Week 4: Debt and borrowing

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 25 May 2024, 2:15 PM

Week 4: Debt and borrowing

Introduction

The UK’s mountain of personal debt. Are there ‘good’ and ‘bad’ debts? How the Bank of England sets interest rates. Interest calculations – simple and compound. How does inflation affect the cost of borrowing?

Martin welcomes you back to tackle debt, interest and inflation.

Transcript

This course is presented with the kind support of True Potential LLP.

The True Potential Centre for the Public Understanding of Finance (True Potential PUFin) is a pioneering Centre of Excellence for research in the development of personal financial capabilities. The establishment and activities of True Potential PUFin have been made possible thanks to the generous support of True Potential LLP, which has committed to a five-year programme of financial support for the Centre totalling £1.4 million.

4.1 Personal debt

In the video Martin Lewis – money saving expert and media adviser on financial management – engages in a discussion with an audience about good and bad debt.

Transcript

Debt is a topical issue, and for many households a sensitive and problematic one. But it’s necessary to take a measured approach and recognise, as Martin Lewis demonstrates, that all debts are not bad debts.

Debt arises when we borrow money, and there are many forms of borrowing – from credit card debt to bank overdrafts, bank loans, student loans (to finance higher education) and mortgages (to finance the purchase of property or land). Debt can be used to provide finance for everything from day-to-day spending (you’ll be aware of the growth in recent years of ‘payday’ loans) to holidays and to items we use over a number of years, such as furniture, cars and our homes.

Since 1993 the aggregate (total) value of personal debt has risen 3.5 times to a total of £1.56 trillion. The vast majority – around 87% – of this is ‘secured debt’, money lent against the security of property or other assets that the lenders can take possession of if the borrower fails to repay the money that has been lent to them. The rest is unsecured debt, which since the late 2000s has actually fallen slightly in aggregate value.

The UK has seen some dramatic swings in interest rates in recent decades – from the highs of the early 1980s to the historic lows we’re currently witnessing. So getting to grips with the factors that determine how much we have to pay on our debts is an essential aspect of financial planning.

4.1.1 Debt and interest – some basics

When someone acquires a debt, the money they have to repay to the lender consists of three elements.

First, there’s the amount originally borrowed – this is normally referred to as the principal sum, or sometimes the capital sum. Let’s say £10,000 is borrowed for five years to buy a car, how will this be repaid? There are two usual ways in which this principal sum can be repaid: either in one amount at the end of the term of the loan (in this case, five years), or in stages over the life of the loan. The former is often referred to as an ‘interest-only loan’ and the latter a ‘repayment loan’. If the principal sum is to be paid off in full at the end of the loan period, the borrower will need to have the money available through building up other savings to pay off the loan. An example of this type of loan is an endowment mortgage, which used to be a common way of buying a home – an interest-only loan is combined with saving through an endowment insurance policy that hopefully builds up enough lump sum to pay off the loan at the end of its term.

Second, there’s the important additional cost of having debt: the interest that has to be paid on it. In effect, interest is an additional charge on the repayment of debt. It is normally expressed as a percentage per year – for example 7% per annum, more commonly abbreviated to 7% p.a. The charging or paying of interest is generally rejected by sharia law, as it used to be by some Christians in earlier centuries. In modern economies the concept of interest comes about because lenders require recompense for three factors: for the access to the money they have given up; for the risk associated with not getting their money back; and to cover the expected inflation rate over the coming year.

Third, there may be charges associated with taking out, having or repaying debt. These will be explored in more detail later.

4.1.2 More on interest

Let’s look at interest payments in more detail. If £10,000 is borrowed and no repayments of this principal sum are made during the year, and the interest rate is 7% p.a. with interest being paid once a year at the end of the year, the interest charge for that year is £700.

So, provided the principal sum owed to the lender remains at £10,000 and the interest rate is 7% p.a., the borrower will have to pay £700 each year to the lender. This is an example of a simple interest calculation where the interest rate is applied just to the original sum borrowed.

If you want to look further into the cost of borrowing and the interest you pay on a loan, you can practice using the MAS loan calculator.

4.1.3 How much interest?

This quiz allows you to test your ability to calculate interest.

Activity 1

a.

£5000

b.

£2500

c.

£17,500

d.

£3350

The correct answer is b.

a.

£3750

b.

£46,650

c.

£44,890

d.

£3350

The correct answer is d.

4.1.4 Compounding of interest

As you completed the calculations in the quiz, you may have started to think of some factors that could complicate the calculation of the interest charge. For example, what would be the interest charge if some of the principal sum is repaid during the course of the year?

In many cases, the answer is that the interest rate calculation will be based on the average balance of the principal sum during the year. For instance, if £10,000 is owed at the start of the year and £100 is repaid halfway through each month, then the outstanding balance at the end of the year would be £8800. The average balance of principal outstanding during the year would be the average (mean) of the balance at the start and at the end of the year, or £9400 = ((£10,000 + £8800)/2). Based on this average balance, the interest for the year at 7% p.a. would be £658 = (£9400 x 7/100) – rather less than the £700 if no repayment of the principal sum had been made.

What happens if the borrower does not repay the interest due to the lender? Again, this will depend on the details of the contract with the lender and their attitude to borrowers who fall into arrears. Normally, the lender will add the interest charge left unpaid to the principal sum. This means that the following period’s interest charge is going to be higher since the borrower will be paying interest, not only on the original principal sum but also on the unpaid interest. This is known as compounding, and can quickly enlarge debts.

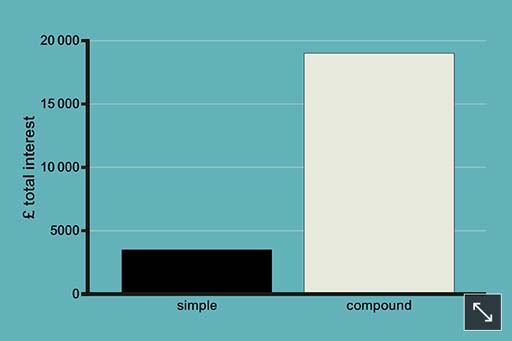

The example of compounding that you see in Figure 3 illustrates what happens if someone borrows £1000 at an interest rate of 35% and makes no repayments over ten years. Over this period of time, the debt would rise from £1000 to £20,107 (£19,107 interest on top of the £1000 borrowed). This is much more than if interest had been charged on a simple rather than compound basis – simple interest over ten years would have been just £3500.

The dangers of compounding were demonstrated vividly in a famous case which came to court in the UK in 2004. A debt of £5750 grew to the staggering sum of £384,000 in 15 years. In the event, the debt was (unusually) cancelled for being ‘extortionate’. Yet it showed the risks of compounding very clearly.

The precise practice for computing the interest charge varies among different lenders – and interest can be calculated by different lenders at different time intervals. One of the pieces of financial small print it is always vital to read is the basis on which interest is charged – that is, how often and by reference to what terms. For instance, if a person is repaying some of the principal sum of their loan regularly, the interest charged will be lower if the interest charge is calculated on a daily basis, rather than on a monthly or an annual basis. (Interest charged on an annual basis will be the least favourable option if repayments of the principal sum are being made.)

4.1.5 What determines the level of interest rates?

To understand what determines the level of interest rates charged when you borrow money, you first need to understand how ‘official’ interest rates are set.

The video, which features Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, sets the scene by looking at the factors taken into consideration when setting official interest rates.

Transcript

Prior to 1997, ‘official’ interest rates in the UK were determined by the UK government, usually after consultation with the Bank of England. Arrangements changed in May 1997 when the incoming Labour government passed responsibility for monetary policy and the setting of interest rates to the Bank of England to make the bank independent of political influence. This matches the arrangement in the USA and in the ‘euro zone’, where the Federal Reserve Bank and the European Central Bank respectively set official rates.

The rate set by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) known as the ‘Bank Rate’ is the rate at which the Bank of England will lend to the financial institutions. This, in turn, determines the level of bank ‘base rates’ – the minimum level at which the banks will normally lend money. Consequently, Bank Rate (also known as the ‘official rate’) effectively sets the general level of interest rates for the economy as a whole.

Note, though, that for individuals the rate paid on debt products will be at a margin – sometimes a very high margin – over Bank Rate and bank base rates. Indeed, one of the consequences of the financial crisis was that the margin between Bank Rate and the rate paid on debts widened sharply (except for those products whose rate was contractually linked to the Bank Rate).

Each month, the Bank of England’s MPC meets for two days to consider policy in the light of economic conditions – particularly the prospects for inflation. The MPC’s decision is announced each month at 12 noon on the Thursday after the first Monday in the month.

The prime objective is for the MPC to set interest rates at a level consistent with inflation of 2% p.a. For example, if the MPC believes inflation will go above 2% p.a. it might increase interest rates in order to discourage people from taking on debt – because if people spend less, it could reduce the upward pressure on prices. Conversely, if the MPC believes inflation will be much below 2% p.a. it might lower interest rates (also known as ‘easing monetary policy’) – people might then borrow and spend more.

However, in 2013 and 2014 the policy on the setting of official rates was modified to take greater account of the level of unemployment in the economy. First it was announced that official rates would not be raised while the rate of unemployment was above 7% of the labour force. Subsequently, following a sharp fall in unemployment towards and then below 7%, this stance was modified to one where the MPC would take account of the extent of spare capacity in the economy rather than just the rate of unemployment. The video explores this change of emphasis to the setting of official interest rates in the UK.

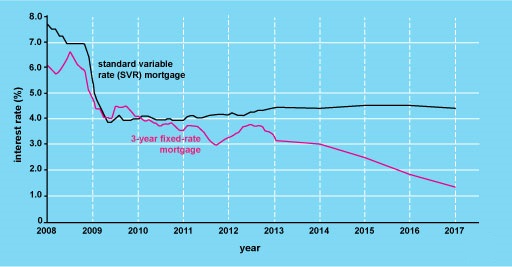

Official rates of interest tend to be cyclical, rising to peaks and then falling to troughs. Since 1989 the trend in the UK has been for nominal interest rates to peak at successively lower levels. Nominal rates fell to 3.5% in 2003. In 2009 they hit a record low of 0.5% and were still at this level in May 2016. This is because the Bank of England has been attempting to stimulate economic activity following the period of recession at the end of the 2000s. However, the benefit of these low nominal interest rates was not fully experienced by borrowers as the margin widened between the Bank of England’s Bank Rate and the rate charged by lenders on many of their debt products.

In November 2017 Bank Rate was raised for the first time in 10 years – from 0.25% to 0.5%. The change, although modest, was taken as a signal that future years will see higher interest rates than those experienced since the financial crisis of 2007/08.

4.1.6 Real interest rates

You will recall from Week 2 that it is important to take inflation into account when managing your finances. In Week 2 you looked at the distinction between nominal and real income, the latter taking into account the level of price inflation. Now you do the same in looking at interest rates.

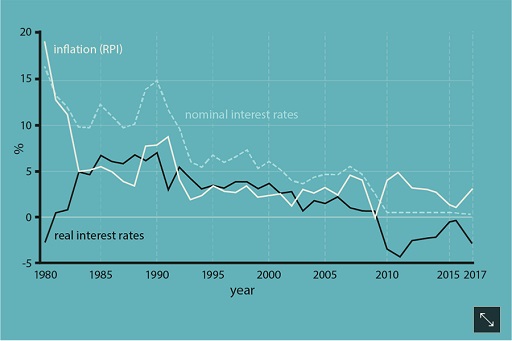

Real interest rates are interest rates that have been adjusted to take inflation into account. Looking at the graph, you’ll see that when inflation is higher than the nominal interest rate, real interest rates are negative (as they were in 1980/81 and again from 2010). Real interest rates are at zero when the rate of inflation and the nominal interest rates are the same; and they are positive when the nominal interest rate exceeds inflation.

Real interest rates were low in the 1990s and 2000s, falling from 7% in 1990 to just under 2% by 2004. Subsequently they fell further. By 2013 the fall in the (nominal) official interest rate to a historical low of 0.5%, combined with price inflation of 2.7%, resulted in negative real interest rates of -2.2%.

So, if you earn a nominal rate of interest of 1.5% on your savings and price inflation is 2%, you are actually getting a real interest rate on your savings of -0.5% – a negative rate of return. Such a situation where real interest rates are negative is clearly adverse for savers. However it is good news for borrowers if the cost of borrowing is negative in real terms.

Unsurprisingly, the low interest rates offered on savings in recent years have encouraged some households to reduce their debts – particularly credit card debts which have relatively high interest rates – by reducing their savings balances.

Most mainstream lenders link interest rates, including mortgage rates, to the official rate of interest, and so the cost of debt, including mortgage debt, declined over this period. This is another reason why debt levels may have risen in the 1990s and until 2007.

After 2007 the relationship between the official rate of interest and the cost of debt products was altered by a widening in the margin between them. Nevertheless, in the mid 2010s interest rates on mortgages and many other debt products were historically low.

4.2 Annual Percentage Rate (APR) of interest

In this section, you'll find out more on interest and the choices for borrowers. You'll also take the credit scoring test, find what opens and closes the door to getting a loan and explore the links between credit quality and interest rates on debt.

You have seen that borrowers have to repay to the lender both the principal sum and the interest. On top of this there are often extra costs. Some of these costs arise from fees that may have to be paid on obtaining a loan and, under certain circumstances, on repaying the loan before the end of the term.

- Arrangement fees paid to the lender: usually flat-rate, one-off fees charged when the loan is first taken out. Sometimes they may be added to the loan.

- Intermediary fees: may be paid when a borrower deals with a broker rather than directly with a lender.

- Early repayment (or ‘prepayment’) fees: may have to be paid to a lender if a loan is repaid early. The argument used by lenders is that earlier repayment can incur additional costs. In the case of personal loans, early repayment charges mean the lender gets a share of the interest that would have been paid had a borrower kept the loan for the full term.

- Tied insurance: taking out insurance (for instance, payment protection insurance, life insurance, home insurance) may be required with a loan. In other cases, insurance may be optional, although this is not always made clear to borrowers, who may end up paying for inappropriate policies.

Given all these different potential charges, and the different methods of calculating interest, it’s important to have a good means of comparing the total cost of debt on different debt products. Fortunately, in the UK there is a way of ensuring a fairly accurate ‘like-for-like’ comparison and of assessing which debt product is most appropriate. This is known as the Annual Percentage Rate (APR) of interest.

The APR accommodates interest and those charges, discussed above, that are compulsory. It does not include optional charges, such as buildings insurance, that are not required as part of a mortgage package or contingent charges, such as early repayment fees, that would become payable only in situations that are not applicable to all lenders. The APR also takes into account when the interest and charges have to be paid. The method for calculating the APR is laid down by the Consumer Credit Act 1974, as amended by the Consumer Credit Act 2006. Generally, a low APR means lower costs for the borrower.

The APR should be seen as only a reasonably standardised guide for comparing one loan with another based on their total cost. APR is not a perfect measure of loan costs. As mentioned above, it does not include costs that are not a compulsory part of the loan. In 2003 the Parliamentary Treasury Select Committee report into credit and store cards found that there were, in practice, two different precise methods used to calculate the APR, and ‘up to 10 different ways in which charges are calculated, meaning that users of cards with the same APR can be charged different amounts’ (UK Parliament, 2003). The Department of Trade and Industry responded by publishing regulations that tightened up the assumptions that could be used in the calculation of the APR.

4.2.1 Types of interest rate

Interest rates can be set in a number of ways.

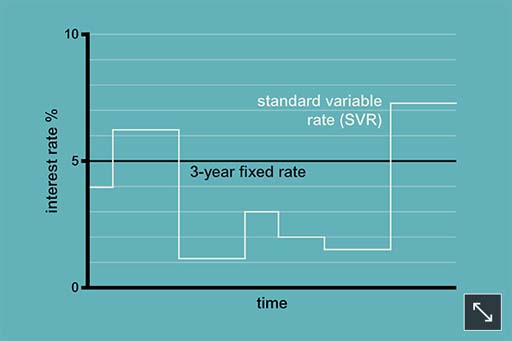

- A variable rate, which can move upwards or downwards during the life of the loan. In the UK variable rates usually move in tandem with movements in the official rate of interest. Some products (called ‘trackers’) are specifically linked to specific rates of interest such as the official Bank of England rates (Bank Rate).

- A variable rate with a ‘floor’. This is the same as a variable rate except that the rate cannot fall below a defined minimum level, known as the ‘floor’.

- A fixed rate where the rate is determined at the start of the loan and remains unaltered throughout the fixed-rate term. The rate will be based on what the lender has to pay for fixed-rate funds of the same term.

- A capped rate where the rate cannot rise above a defined maximum (the ‘cap’), but below this ‘cap’ it can move in tandem with movements of official interest rates. A variation to a capped-rate loan is a ‘collared’-rate loan where rates can move in line with official rates but cannot go either above a defined maximum (the ‘cap’) or below a defined minimum (the ‘floor’). Such products usually require the payment of a fee to the lender at the start of the loan.

Most commonly, personal loans are set at a fixed rate; credit card debt and overdrafts are set at a variable rate; while mortgage lending is split between the four interest rate forms defined above.

Households with variable-rate mortgages are, along with most of those with credit cards and overdrafts, at risk from increases in interest rates. As mortgages account for a large proportion of personal debt, it is easy to see why the UK economy can be easily affected by even relatively small movements in interest rates.

You will explore mortgages in detail in Week 6.

4.2.2 Interest rates – fixed or variable?

Activity 2

Under what circumstances do you think it might be attractive to borrow at (a) a fixed rate of interest and (b) a variable rate of interest?

Discussion

Assuming that borrowers have a choice and want to pay as little interest as possible, choosing a fixed rate may be preferred if rates are expected to rise, and a variable rate may be preferred if interest rates are expected to fall.

However, to assess which would be cheaper requires a forecast of how rates will move during the life of the loan, and making such forecasts is difficult because it is difficult to predict future rates of inflation and interest rates. In addition, the choice may reflect the borrower’s household budget. For example, households on a tight budget may choose a fixed rate because this would provide certainty of monthly expenditure.

What about your own debts – have you borrowed at a fixed or variable rate of interest?

4.2.3 Individual interest rates

You saw earlier that the Bank of England determines the official interest rate. Yet this is not the interest rate that will be charged to individuals taking out different types of debt. Lenders will tend to take into account a number of factors when setting the rates for a particular individual.

One of the reasons for charging interest has been the need for lenders to have a return for taking the risk associated with not getting their money back. Customarily, the basic principle here would be that the greater the estimated risk of loss, the greater the interest charged. This means that ‘higher risk’ borrowers may be charged more interest than those who are deemed ‘lower risk’. In a similar vein, interest charges will vary according to the security offered to the lenders by the borrowers.

This brings us to the distinction between secured and unsecured debt. Secured debt is money that is borrowed against an asset such as a home. If the debtor fails to make adequate repayments the lender has the right to recoup the money it has lent by selling the asset. By contrast, unsecured debt is not backed by any specified asset. For these reasons secured debts will, other things being equal, usually have a lower interest rate than unsecured debts.

Another factor that may affect interest rates is the size of the loan. Sometimes, larger loans will attract lower interest rates than smaller loans. The extent of competition between lenders will also be a factor. Typically, the greater the competition between lenders, the lower the interest rate you would expect them to charge.

One question that arises from this is whether such factors can explain the different interest rates charged, especially the higher rates often charged to people on much lower incomes. A Citizens Advice Bureau survey, for instance, found that APRs charged to clients with debts owed to money lenders and home-collected credit providers ranged from 25% to a staggering 360%, while interest rates charged on mainstream credit card debts ranged from 9.9% to 25.4% and on bank loans from 8% to 32.9% (Citizens Advice, 2003).

For many on low incomes, mainstream loans are simply not available because they fail the credit scoring tests such lenders apply. The result is that many have no option other than to borrow from non-mainstream lenders, whose high rates reflect both the risks involved in lending to those on low incomes and the recognition that such borrowers have few, if any, alternative options if they need a loan.

A Citizens Advice Bureau in Hampshire reported that their clients, a couple with two children, had taken out a £500 loan to repay their rent arrears which were the subject of possession proceedings. The total cost of the loan was £800 in total, with a 60% rate of interest. A West of Scotland Citizens Advice Bureau reported a client couple who had over £16,000 in debts. The couple had two recent loans from doorstep providers, both granted within two months of each other. The first loan was for £500, with a £275 interest charge. The second loan was for £100 with a £55 interest charge. These loans were being used to help meet the income shortfall on existing credit agreements (Citizens Advice, 2003, pp. 27, 28).

One alternative for those on low incomes is to see if they can borrow money from credit unions. These organisations do provide credit for those on low incomes – typically at interest rates higher than those charged by mainstream lenders but certainly lower than those charged by money lenders and the so called ‘payday lenders’. You’ll look at these types of lenders in a little more detail later this week.

4.2.4 The credit scoring game

Take a look at the credit profiles of Bill, Dave, Jo and Rajeev below. Who has the best credit score and who has the worst? Can you place them in their credit score order and explain your reasoning?

| Bill | Dave | Jo | Rajeev | ||

| Age | How old are you? | 20 | 19 | 39 | 40 |

| Employment | How would you describe your work? | Semi-skilled | Unskilled | Professional | Skilled |

| How long in current employment? | 2 years | Not employed | 5 years | 19 years | |

| Marital status | Single/married/separated/divorced/widowed? | Single | Separated | Married | Married |

| Children | How many? | No children | 1 child | No children | 1 child |

| Bank account | Do you have one? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Credit card | Do you have one? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Housing status | Home owner or tenant? | Furnished tenant | Furnished tenant | Furnished tenant | Owner-occupier |

| How long at your current address? | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years | 4 years |

4.2.5 Credit scores – the outcome

How did you do? What order of credit worthiness did you put our four borrowers in?

First you should note that the credit scoring models employed do vary from one institution to another. This means that the scores they generate can vary accordingly when applied to the same applicant.

The key things that score well though, besides having a good or high level of household income, are factors that infer stability and orderliness in the financial affairs of applicants. So stability of employment and in domestic residence scores well. Being an owner-occupier does too – even when the borrowing sought is not going to be secured against the property. Being older helps as you may be able to demonstrate a record of credit worthiness that stretches back over decades. Having fewer children also helps as it implies lower household expenditure commitments. Being in a professional job also helps as this is likely to reduce the risk of having periodic gaps in employment that reduce household income. Having a bank account and credit cards also help – particularly as they demonstrate that credit scoring tests have been ‘passed’ on previous occasions. Being married is positive for your score – being divorced is negative given, again, the inference of these when it comes to the stability and robustness of household finances.

By contrast being young, having a large number of dependants, living in rented accommodation – particularly if there is a record of moving home regularly – having a poor employment record and limited existing access to banking facilities are generally bad news when it comes to a credit score. Such factors provide no comfort about the solidity and orderliness of household finances, implying that lending to such applicants is risky. Additionally it is less likely that such applicants would have been able to build up a long term record of proven credit worthiness. Lending to those with a poor credit score may still take place, but the interest rate charged may be higher – perhaps materially – to reflect the risks involved.

The assessments of credit rating agencies are, though, not impressionistic. They are underpinned by data analysis of statistical relationships between aspects of social status and evidence of credit defaults.

So our model produced the following credit league table ranking:

- Rajeev

- Jo

- Bill

- Dave.

4.3 Meet the lenders

In this section, you will meet the lenders and their debt products, use the financial planning model to guide your borrowing decisions for those ‘big ticket’ purchases and find out the best tips for making sure that the pitfalls of borrowing are side-stepped.

Here Jonquil Lowe, personal finance expert at The Open University, presents a tour of the lending industry in the UK.

Transcript

Although the global financial crisis, which began in 2007, wrought havoc with the UK financial services industry, the sector has continued to be dominated by banks. This domination had been reinforced by the conversion of most of the large building societies to banks in the 1980s and 1990s – although all those that did convert were subsequently either acquired by other banks or, in the case of Northern Rock Bank and parts of Bradford & Bingley Bank, taken into public ownership during the financial crisis.

4.3.1 Borrowing can take many forms

Here’s a run-down of the most common forms of borrowing.

Overdrafts: a flexible means of accessing debt on a bank current account, up to a limit approved by the lender. Unapproved overdrafts normally attract penalty fees and high interest charges.

Credit cards (including store cards): their credit limits are set by the lender and normally require a minimum amount to be repaid each month – typically between 2% and 5% of the balance of debt. They may offer a short period of interest-free credit until payment is due. Credit cards vary widely in the interest rate charged on the balance that is not paid off, and some have an annual fee attached, although many do not. Store cards are a form of credit card used for buying from specified outlets. They tend to have much higher interest rates than credit cards.

Charge cards: can be used like credit cards to make purchases and obtain approximately two months’ free credit between purchase and paying off the outstanding amount. Charge cards differ from a credit card in that a borrower is required to pay off the entire balance each month. The two-month free credit period arises when the charge card bill is sent out monthly, with a further month in which to settle the bill. A fee may be payable for the card.

Personal loans: loans made to individuals, typically with terms of between one and ten years. They may be either unsecured or secured against a property (such as a house) or other assets. Unsecured personal loans are not contractually linked to any assets the borrower buys. These are available from credit unions, banks, building societies, direct lenders and finance companies.

Hire purchase (HP): a form of secured debt where payments (interest and part repayment of the principal) are made over a period, normally of up to ten years, to purchase specific goods. The legal ownership of the product only passes to the borrower when the final instalment has been paid.

Mortgages: loans to purchase property or land, which are secured against these assets. Debt terms for mortgages are normally up to 25 years. There are many types of mortgage and it’s possible to fund spending through equity withdrawal. Since the financial crisis, however, lenders have become more cautious about equity withdrawal, particularly in the wake of the decline in average house prices after 2007. We look at mortgages in more detail in Week 6.

Alternative credit: these are the areas of sub-prime lending described earlier, and include buying on instalments through mail-order catalogues, doorstep lending and ‘payday lending’. Commonly, interest rates are high and there are heavy penalties for late payment.

Peer-to-Peer (Peer2Peer) lending: this is an emergent form of lending in the UK and involves savers pooling funds for on-lending to individuals and businesses. This form of lending, arranged through intermediaries like Zopa and Financial Circle, circumvents banks and other conventional lenders.

4.3.2 Making borrowing decisions

Philip wants to purchase a music system costing £1000. If you assume that he cannot simply fund the purchase out of his monthly budget, his options include:

- using existing savings

- building up savings first, then purchasing the item later

- using a mixture of savings and debt

- taking out a debt of £1000.

The option Philip chooses will obviously depend on a number of factors including, crucially, his initial financial position.

For the rest of this week, you’re going to help Philip make the best choice. Start by running through some generic issues related to each option.

Option 1 involves using existing assets held as savings. If Philip has savings, he could draw on these to buy the music system. When deciding whether or not to use his savings, Philip may think about opportunity cost – the savings he uses to buy the music system will not then be available to purchase something else. He will also have to give up the interest he would have received on the savings spent on the music system. He might want to compare debt costs with the loss of income on his savings.

There are generally two reasons why the interest paid on a debt may be rather higher than income earned on savings.

- Savings products and debt products are provided by the same institutions – such as banks and building societies – and these institutions make their profits from the difference between the interest rates on the two products. In normal circumstances it’s likely that the interest rate for debt will be higher than the rate earned on savings.

- Interest on savings will be taxed as income unless there is a means of sheltering the earnings – for example, by saving in tax-exempt products. If savings are taxed, the rate of interest received after tax is likely to be lower than the interest paid for borrowed money. (Savings are covered in more detail in Week 5.) So, other things being equal, using existing savings will usually be cheaper than taking out debt to fund a purchase.

Option 2 is to build up savings before purchase. Again, this depends on having disposable income to allow savings to be built up. It also depends on Philip being prepared to defer the enjoyment associated with having a music system for the time it takes him to build up the savings. For the same reasons as Option 1, this second option is most likely to be cheaper than using debt to fund the purchase.

Options 3 and 4 both involve taking on debt. For the reasons already given, it’s likely that using a mixture of savings and debt would be cheaper than funding the purchase solely through debt.

For the sake of clarity, assume that Philip chooses to borrow the full £1000.

4.3.3 Affordability

What does Philip need to think about?

Think back to the financial planning model. If Philip were to apply the ‘Stage 1: assess the situation’ part of the model, what are the issues he would need to consider?

Philip assesses the situation

Using as a guide the assessment part of the financial planning model, Philip would need to consider the relative importance of buying the music system within the wider context of his existing goals.

He would need to think about the constraints on his resources, and calculate whether he can afford the repayments within his household budget. In thinking through affordability, Philip should consider the possibility that his circumstances may change. For instance, if his household income were to fall or be interrupted during the term of the loan, would Philip still be able to afford the repayments? This assessment of affordability is essential – and it will, in any case, be undertaken by the lender when scoring Philip’s creditworthiness ahead of approving a loan.

4.3.4 Tips when borrowing

With good planning and financial management you can avoid debt problems. If you do encounter problems, take action to address them. Do not wait for what may be minor financial issues to escalate to major problems for you and your family.

Here are some expert tips on how to deal with borrowing issues.

- Get free advice.

- Don’t panic or ignore the problem: unopened bills won’t go away.

- You can’t ignore your debts. Better to pay a small amount than nothing at all – those you owe money to may be prepared to accept low repayments.

- If you’re struggling with store or credit cards, stop using them.

- Work out a realistic budget that covers all your income and spending. Check whether there are any benefits or tax credits you’re entitled to that you’re not getting.

- Decide which debts take priority – like mortgage or rent – and which cost you most through penalties or higher interest rates.

- Only agree to pay off debts at a rate that you can keep up – don’t offer more than you can afford.

- Contact those you owe money to as soon as possible. Let them know that you’re having problems. Many companies will be helpful if you talk to them.

- If organisations won’t accept your repayment offers, seek advice.

- If you get a threatening letter, get advice from your local Citizens Advice Bureau or trading standards service.

- If a debt collector calls at your home, you don’t have to let them in. If you want time to get advice, arrange a later appointment. If a debt collector or lender harasses you, contact your local Citizens Advice Bureau or trading standards service.

- Check if a loan will be secured on your home. If it is and you do not keep up repayments you could lose your home. If you do not understand the terms of a loan, get advice.

- If you’re thinking of taking out a new loan to pay off debt, make sure you find out the total cost of the loan, not just the monthly repayments.

- Think very carefully before borrowing more to pay off your debts. Get impartial advice and don’t rush into signing anything you don’t understand.

- If you are thinking of using a fee-charging debt management company, then make sure you understand exactly what you’re signing up to – check what fees you’ll be paying to the company and how long it will take you to pay off your debts.

- Keep copies of all letters you send and receive about your debts.

The Managing my money team conducted a poll of The Open University’s personal finance tutors to ask them what they thought were the most useful of these tips. The four deemed most helpful were:

- work out a realistic budget that covers all your income and spending

- don’t panic or ignore the problem

- decide which debts take priority

- contact those to whom you owe money.

Week 4 quiz

This quiz allows you to test and apply your knowledge of the material in Week 4.

Complete the Week 4 quiz now.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you're done.

Week 4 round-up

In this week you’ve looked at the subject of debt – a financial product with which virtually every household is familiar, from an outstanding balance on a credit card bill to a mortgage on a property.

The focus has been the cost of debt, introducing you to the key financial subject of interest rates. You’ve looked at the factors that determine the interest rate you pay when you borrow money, taking in on the way the subjects of official interest rates, real interest rates, the compounding of interest and APR.

Interest rates come up again in the next week, where you look at the ways that people can invest their money. So while this week has dealt with the subject of debt, which is known as a liability, Week 5 looks at savings and investments, which are collectively known as assets.

You can now go to Week 5: Savings and investments

References

Acknowledgements

This unit was written by Martin Upton and Jonquil Lowe.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated in the acknowledgements section, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this unit:

Unit image

Figures

Figure 5 © CORBIS/Reuters

Figure 6 © iStockphoto.com/GlobalStock/szefei/annebaek

Figure 7 © iStockphoto.com/GlobalStock/szefei/annebaek

Figure 9 © iStockphoto.com/rook76

Figure 10 © iStockphoto.com/CEFutcher

AV

What determines the level of interest rates? © BBC

Meet the lenders (contains archive © BBC)

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

You can now go to Week 5: Savings and investments

Don't miss out:

1. Join over 200,000 students, currently studying with The Open University – http://www.open.ac.uk/ choose/ ou/ open-content

2. Enjoyed this? Find out more about this topic or browse all our free course materials on OpenLearn – http://www.open.edu/ openlearn/

3. Outside the UK? We have students in over a hundred countries studying online qualifications – http://www.openuniversity.edu/ – including an MBA at our triple accredited Business School.

Copyright © 2014 The Open University