catholic Church as decadent and corrupt, and mired in absurd superstitions like the ceremony of excommunication. By casting Faustus in the role of Protestant hero, this scene seems designed to elicit a favourable response to his conjuring skill.

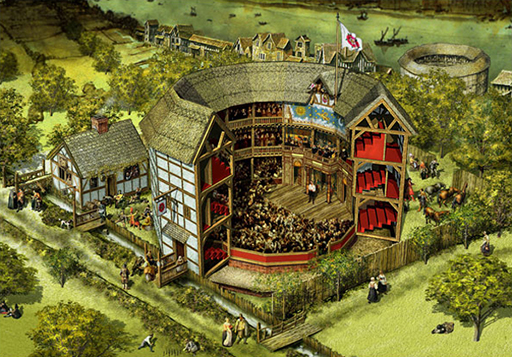

We need to remember as well the limitations of the theatre, in particular of Marlowe's open-air theatre, where plays were performed in broad daylight with little in the way of props, scenery or artificial lighting see Figure 4). In these conditions, it is not hard to grasp why so many of Faustus's adventures as a magician are reported rather than enacted: the Chorus to Act 3, for example, tells us that in order to learn ‘the secrets of astronomy’ (3.1.2), Faustus scaled Mount Olympus ‘in a chariot burning bright / Drawn by the strength of yoky dragons' necks’ (3.1.5–6). This sounds anything but a hollow experience, and when discussing Acts 3 and 4 we should give due weight to the descriptions Marlowe provides of activities he was unable to enact on stage, especially given that these descriptions probably had a powerful impact on the play's original audience, who were much more accustomed to listening to long and often complex speeches (sermons, for example) than we tend to be nowadays.

The mention of the play in performance leads us to an important characteristic of drama, which makes it different from other literary forms such as the novel and poetry: plays are written to be performed whereas novels and poems are written to be read. This means that a play is not so much a fixed and finished literary text as a blueprint for actors and directors who will have to make decisions about how it is going to be translated from the page to the stage. They will have to ask themselves questions, such as what is actually happening on stage at any given moment? How should a particular speech be spoken by the actor playing the part, and which actor is best suited to play the part? A director will also need to make decisions about set design, costumes, lighting, music and other sound effects. All of these aspects of performance will contribute to the meaning of the play, and they will differ from one production to another.

Activity

So how might consideration of Doctor Faustus as a text intended for performance affect our response to Faustus's career as a magician? A moment ago we discussed the way in which Act 4 in particular seems to emphasise the gap between Faustus's aspirations and his actual achievement. Does thinking about these scenes in terms of performance open up different possibilities?

Discussion

It strikes me that Act 4, Scene 1, for example, in which Faustus conjures up the image of Alexander the Great and his paramour, could easily, with the skilful use of music and lighting, be turned into a thrilling stage spectacle. It might then be possible to perform Act 4 in such a way as to create the impression not of the emptiness, but of the wonder of Faustus's magical powers.

The same might be said of the two appearances of Helen of Troy in Act 5, Scene 1. This scene is structured in such a way as to establish a clear contrast between Faustus's two encounters: with the Old Man, who urges piety and repentance, and with the legendary beauty Helen of Troy (Figure 5). Faustus chooses Helen, and many critics have echoed the Old Man's stern disapproval. Yet the critic Thomas Healy points out that in the theatre Helen is usually represented as so ‘strikingly beautiful’ that even if one agrees on a rational level that Faustus would be better off with the Old Man, on a visual level the Old Man loses out to Helen, who engages what Healy calls the audience's ‘emotional and aesthetic sympathy’ (Healy, 2004, p. 183). By the same token, a director might choose to portray Helen instead as a malign influence on the hero.

2.4 Act 5, Scene 2: Faustus's last soliloquy

The play draws to a close with Faustus's final soliloquy, which is supposed to mark the last hour of his life.

Activity

Please reread this speech now, thinking as you read about how Marlowe uses sound effects to heighten the emotional impact of the soliloquy.

Discussion

The soliloquy represents an attempt to imagine and dramatise what the last hour of life feels like to a man awaiting certain damnation. Of course, the speech doesn't really take an hour to deliver, but Marlowe uses the sound of the clock striking to create the illusion that the last hour of Faustus's life is ticking away and so heightens the sense of impending doom. It strikes eleven at the start of the speech, then half past the hour 31 lines later, then midnight only twenty lines after that. Why does the second half hour pass much more quickly than the first? Is this Marlowe's way of conveying what the passage of time feels like to the terrified Faustus: it seems to be speeding up as the dreaded end approaches? The thunder and lightning that swiftly follow the sound of the clock striking midnight announce the final entrance of the devils.

Critics have often commented on how skilfully Marlowe uses rhythm to underline the passage of time. Look, for example, at the second line: ‘Now hast thou but one bare hour to live’ (l. 67). Because this is a sequence of monosyllabic words, it is not entirely clear which of them are stressed. It would certainly be possible for an actor to give a more or less equally strong stress to each word, which is why O'Connor points out that the line seems to echo the striking clock we have just heard (p. 108). This echo effect is strengthened by the internal rhyme between ‘Now’ and ‘thou’. The monosyllabic words continue into the next line until the last word: ‘And then thou must be damned perpetually’ (l. 68). The sudden appearance of a long five-syllable word focuses our attention on it and alerts us to what it is that Faustus most fears: an infinity of suffering. This sparks his desperate and futile plea for time to stand still, and Marlowe underlines the futility through the use of enjambement, or run-on lines:

Fair nature's eye, rise, rise again, and make

Perpetual day; or let this hour be but

A year, a month, a week, a natural day … (ll. 71–3)

Faustus wants time to stop or slow down, but the way one line of verse tumbles into the next, accelerating rather than slowing down the rhythm, seems to signal the inevitable frustration of that wish. Faustus himself grasps this: ‘The stars move still; time runs; the clock will strike; / The devil will come, and Faustus must be damned’ (ll. 76–7).

Time really is the essence of this soliloquy, not only because the clock is ticking for Faustus, but because, as we have seen, what most horrifies him is the prospect not of suffering but of endless suffering. After the clock strikes the half hour, Faustus pleads with God to place a limit on his time in hell – ‘Let Faustus live in hell a thousand years, / A hundred thousand, and at last be saved’ (ll. 103–04) – only to come back to the awful truth: ‘O, no end is limited to damnèd souls’ (l. 105).

One of the most striking aspects of the speech is the way it reverses the dreams of power and glory that Faustus expressed in his first soliloquy. In that speech he declared his desire to be more than human, to be a ‘mighty god’, but now, as he faces an eternity in hell, he wishes that he were less than human: he longs to be transformed into ‘some brutish beast’ whose soul would simply dissolve into the elements when it dies (ll. 109–12), or that his soul might ‘be changed into little waterdrops, / And fall into the ocean, ne'er be found’ (ll. 119–20). In his final soliloquy, Faustus's self-assertive spirit collapses into a desire for extinction; his aspiration to divinity into a longing for annihilation as he seeks desperately to escape from ‘the heavy wrath of God’ (l. 86).

Does this final humbling of Faustus encourage a feeling of satisfaction that he has got what he deserved? That seems to be how the Epilogue sees things. As in the Prologue, the Chorus begins by acknowledging Faustus's greatness, but in essence it is issuing a warning to the audience that his terrible fate is what awaits all those ‘forward wits’ who ‘practise more than heavenly power permits’ (ll. 7–8). Yet it is arguable that the final soliloquy's powerful evocation of Faustus's agony, coupled with its stress on the horrors of the never-ending suffering to which he has been sentenced, are designed to make us wonder whether the savage punishment really fits the crime. Feelings of pity and fear might seem a more appropriate response to Faustus's end than the Epilogue's moral, as tidy as its concluding rhyming couplet.

2.5 Morality play or tragedy?

Pity and fear are the emotions that, according to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, are aroused by the experience of watching a tragedy. At the start of this chapter we asked whether Doctor Faustus is a late sixteenth-century morality play, designed to teach its audience about the spiritual dangers of excessive learning and ambition. When the play was published, first in 1604 and then in 1616, it was called a ‘tragical history’; if we take ‘history’ here to refer not to a particular dramatic genre but more generally to a narrative or story, then the publisher described the play as a tragic tale. So what is a tragedy? In fact, ‘tragedy’ is a notoriously difficult literary term to define, for it seems to take various forms in different historical periods. But for the sake of discussion, we can fall back on the broad strokes of Aristotle's description (in the Poetics) of the tragedies he had seen in Athens in the fourth century BCE: tragedies are plays that represent a central action or plot that is serious and significant. They involve a socially prominent main character who is neither evil nor morally perfect, who moves from a state of happiness to a state of misery because of some frailty or error of judgement: this is the tragic hero, the remarkable individual whose fall stimulates in the spectator intense feelings of pity and fear.

To what extent does Doctor Faustus conform to this description of a tragic play? Well, it follows the classic tragic trajectory in so far as it starts out with the protagonist at the pinnacle of his achievement and ends with his fall into misery, death and (in this case) damnation. From the beginning the play identifies its protagonist not as ‘everyman’, the morality play hero who ‘stands for’ all of us, but as the exceptional protagonist of tragic drama. Moreover, it is certainly possible to argue that Faustus brings about his own demise through his catastrophically ill-advised decision to embrace black magic. Perhaps most importantly, we have seen in the course of this course that Faustus is consistently presented to us as an intermediate character, neither wholly good nor wholly bad: both brilliant and arrogant, learned and foolish, consumed with intellectual curiosity and possessed of insatiable appetites for worldly pleasure, a conscience-stricken rebel against divine power. We have seen as well how skilfully Marlowe uses the soliloquy to create a powerful illusion of a complex inner life: from Faustus's first proud rejection of the university curriculum and his exuberant daydreams of unlimited power, to his anguished self-questioning and final terrified confrontation with the divine authority he defied, the play gives us access to the thoughts and feelings of a dramatic character whose fall, whether or not we feel it is deserved, seems to call for a fuller emotional response than the Epilogue's moralising can provide.

3 Hero and author

What, if anything, does Doctor Faustus tell us about its notorious author? Having read the play, do you feel that it supports or invalidates the dominant view of Marlowe as the bad boy of Elizabethan drama? There is certainly no doubt that the play has a defiant streak, that it calls into question the justice of a universe that places restrictions on human achievement and demands the eternal suffering of those who disobey its laws. On this level, it does seem to be the work of an author disinclined to take orthodox beliefs on trust, who bears some resemblance to the restless, irreverent personality described and decried by the likes of Baines and Beard. However, we have seen throughout this course that this allegedly rebellious figure produced a play that, if it questions divine justice, also insists on the egoism and sheer wrong-headedness of its erring protagonist, and powerfully conveys his feelings of guilt and remorse. Perhaps the play's ambiguity is a measure of how risky it would have been for Marlowe to write a more overtly subversive drama; yet one could also argue that the play's orthodox sentiments are too deeply felt to be dismissed as camouflage for the author's heretical opinions. In the end, all we can say is that Marlowe's treatment of the Faust legend is neither simply orthodox nor simply radical. With its stubborn resistance to single, fixed meanings, Doctor Faustus leaves the character and beliefs of its author in shadow. Yet if we cannot finally assess the accuracy of Marlowe's reputation as a rebel and outsider, I hope that your reading of the play has made clear why he also has a reputation as a pioneer of English drama.

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying the arts and humanities. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Dr Anita Pacheco.

This free course is adapted from a former Open University course called The Arts Past and Present (AA100). You might be interested in a more recent Open University course, A111 Discovering the arts and humanities.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Wellcome Images in Wikimedia made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

The content acknowledged below is Proprietary and is used under licence.

William Carlos Williams, ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’, from Collected Poems, II: 1939-1962. © by William Carlos Williams. Used by permission from Carcarnet Press Limited and New Directions Publishing Corp.

Figure 1 The Corpus Christi Portrait, thought by some to be of Christopher Marlowe, The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Used courtesy of The Masters and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

Figure 2 ‘Fall of Icarus’ from Geffrey Whitney’s ‘Choice of Emblemes’, 1586. Stirling Maxwell Collection, Glasgow University Library, SP coll. S.M.1667. Used with permission of Special Collections of the University of Glasgow Library.

Figure 3 Pieter Brueghel, ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’, 1555, transferred from panel. Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels. Photo: © 1990, Scala, Florence.

Figure 4 William Dudley, ‘The 1587 Rose Theatre: A Cutaway View’, 1999 for the onsite exhibition which was also designed by Dudley. Used with permission, http://bill-d.cgsociety.org/gallery/.

Figure 5 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ‘Helen of Troy’, 1863, oil on panel, 33 x 28cm. Photo: Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg/ Bridgeman Art Library

Figure 6 Title Page of the 1620 edition of the ‘B’ text of Doctor Faustus, first published in 1616: ‘The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus’, The British Library, London. C. 1891-6 c.39.c.26. © The British Library. All rights reserved.

The Corpus Christi Portrait, thought by some to be of Christopher Marlowe, The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Used courtesy of The Masters and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University