Partnerships and networks in work with young people

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 6:51 AM

Partnerships and networks in work with young people

Introduction

Partnerships and networks can emerge at a number of levels. For example, the initial contact which leads to partnership might come from young people themselves talking about their needs and interests and feeding these back to workers. It might also come from conversations between workers at inter-agency training sessions or conferences, where shared interests are identified and an exchange of ideas and information can enrich the practice of both. This in itself would be a positive outcome of networking, but if taken further it might lead to a more formal partnership between organisations. So working in partnership can be small-scale, local and temporary, and it can also involve formal arrangements between one or more organisations working together across regional boundaries over a period of time.

You will probably be aware from your own experience of practice, as well as from your reading, that there is a significant emphasis on partnership working in current debates and discussions about practice in work with young people.

As Howard Sercombe comments:

Internationally, there has been increasing pressure for different professions to work together. This [is] a good thing: young people deserve to have the best expertise available when they need it, and youth workers need to be well connected and skilled at making the right referral and in working together on issues with other professionals …

Partnership and collaboration has developed as a core practice criterion in youth policy over the last decade … It isn’t just in youth work either: collaboration is also in fashion internationally, with schools, universities, government departments and even private businesses needing to demonstrate that they are working with other people.

The LEAP framework for project planning also emphasises the importance of partnership as one of its five principles for project working (The Scottish Government, 2007).

In this course you will be examining the range of issues that partnership working presents for practitioners working with young people. You will also be considering ways in which you can approach developing partnerships in your own practice, particularly in the context of your project.

We begin by examining the term ‘partnership working’ and other terminology that is used to describe the ways in which different organisations and practitioners from different agencies work together.

We then move on to consider the different levels at which partnership working might operate and the policy context in which partnership working has developed. We invite you to think about the benefits – as well as the potential challenges and dilemmas – that working in partnership can bring. You will be building on your previous learning about the nature of leadership and of organisations as you explore the issues that arise when people from different organisations – with their different structures and cultures – try to work together.

Finally, we look at ways in which you can develop your own professional practice in these areas of work and ‘make partnerships work’, including as you begin to undertake your project.

Partnership working takes effort. It is complex and demanding and can be slow and frustrating. However, it also has the potential to be a positive and exciting area of professional practice, challenging the way you think and allowing you to learn from being exposed to different ways of working and different professional perspectives. Michael Bracey, for example, reflects on how partnership working has given him opportunities to be part of creating real change for young people, and provided him with some of the most significant developmental opportunities in his career as a youth worker:

Partnerships can provide a way through bureaucracy to a place where people can really be visionary. They can provide a laboratory for new ideas, a place where risk taking is acceptable and where alternative ways of working can be explored.

Bracey is writing from a particular perspective, as someone who has a senior role in a local authority service. Your own view of partnerships on the ground may be less rosy, and you might be much more sceptical. Nevertheless, we hope that studying this course encourages you to find opportunities to be creative in partnerships, to make them fit with the way you work and, above all, to continue to focus on ways in which outcomes and opportunities for young people can be improved as a result of the work that you do in partnership with others.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 2 study in Education.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

describe and discuss the principles of partnership working

review the context and policy background that informs partnership working, particularly as it relates to practice with young people

identify some of the benefits that can arise from partnership working, as well as the challenges it may present for practitioners

identify ways of developing partnership working practice.

1 What do we mean by ‘working in partnership’?

Partnership working means different things to different people. The term is used to describe a wide range of organisational arrangements and ways of working, from informal networking between individuals, to work in much more formal partnership structures.

1.1 Definitions and metaphors

Dictionary definitions of ‘partner’ make reference to partners in a business, a marriage (or established cohabiting relationship) or in a dance.

Metaphors can be useful in exploring things from different angles. Your possible initial impressions of partnership might be of a formal, contractual undertaking, where people are looking for competitive advantage: a cosy, trusting relationship based on give and take; or of a well-coordinated precision – a dance in which each partner knows the complementary steps (though there is always the risk of treading on each other’s toes).

You might develop these metaphors further. For example, there are different kinds of dance – each with different implications. Partners might be mainly dancing alone, or they might be dancing in a group, communicating and picking up new steps from each other – just as some partnerships consist mainly of individuals, within two or more agencies, sharing experiences in an informal way, sparking ideas off each other and perhaps helping each other out from time to time. Dancers may be coordinating their movements with others, as partners might establish a pattern and a set of ‘rules’ that govern their work. Alternatively, a caller might be keeping them in step; a concern expressed by some small voluntary organisations is that they have to dance to the tune called by a larger organisation with more ‘clout’. People might also be moving in and out of the dance, just as partners move in and out of partnerships and have different levels of commitment that may vary with time.

Developing the metaphor of partnership as a marriage, marriage may be a state that is freely entered into, where people make a very conscious choice to be together and are willing to work through any difficulties they might encounter. The marriage might be one of convenience, which each partner has entered into willingly with a view to what they will each get out of the relationship. Or it might have arisen ‘because one agency believes it has something to gain by having influence over the other. This is a model of partnership on the basis of “putting mutual loathing aside to get your hands on the money” (Alex Scott-Samuel …) rather than one that leads to shared benefit’ (Miller et al., 2010, p. 42).

Alternatively, the marriage might be the result of other people’s decisions, in the same way that partnerships might be the result of decisions made outside organisations; for example, because of government edict. Partners may be obliged to participate with other partners who have very different values, priorities and ways of working.

We hope that these metaphors help to highlight particular dimensions of partnerships: the extent to which partners are working in parallel or in an integrated fashion; the level of formality in the agreements between them; the levels of risk and reward for all involved; the extent to which the partners are committed to the relationship and for what ends; whether there is a clear leader or whether decision making is truly collaborative; the stages that the relationship might go through; and the feelings that accompany any work with people.

We return to the different dimensions of partnership later in this section. First, though, we ask you to consider your own understanding of ‘partnership’, based on your experience of practice.

Activity 1: Definitions and characteristics of ‘partnership’

- What does the term ‘partnership’ mean to you? Write down the first impressions that come into your mind when you think of the term ‘partnership’.

- Think of a piece of partnership working that you are familiar with – either personally or something that you have heard about or read about. What makes you call it partnership? Use a table similar to Table 1 below to jot down your reflections. We have included an example to get you started.

| Your partners | What makes you call it a ‘partnership’? |

|---|---|

| Example: I work with the police and the Neighbourhood Support Team. | Example: We have regular meetings to talk about young people and issues affecting them and their behaviour – although their agenda is often very different from mine. |

Comment

First impressions of partnership are likely to fall somewhere on a spectrum from cooperation, harmony and mutual respect at one end, to competition, conflict and power struggles at the other.

Your impressions may well have affected the way you defined partnership, whether you see it as something that is based on cooperation, mutual trust and respect for different people’s contributions, or something that is characterised by more negative attitudes and behaviour – for example, agencies vying for influence and resources.

For the purposes of this course, we have defined partnership working as:

Two or more parties working together towards a common goal, in a way that attempts to overcome boundaries between services; provide a coordinated response to the needs of young people; involve a fair allocation of risk, resources and benefits; and provide added value.

This is what Huxham (1996) called ‘collaborative advantage’ (deliberately intended to contrast with the more familiar term ‘competitive advantage’) in which:

- something is produced or achieved which no organisation could have achieved on its own

- each participant is able to achieve some of their objectives more successfully through collaboration than by working on their own.

You have now thought about definitions of partnership in general. In your experience of practice, and in your reading about practice, you may have come across a range of terms that are used to describe the way in which different organisations and agencies, and practitioners from different professional backgrounds, collaborate and work together. It is important to understand the potential significance of different terms.

1.2 Terminology

Vipin Chauhan, writing about partnership working in the context of the voluntary and community sector, comments that:

Increasingly, voluntary, community and public sector organisations are caught up in this frenzy about ‘partnership’, ‘multi-agency’, ‘inter-professional’ and ‘inter-agency’ working. Such terms are used almost daily without paying much attention to what they mean in reality …

In the audio-visual material that you will be looking at as part of this course, partnership working is referred to as ‘working across agencies’. In some cases, people have specific ideas about the differences between different terms. For example:

- Inter-agency working usually refers to arrangements between two or more agencies for planning, implementing and evaluating joint projects or longer pieces of joint working.

- Multi-agency working refers to representatives from a number of agencies coming together to look at a problem in a holistic way.

- Multi-disciplinary working refers to teams made up of people from a range of professional backgrounds.

Conversely, the catch-all term ‘partnership working’ may be used to describe all of these ways of working – and others – in order to describe varying degrees of joint working, collaboration and cooperation:

Trying to understand how partnerships work can be difficult. It is not helped by the lack of a clear definition of the term, and the enormous variation in the types of association to which the term is applied. On reading the growing amount of literature on the subject, we soon realise that the term seems to be applied to any kind of relationship between different agencies.

Some writers (e.g. Roberts et al., 1995) have suggested that this ambiguity is one of its political attractions – it can mean whatever anyone wants it to mean. Because of this confusion an important first stage in any new venture is to clarify the purpose and nature of that particular piece of partnership working. It is also important to recognise that the landscape of work between agencies and between different professionals is still evolving and developing as we write this course, and that the language used to describe this area of practice is also likely to evolve and develop with time and to vary with context – for example, depending on the nation in which you are working.

One of the attractions for us of using the term ‘partnership’ is that it can also be used more widely still to represent the traditional values in youth work of adopting a participative approach to working with young people: treating them as partners in their own learning rather than as ‘clients’ to be ‘done to’.

1.3 Dimensions of partnership working

We will now look in more detail at the range of practice and of organisational arrangements known as partnership working.

Below are accounts from two practitioners, who describe their experience of partnership working and their understanding of the term.

Sabrina

Sabrina works as a youth development worker for a local authority in the English Midlands. She manages a small team of part-time youth workers and between them they provide a range of daytime, evening and weekend opportunities for young people living in the local area.

I’m based in a youth and community centre which shares a site with a secondary school, and the school is a key partner for me. I’ve established a good relationship with the head and have worked alongside teachers in joint projects. For example, I’ve been working with the teacher responsible for citizenship and, with a group of post-16 students, developing a peer education project on homelessness. The school funded some of the work and I’ve put in my own time and some additional hours for a part-time worker. Some of my team now operate a sexual health service in the youth centre at lunchtime – in cooperation with the school nurse and a specialist sexual health worker in the voluntary sector. I’ve also been working with an education welfare officer who supports young people in care – encouraging them to take part in youth work. I’ve just had a young woman in care on work experience for a week, which was good. I’ve also got some good links with the sports development worker in the district council. I don’t really get involved in strategic stuff – though my manager does.

Mick

Mick works for a community organisation and is based in a community centre on an estate in the West Midlands. He has worked there for a long time and has developed strong networks in the neighbourhood surrounding the centre.

I think of myself very much as a neighbourhood-based youth and community worker. I’ve worked on this estate for a long time and I work closely with local agencies, including housing officers and the tenants and residents organisation. Health is a big issue for residents and I work closely with health and drugs and alcohol agencies in order to be able to respond. Community safety is also high on the agenda. I’ve been supporting young people in meetings with the police where they’ve been expressing their views about how the police treat them and how they’re always being moved on. I chair the estate’s inter-agency forum, which brings agencies and community representatives together. In my role it’s also important to keep up with strategic developments across the city. I’ve managed to position the work of the centre so it has been able to respond to city-wide agendas and priorities – in the past we’ve received significant funding to support some of the work that we’ve done, but getting funding is much more difficult now because of cuts in different organisations’ budgets.

Activity 2: Differences between partnerships

Using these practitioner accounts and any of your own experiences, try to identify some of the ways in which individual partnerships might vary and jot these down. For example, you may have noticed how Sabrina seems to be involved in partnerships with other practitioners working with young people at local level, while Mick is involved in partnerships operating more strategically.

Comment

You might have noted some of the following differences.

Partnerships vary in terms of the themes and issues they are addressing and in their breadth of focus – from partnerships with a very specific focus, for example drugs and substance misuse, through to partnerships addressing a much broader set of issues, for example regenerating a town or an estate.

Partnerships also vary according to the range and nature of the partners involved, including whether they involve statutory, voluntary/third-sector and/or private sector organisations and whether young people and other community representatives are also involved.

Partnerships vary in their time span – they may be focused on one-off, short-term projects, or develop into longer-term plans for working together.

The impetus for partnership working can vary – it may come from the bottom up or the top down. In other words, partnership might have developed as a response to needs and issues identified locally or as a result of a ‘top-down’ directive – for instance, in response to a new government policy or piece of legislation, in which case engagement might be compulsory rather than voluntary.

The Crime and Disorder Act of 1998, for example, required crime and disorder partnerships to be set up in England and Wales and specified the agencies that should be involved. In other cases, people seek out potential partners whom they know have a common interest in developing provision for the young people they are working with, or who have common values.

Partnerships might be planned or emergent. Some partnerships, like projects, arise because people have a specific outcome in mind. Alternatively, ideas about what you might do or achieve as partners might evolve over a period of time and as relationships develop.

Some writers on partnership focus almost exclusively on partnership in the context of formal organisational arrangements, often at a strategic level, but others take a broader perspective, highlighting the importance of informal networking. We now move on to think about these different levels of partnership.

1.4 Levels of partnership

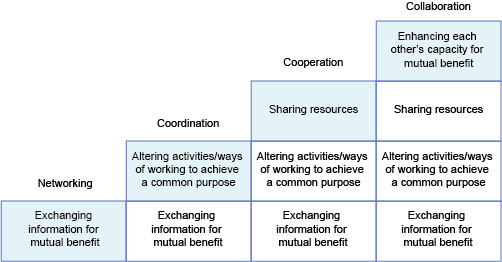

As we have seen, partnership working can involve different levels of formality and commitment, from work based on quite loose and informal networks at one end of the spectrum, through to working arrangements based on formal agreements and organisational structures at the other. Himmelman (1996) has developed a model of partnership that he uses to explore these different levels of commitment, which he sees as a continuum. In Figure 7.1 we illustrate his model using the idea of a series of levels.

A diagram of a model of partnership illustrated using a series of four levels or steps. The lowest level is labelled ‘Networking’, is one layer deep and contains the wording ‘Exchanging information for mutual benefit’. The second level is labelled ‘Coordination’, is two layers deep and contains the wording ‘Exchanging information for mutual benefit’ on the bottom layer and ‘Altering activities/ways of working to achieve a common purpose’ on the top layer. The third level is labelled ‘Cooperation’, is three layers deep and contains the wording ‘Exchanging information for mutual benefit’ on the bottom layer, ‘Altering activities/ways of working to achieve a common purpose’ on the second layer and ‘Sharing resources’ on the top layer. The fourth, and highest, level is labelled ‘Collaboration’, is four layers deep and contains the wording ‘Exchanging information for mutual benefit’ on the bottom layer, ‘Altering activities/ways of working to achieve a common purpose’ on the second layer, ‘Sharing resources’ on the third layer and ‘Enhancing each other’s capacity for mutual benefit’ on the top layer.

Networking is the most informal level of partnership working and involves exchanging information for mutual benefit. There needs to be a minimal level of trust and willingness to share information, and the contacts are usually made informally, person to person rather than organisation to organisation.

Himmelman highlights the importance of this person-to-person contact in networking, pointing out that, ‘it is clearly more helpful to be able to have a contact person through whom you can get the information required and, as necessary, have a continuing dialogue of mutual benefit’ (Himmelman, 1996, p. 27).

Coordination goes a step further. As well as exchanging information for mutual benefit, the partners agree to alter their activities or ways of working in order to achieve a common purpose. Coordination can help to address problems of fragmentation, overlap and duplication in services. For example, Sabrina might identify, though her conversations with other organisations, that they are each offering similar provision for young people on the same night of the week. As a result of exchanging information, they might decide to open on different nights, or arrange to diversify and complement each other in order to give young people a wider range of options.

Cooperation moves the partners up a step. In addition to exchanging information and coordinating activities for mutual benefit and to achieve a common purpose, organisations might share resources – including money, staffing and buildings.

At the top of the staircase, at the level of collaboration, the step of enhancing each other’s capacity for mutual benefit is added to the earlier ones. At this level, each person or organisation works at helping their partners to become better at what they do. Mick’s advocacy work might come into this category. Thinking of the needs of others, as well as one’s own self-advancement, is generally considered to be a sign of maturity (Himmelman, 1996) – hence the placement of this form of partnership at the top of the staircase, subsuming the other activities of networking, coordination and cooperation.

Himmelman (1996) argues that any of the four levels of partnership might be appropriate in different circumstances. He offers three key factors that influence the decision, the three Ts of: Time (how much is available), Trust (how well the people involved know and trust each other) and Turf (how high is the potential for turf wars, based on different values and purposes, readiness for power sharing, cultural differences, and so on).

Activity 3: Levels of partnership in practice

Look at the video, ‘Planning inter-agency work’, below. It shows practitioners from two organisations in London meeting to discuss how they might work together.

As you watch, make notes on the following points:

- Why have the two agencies decided to work together?

- What do they want to achieve? Have they any common goals?

- What different knowledge and skills can each organisation contribute?

- What resources have they agreed to share?

- What other practicalities need to be agreed?

- At what level of partnership are they operating?

Transcript: Wandsworth Youth Service: Planning inter-agency work

GILLIAN THOMAS: I'm hoping Junior has got some more ideas in what we can with them if we do it.

JUNIOR NELSON: Charline could possibly look at getting some video footage we've done, especially addressing the antisocial behaviour.

CHARLINE KING: Is it young people that you know of on the estate that we're going to, or is it just going to be handed out?

GILLIAN THOMAS: Could Shaquille do the leaflet and liaise with Charline? I will speak to Takeesh, All right. So first of all, I've got Tooting Grove. So if you tell me what you know.

JUNIOR NELSON: I know through the Housing Department and Vickie, because they're forwarding all the young people's names through they have problems with. They've come up with two names at the minute, two for antisocial behaviour. I think one's possibly, ASBO, they're looking at one-day ABC. The two young people that we know that attend our provision, so we need to really...

GILLIAN THOMAS: ... So you know these two young people?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah.

GILLIAN THOMAS: Do they actually live on Tooting Grove?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah.

GILLIAN THOMAS: Do you know if they go to the Tooting Grove Youth Club?

JUNIOR NELSON: I know one them definitely does.

GILLIAN THOMAS: Go to the youth club?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah.

GILLIAN THOMAS: OK. So what could we do?

JUNIOR NELSON: I know holiday's just gone. We had some of them through at our place, and even though they were too old, because they wanted to record some stuff in the studio. So if Takeesh was around, we could possibly bring some music equipment, for them record some stuff.

GILLIAN THOMAS: At the club?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah.

GILLIAN THOMAS: So are you saying then that maybe at Easter, if I try and get ahold of the people who hire out the building, we could do a day or two that, what would you like?

JUNIOR NELSON: Definitely...

GILLIAN THOMAS: ... Because I think they would like that, because I spoke to them not long ago. We had some parents in, and then I spoke to them in the evening, and music is one of the things they want to do.

JUNIOR NELSON: Because a couple of them have got a couple of groups, so they've got their songs already done. They just wanted them mastered, so.

GILLIAN THOMAS: I mean, I wouldn't mind at all paying for something to go on down this. Do you remember the thing we did at the triangle [INAUDIBLE] about a year ago? Why don't we go for something like that, where we do about three, four days?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah, and we'd have to split the days...

GILLIAN THOMAS: ... And Charline, you can be in charge of that.

JUNIOR NELSON: We'll have to split the days up, because if they're recording, then that's going to wholly specifically mean that group there at that time.

GILLIAN THOMAS: That's what I'm saying. For the Easter, I don't mind just going with a small project, just the music.

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah. That's not a problem. We could do music and video, because I know Charline's around.

GILLIAN THOMAS: OK, so music and video. Charline will be your person that's going to be working down there. What do you need from me for that?

JUNIOR NELSON: In terms of equipment, we've actually got the equipment.

GILLIAN THOMAS: You've got all the equipment?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah.

GILLIAN THOMAS: So equipment will come from you. Apart from Charline, do you need any other staff?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah, we probably need staff, because it's kind of labour intensive.

GILLIAN THOMAS: OK, how many young people do you want to work with?

JUNIOR NELSON: Specifically on the music at one time, you don't really need more than eight.

GILLIAN THOMAS: So about eight young people.

JUNIOR NELSON: But we can split the music, and they've got the football pen outside. Charline could possibly look at getting some video footage we've done, especially addressing the antisocial behaviour, or maybe do a small little video, Walk around the estate, and film the video of the estate, and that can lead into talking about acceptable behaviour.

GILLIAN THOMAS: You've got your people that's going to be doing the video, the whatever. What I would like to do is I would like to ask Takeesh if she could work.

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah, she would be one of the workers I'd like, because she's got experience with...

GILLIAN THOMAS: I find that what happens is like during the holidays, Takeesh is not able to work. I mean, that's my, that's in the past, what's been happening. So I'll ask Takeesh if she can work. If she can't work, you've got Charline. Do you need another worker or so? What do you want?

JUNIOR NELSON: If so, we probably would need another worker, because you can have a worker specifically doing music.

GILLIAN THOMAS: OK. Who's paying for the, for your workers?

JUNIOR NELSON: Me.

GILLIAN THOMAS: OK, so you're paying for your workers, and you want two workers from me, yeah?

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah.

GILLIAN THOMAS: So Charline, that would be you and somebody else. Maybe we could look at a male worker.

JUNIOR NELSON: Because we'll have, I'll have workers actually floating, doing other stuff, as well. What I'll also do is double-check with housing, to see if there's any more names have come through the last list that we need to catch up with.

GILLIAN THOMAS: OK. It's kind of a new territory to, to be starting down. This is the first time we are going to be, it's something on there apart from the day, so should we do this one first, and then see how it goes, evaluate that?

From that, we can kind of get an idea of the needs. If we, Charline, maybe you could use one of the questionnaires with the young people down there at that point, seeing what they would like, as well, so we have an idea what they would want. And we could do something ongoing, rather than just go down there once, do something, and come out again.

JUNIOR NELSON: Yeah. I think also trying to sort some kind of holiday... it's like a spin off from Asian vibes. There's a particular group of young Asian males that are sort of like known for getting into bits of problems in the community. We're trying to set up a men's only session for them.

GILLIAN THOMAS: There's a guy called Haruf, and Haruf works, say, on Sundays in Graveney Madrasah. Haruf also work in South London, South Thames College in Wandsworth. And Haruf works with some boys, some Asian boys, in the Tooting area that's into drugs and crime, and all kinds of things, boys of that age, 11 to 19.

And Haruf has always been looking for somebody to work with in youth work, or YIP or YOT, or somebody with these young people. That's a group that we can fund through PAYP, because these boys fall into that. So if I, I could give you Haruf's number, and you could get in touch with him. He would be a good person to get in touch with.

It was good, because what I really wanted, although I had about five agenda points, I really wanted to get something going in the Tooting Grove area. And Junior, most of the young people down there, Junior and his workers know them, because they work with them in sports. So getting Junior on board with me with that was going to be crucial in the young people attending.

So yeah, it's brilliant. It's brilliant that he's come along, and he's agreed to do this project with me, and it's not going to be just a one-off project. We're going to try and continue it as long as. But we're just going to do this first one, and evaluate it, and see what happens. So yeah, I got a result.

Comment

Gillian, Charline and Junior are meeting to discuss how they might work together in response to concerns about young people ‘hanging about in the streets’. By working together, they believe they can provide young people with something more positive to do. Each agency already has a relationship with at least some of the young people mentioned and it makes sense to try to work together in order to develop a shared response to needs.

They know, through their contacts with young people and with parents, that the young people are interested in music. They each have resources and skills to bring to the project, including access to recording equipment, premises and staff, and they each agree to make some contribution, including paying for additional staffing. This will be a pilot project, which they plan to evaluate as the basis for developing longer-term work together. They also discuss another potential piece of joint work, specifically targeting Asian young men who are ‘known for getting into bits of problems in the community’.

They mention a number of other agencies which might play a role in supporting young people and with whom they have contacts. These include the housing department, the further education college and a faith-based organisation, as well as relationships that they have with parents and ‘the community’.

After their meeting, Gillian reflects that she achieved what she wanted – ‘getting Junior on board’. She recognises that Junior will bring skills, contacts and resources that can help her to achieve more than she could just by working on her own. We can assume that Junior also sees benefits for himself, and for the young people he works with, as a result of developing joint projects with the youth service.

We suggest that the two organisations are beginning to work on the cooperation step – exchanging information and also planning to change their activities and to share resources (at least for the duration of this pilot project) in order to achieve mutual benefit for each organisation. They agree to evaluate the project afterwards. The outcome of this is likely to determine whether they continue to cooperate and share resources, or whether they go back down a step.

2 Why work in partnership?

One short answer to this might be ‘Because we have to!’ Depending on your role and the context in which you are working, working with others may be something that is required of you by your organisation or that you are required to do in response to government policy, and may be central to your practice.

We begin this section by examining the context and background to partnership working. We then go on to look at the benefits of working in partnership – for young people, for organisations and for communities.

2.1 Context and background to partnership working

The concept of different agencies working together for a common good isn’t something new. Work with young people and with communities has always involved some degree of collaboration with others, and there has been a recognition for some time that different professionals need to be able to work together effectively in order to meet young people’s needs. Before the advent of the welfare state, for example, local authorities worked alongside voluntary organisations to deliver welfare. Developments in the 1960s and 1970s, including education priority areas and the community development projects, combined a number of features of more recent partnership initiatives, including inter-agency working and community participation, and were targeted at areas seen to be most in need (Balloch and Taylor, 2001). The Thompson Report, which reported on youth work in England back in the early 1980s, also recommended that:

The Youth Service and other services dealing with young people should develop the means of working together. It is the responsibility of management to foster collaborative arrangements with other services, whilst respecting the independence and proper role of each. This will encourage the most effective use of funds, staff and facilities.

What is different now is the emphasis that recent governments have placed on the development of partnership working, particularly in relation to the delivery of public services.

Policy during the years of the Labour Government of 1997–2010 had a strong focus on joint working between agencies and on partnership across a wide range of public policy, including in education, health, regeneration, and crime and disorder. Partnership working became ‘the new language of public governance’ (Sullivan and Skelcher, 2002, p. 1). Partnership was a central theme in government approaches to work with young people, and work with children, young people and families more broadly, both at the level of policy coming from Westminster and within policy emanating from devolved governments in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, which increasingly had (and continue to have) legislative power in areas relating to work with young people.

Key policy drivers in partnership working in the field of work with young people in these years included work done by the Social Exclusion Unit (SEU).

2.2 Young people and social exclusion

The creation of the SEU was particularly significant in the development of partnership working in relation to work with young people – so much so that it was described by some commentators as the ‘de facto Ministry of Youth’ (Williamson, 2007, p. 36). It was set up soon after the Labour Government was elected in 1997 as a cross-government department aiming to help improve government action to reduce social exclusion by producing ‘joined up solutions to joined up problems’ (SEU, 2000). It created a series of policy action teams made up of government and non-government agencies.

The report of Policy Action Team 12 (SEU, 2000) considered ways in which government could improve policies and services to meet young people’s needs. It found a situation of fragmented policy and service delivery.

It also found that individual agencies tended to focus on their own individual objectives, with difficult issues that straddled boundaries not being adequately dealt with, or ignored. The picture was particularly gloomy for young people with the most significant problems and the most complex needs:

Young people get shunted from agency to agency because responsibilities are unclear. … As a result, young people can fall through the cracks in agency responsibilities, and services can appear contradictory, complex and inaccessible. … Young people with multiple risk factors often go without help.

It went on to recommend that there should be a cross-departmental approach to young people’s issues and youth inclusion, and that structures should be created to support cross-departmental and inter-agency working.

2.3 Partnership and safeguarding

The Green Paper Every Child Matters (ECM) (Chief Secretary to the Treasury, 2003) built on this thinking and analysis, identifying the need for agencies to cooperate and work together in order to improve children’s well-being. It identified five outcomes that were seen to be most important to children and young people:

- be healthy

- stay safe

- enjoy and achieve

- make a positive contribution

- achieve economic well-being.

Every Child Matters informed the Children Act of 2004 which led to the reform of children and young people’s services in England, with an emphasis on promoting cooperation between agencies in order to improve outcomes for children and young people (if you are interested in reading more about these policy developments, see the Every Child Matters website). A significant event in the lead-up to ECM and the Children Act, and one which was highly influential in changes in practice that followed from this, was the death of Victoria Climbié and Lord Laming’s subsequent inquiry into the circumstances surrounding it.

As Percy-Smith observes:

The focus on partnership working is not surprising given the long list of high profile failures to adequately ‘join-up’ policy and practice.

Victoria Climbié died on 25 February 2000, ‘the victim of almost unimaginable cruelty’ (DoH, 2003, p. 1). Her aunt and her aunt’s boyfriend were convicted of her murder a year later. The inquiry that followed found a catalogue of systemic failures, poor professional practice, and poor leadership and management at a senior level, including a ‘dreadful state of communications’ within and between agencies (DoH, 2003, p. 9), failures of record keeping and information sharing, lack of clear protocols between agencies, a failure to follow procedures, and confusions about responsibilities. It also highlighted poor relationships between staff from different agencies, a failure to understand each other’s role, barriers to communication created by the stereotypes different agencies had of each other, and agencies working to different agendas.

Lord Laming identified a need for fundamental change in the way that services for children and young people were delivered. Every Child Matters took up and developed this agenda – and the ‘5 ECM outcomes’ became a strong driving force in practice with young people in England.

Youth Matters (DfES, 2005) continued the ECM agenda, focusing particularly on the need to develop a coherent system of support for young people. Again, it highlighted the need for close working and collaboration across different agencies working with young people, including public sector, voluntary and community sector, and private, organisations. It placed a particular emphasis on supporting the needs of young people who were most at risk and who had the most complex needs, through the development of integrated youth support services and the role of the ‘lead professional’.

2.4 Partnership and policy drivers since 2010

Policy and practice in relation to partnership working and work with young people have taken a different direction since the election of the Coalition Government in 2010 and are increasingly different in different parts of the UK.

In England, as a result of changes in government policy and the global economic downturn, Alison Gilchrist observes:

… it appears that formal partnerships are losing significance in terms of strategic planning and resource allocation. The Localism Act 2012 downplays their role, scarcely mentioning the word ‘partnership’, and in many areas local strategic partnerships (LSPs) are being dismantled or becoming platforms for sharing data and airing views between different local government departments, other statutory services and the private sector. In the future, they are likely to have an increasing focus on enterprise and commissioning.

Cuts in funding for public services have also had a particular impact on youth services, with the BBC reporting that spending on youth services in England had fallen by 36 per cent between 2012 and 2014 (BBC News, 2014).

In other parts of the UK, policy has taken a somewhat different direction. In Wales, for example, the National Youth Work Strategy for Wales 2014–2018 highlights the role that youth work has to play in supporting young people to achieve their full potential, and the importance of partnership and collaboration between different organisations providing services for young people:

… statutory and voluntary providers need to take their collaborative working to new levels, maximising the impact of limited resources and presenting a high-quality and coherent offer to young people.

The Strategy also states that the Welsh Government wants to see a strengthening of the strategic relationship between youth work organisations and formal education, identifying that ‘Youth work interventions have been shown to have a positive effect on formal education outcomes, behaviour, attendance and progression through key points of transition’ (Welsh Government, 2014, p. 3).

In Scotland, policy continues to highlight the importance of effective partnership working in the delivery of services for children, young people and families and also sees youth work as having an important role to play in supporting young people’s learning and achievement. ‘Getting it Right for Every Child’ (GIRFEC) (2012) is a key policy initiative which is shaping and influencing policy, practice and legislation affecting children, young people and families at the time of writing. It emphasises the need for practitioners to work together, including ‘across organisational boundaries and putting children and their families at the heart of decision making’, in order to give children and young people ‘the best possible start in life’ (The Scottish Government, 2012, p. 4).

The Scottish National Youth Work Strategy 2014–2019, which has been informed by the GIRFEC approach, recognises the importance of youth work in improving outcomes for young people, including educational outcomes, and of partnership working as essential to achieving improved outcomes:

All young people, in every part of Scotland, should have access to high quality and effective youth work practice. This is what we believe and this is what we aspire to. We can only achieve this by working together with young people, Community Planning Partnerships, relevant organisations and other partners. We know we already have a great foundation to build upon. Changing the way public services are delivered is key to ensuring that young people continue to achieve the best possible outcomes.

We have taken you through a whistle-stop tour of some of the main policy developments that have influenced, and are influencing, partnership working in work with young people. You may well be familiar with a whole raft of other policy measures calling for partnership working based on your own experiences of practice.

Social policy is constantly changing; it is work in progress and subject to change as government changes. As we have seen, policy is also different across different areas of the United Kingdom, a trend which is likely to increase. Rather than provide you with a comprehensive guide to social policy, therefore, we indicate the need for you to be sufficiently informed about it to be able to take a critical stance.

The next activity asks you to think about your experience of partnership working and your knowledge of current policy drivers for partnership working in your own work context.

Activity 4: Your experience of partnership working

Make some notes describing your own experience of partnership working covering the points listed below:

- To what extent are you involved in partnership working in your current role?

- What organisations and agencies do you work with, and why?

- Thinking back to Himmelman’s model of levels of partnership working (networking, coordination, cooperation and collaboration), at what level would you place your own practice at this point?

- What are the key drivers in terms of policy that are encouraging or requiring you to engage in partnership working in your role?

Comment

We hope this has been a useful exercise, and one which has encouraged you to consider and share your own experience and to learn from the experiences of practice of others.

We are aware that, given the speed at which policy changes, some of the information that we have provided might already be out of date by the time you come to study this material.

One resource that you might find useful in helping you to keep up to date with changes in policy in relation to practice with children and young people across the different nations of the UK is the electronic briefing produced by the 4 Nations Child Policy Network. This provides a monthly round-up of significant child policy news, consultations, documents and legislation from all four nations of the UK. To subscribe to the UK e-briefing, send a blank email to uk-latest-join@childpolicylists.org.uk and then reply to the confirmation email you will receive (4 Nations Child Policy Network, undated).

2.5 The benefits of working in partnership

Partnership working is based on an assumption that ‘there are situations in which working alone is not sufficient to achieve the desired ends’ (Huxham, 1996, p. 3). We have already touched on some of the benefits that can come from working in partnership. We will now explore in a little more detail the benefits for organisations, for practitioners and for young people.

Activity 5: Thinking about the benefits of working together

Think about a partnership initiative that you have been involved in or are familiar with. In a table like Table 2 below, make notes in the right-hand column about the extent to which the potential benefits listed in the left-hand columns were achieved.

| Potential benefit | Was it achieved? |

|---|---|

| A spirit of competition was replaced by a spirit of cooperation. | |

| It released synergy and provided ‘added value’ – achieving more than either party could have achieved alone or working separately. | |

| It involved exchanging information and ideas, leading to improved decision making. It also helped to develop the knowledge and skills of different partners. | |

| It allowed for efficient use of resources. | |

| It provided a more holistic approach – partners were more able to provide support for the ‘whole young person’ rather than individual services addressing needs separately. | |

| It helped to ‘build capacity’ in the community by involving young people in partnership decision making. |

Finally, what other benefits do you think there might be from working with other people rather than on your own?

Comment

Some partnerships are inevitably more successful than others. However, it is useful to recognise the benefits that do come from working with others, and perhaps reviewing your successes will have reminded you of what you have achieved.

In thinking about the other benefits of partnership working, you may also have identified the potential financial incentives to working in partnership with other organisations. You might have found that it helped you to bid for and to secure joint funding – demonstrating an ability to work in partnership is often one of the criteria for the allocation of funding.

At its best, partnership working can provide practitioners with new opportunities for learning, as they develop their understanding of the way in which different agencies and professionals work, the skills that each can offer and the different perspectives that they bring. It is not just about sharing knowledge and experience, but also about bouncing ideas off each other, which can help to spark new ideas.

In order to realise these benefits, though, Chauhan (2007) reminds us that:

… such an approach requires the strengths of individual agencies to be drawn upon, an expectation that there will be mutual respect among key partners and an acknowledgement that what is at stake is local democracy not just the financial interests of individual organisations.

We have spent some time examining the benefits that come from working in partnership. We will now look at some of the challenges and dilemmas it can present.

2.6 The challenges of partnership working

Organisations are complex, as you will know from your own experience of practice and from your previous study. Partnership working – which involves different organisations working together – inevitably increases this complexity. As Huxham says:

Working with others is never simple! How often do we hear people say ‘It would have been quicker to have done this on my own’ even when there is only one other person involved? When collaboration is across organizations, the complications are magnified.

It is important to be realistic about these challenges if we want to be in a position to develop practical strategies for trying to overcome them. Next, you will read accounts from two practitioners whom we interviewed as part of the development of this course, in which they describe their experience of some of the difficulties of partnership working.

2.6.1 Difficulties in partnership working

Maria

Maria works as a youth worker for a voluntary sector environmental organisation. She has a wide range of experience of working in both formal and informal partnership arrangements and is very aware of the difficulties and potential pitfalls in working in partnership, including:

Different agendas. No clear role definition. Ineffective leadership – for example, not rotating the position of Chair, so the power balance stays with one agency.

Bureaucracy – with some agencies it wouldn’t matter who came on to the partnership board, they’re tied by so many restraints that they can’t really be effective within that partnership.

Funding. There’s a whole host of things that can go wrong.

Brona

Brona coordinates a young people’s health project. She also identifies difficulties she has come up against in her experience of developing joint projects with other agencies, including:

Different ways of working. Different values. Different funding streams. Everybody’s got their own agenda. People letting you down … Where the worker hasn’t turned up, they’ve let young people down; where they’ve broken confidentiality – all these things are crucial.

2.6.2 Differences in organisations

Different organisations have different aims, values and cultures. Some of these will be openly stated, others might be more subtle or hidden. In either case, differences in values and purposes can lead to arguments about what the partnership should be aiming to achieve, what will indicate success and how this can be evidenced and evaluated. It is also worth noting that some agencies may be working within different legislative frameworks which define their powers, their duties to provide specific services and the targets and outcomes that they are expected to meet.

2.6.3 Conflicts of accountability

Processes of accountability can be particularly complicated in partnership working:

… the individuals from the various organizations who are directly involved in collaborative activities need a fair degree of autonomy in order to make progress. The problem is that the activities of the collaboration will affect the ‘parent’ organizations, so the individuals also need to be accountable to the various organizations or other constituencies which they represent. Unless these individuals are fully empowered by their organizations to make judgements about what they may commit to, there will need to be continual checking back to the parents before action can happen. Much lapsed time can pass in this process, during the course of which impetus and energy levels for the proposed action can wither.

2.6.4 Differences in culture

Different professional groups also have different ways of working – including ways in which they perceive and relate to young people. Some professionals, for example, still see young people as ‘clients’, with the professionals holding the power (Sullivan and Skelcher, 2002), while others are committed to sharing power with young people and encouraging involvement in decision making. Some professionals may also hold stereotypical views about other professions, which can act as a barrier to communication.

All practitioners are brought up or accultured in one agency. The practitioner in a particular agency speaks that particular practice language, understands the roles and structures within that practice system and automatically and unconsciously sees the world from that single agency perspective. … What keeps us separate, both systematically and professionally, is very powerful and does not diminish over time.

2.6.5 Costs of partnership

While there may be financial savings from partnership, there can also be added costs. As Chauhan comments, ‘it takes resources and sustained efforts to establish, develop and maintain partnerships, whether these resources are in the form of money, time, skills, facilities or equipment’ (Chauhan, 2007, p. 239).

Networking and relationship building take a lot of time – a regular complaint of practitioners engaged in partnership working is that it involves lots of meetings – and time is money. Different organisations will have different levels of resources and capacity to engage.

Individual agencies may be fiercely protective of their own budgets. In addition, potential partners may also be potential competitors for funding, without which their own organisation might not survive. These sorts of pressures can act as strong disincentives to collaboration.

2.6.6 Conflicts and differences in power

The rhetoric of partnership working often emphasises sharing, cooperation and collaboration; the coming together of different agencies prepared to put aside their differences for the greater good of service users and communities. The reality of partnership may be very different. Partnerships can also involve conflicts and struggles for power – particularly when there are significant differences in the partners’ size, the resources they have available and their culture. Their past history of relationships between different agencies may also have an impact. Where relationships have been positive in the past, this bodes well for partnership working. Where there is a history of poor collaboration and mistrust, the task is likely to be more difficult.

Gilchrist (2007) points out that there is often informal wheeling and dealing between some partners, outside the formal partnership meetings, which excludes others from the decision-making process. Some agencies have more ‘clout’ than others. Those with power may be reluctant to relinquish it. What appears to be consensus may, in reality, reflect the dominance of the most powerful agency. Sources of formal power are complicated since a manager in one agency has no formal authority over practitioners in another agency.

For Balloch and Taylor, issues of power present the greatest challenge for partnership working, but a challenge that needs to be addressed: ‘If partnership does not address issues of power, it will remain symbolic rather than real’ (Balloch and Taylor, 2001, p. 284).

Activity 6: Exploring some challenges of partnership working

Watch the video, ‘Reviewing inter-agency work’, below which shows a meeting between Denise Godfrey, a youth officer with Wandsworth Youth Service whom you have seen previously, and Paul Howard, who works for the Youth Offending Team (YOT). They are meeting to review some joint work between the two agencies and admit that some conflict has arisen from trying to work together, but there have also been some successful outcomes for their partnership.

As you are watching the video, make a note of your response to each of the following questions:

- What joint working have they been involved in over the past 18 months?

- What have been some of the positive outcomes for the young people they have been working with?

- What does Paul say have been some of the advantages of working in a youth centre, as opposed to another venue – for example, one owned or managed by the YOT?

- Each agency would say that it ‘works with young people’, but they work in different ways and have different aims. Can you identify some of the differences between them? To what extent do you think that these differences have led to conflict?

- Why do they think it has been important to review and evaluate the partnership?

Transcript: Wandsworth Youth Service: Reviewing inter-agency work

DENISE GODFREY: Paul, can you just kind of remind me what the purpose of reparation is, as I understand that that's why the young people come here?

PAUL HOWARD: Reparation is where we look for young people to repair the harm done by their crimes within the community.

DENISE GODFREY: I thought this afternoon we'd spend a little bit of time evaluating the work that's been going on at the Resource Centre that's been delivered by the Offending Team and the work that we've done together. Maybe if we start with the poster project.

PAUL HOWARD: Yeah, we came down here to use the poster project, because the TRC was a good resource that had all the equipment we needed to produce the work we wanted with our young people within the poster project, where we get young people to consider their offence and then produce a visible idea of why they've committed the offence or the impact that that offence has had on themselves, maybe their family, and the community as a large.

DENISE GODFREY: We've stopped that particular project, or it's come to an end, so if we think about whether it was successful or unsuccessful, what the issues were that impacted on it.

PAUL HOWARD: I believe that the idea to bring it here was a good idea. Part of the problems we face by bringing young people involved in the youth justice system, the problem we might have had would be that there would be other young people surrounding them doing their own thing, which is really good, but our young people needed to be focused on what they wanted to achieve and that could be really distracting, and therefore, impacted on the work we really wanted to do. So the idea to pull the project after discussions with yourself was really valid.

DENISE GODFREY: Possibly we'd have to consider doing that outside of our normal opening hours.

PAUL HOWARD: I would think so, yeah. I would feel more comfortable with our young people being actually focused on the work they need to achieve.

DENISE GODFREY: Now if we move on then to think about the bike project. Now that does go on during the same time that the centre's open, so what's, what's making that different?

PAUL HOWARD: We work in another part of the building where we do the work which involves refurbishing bikes given to us by the community and by the police.

DENISE GODFREY: But is there any time maybe that actually the young people come into contact with the project other than when they're in there doing the bikes?

PAUL HOWARD: One of the things, again, one of the bonuses I feel about working with the TRC with yourselves is the young people who are involved in the youth justice system are quite often disengaged from the community and can often feel quite isolated. So by having the project here, we have that natural crossover where people can arrive early and are able to access other provision that you provide, such as the computers. They get information about drama projects, music workshops, so they're able to access. So therefore, there is that crossover and by working with your staff, they can also build up positive relationships with youth workers and other agencies. So I know that young people who are involved with me have certainly come on and come on to summer scheme programmes, have certainly take part in the music workshops and the computers.

DENISE GODFREY: Right, is there any other projects you might like to think about running from here?

PAUL HOWARD: We've run one other one if you remember, which is the cooking programme, where we have got young people to do cooking here where we've taken the goods on to disabled project within the community, so a real good positive link again where there...

DENISE GODFREY: ... Certainly, there was a spin off from there, because the young woman brings herself here independently now.

PAUL HOWARD: Excellent. That's one of our goals.

DENISE GODFREY: I feel overall the meeting went really well. It was a, it was a good chance just to reflect and think about the work that we've done together.

Initially early on in the project, there had been some conflict between myself and Paul around the issue of the poster project and of the young people using the room. And, you know, Paul was quite certain that he didn't want to have the young people in the room as much as I was certain that I did want to have the young people in the room, because I've got to look at resources and the use of resources. And should I open that room just for his young people during an evening session, it would be an awful draw on my resources at the Resource Centre in terms of hours of, of workers and also my returns at the end of the month that said there was only x number of young people in the Resource Centre. I was also dead keen, very, very keen, that the young people that came in who were on orders had an opportunity to get a real feel for what was happening in youth work, and in particular, what was going on in this centre.

So actually spending some time now some way down the line, it was quite good to be able to reflect on it, think about the project, and for me to recognise, well, actually that bit of the project didn't work, however, the rest of the project did and, and it was quite nice. So it brought to a closure in a way some of the issues that we'd had in the past, some of the confrontation between myself and that particular worker.

Comment

From watching the video, we can see that a number of difficulties and challenges have arisen as the two agencies have tried to work together. Paul works specifically with young people who have been offending and are ‘on orders’, a very particular ‘target group’ of young people. His work is focused on trying to reduce the risk of them offending again; he wants the young people to engage with specific activities that are intended to achieve this outcome.

As a youth worker, Denise’s work is informed by principles of voluntary engagement. She wants young people to be able to access the opportunities and resources that the youth centre can offer, including providing a space where different groups of young people can mix. But she also has targets that she needs to meet, including targets for the numbers of young people using the youth centre.

It seems that there has also been some interpersonal conflict which has sometimes made working together difficult. Poor interpersonal relationships and conflicts between individuals and groups may be a feature of some partnerships, and can create a significant barrier to effective partnership working. Put simply, if people get on together in partnerships, they are more likely to try to overcome some of the other barriers that might make it difficult to work together. Conversely, poor interpersonal relationships and conflict between particular individuals or groups can be powerful forces that undermine other factors that might be encouraging and supporting collaboration. As Gilbert (2005) observes:

The essential issue for partnerships, of course, is that it is based on relationships, both personal, professional and organisational. To gain partnership outcomes you have to work as partners – a simple truth which unfortunately escapes many people.

Despite the difficulties and challenges, Paul and Denise both remain positive about the benefits of working together. Paul can see the benefits of working in a youth centre, including encouraging young people he is working with to become involved with more constructive activities in their communities and to build up positive relationships with youth workers. Denise is pleased that one young woman, who was originally involved in a YOT project, has since started to come to the centre independently and become involved in youth work. Both comment on the usefulness of reviewing the way they have been working together, in part because it has helped to ‘bring to a closure’ some of the conflict between them and because it has reminded each of them of some of the positive outcomes of the partnership.

Given the long list of difficulties you might come up against, you might feel, as one practitioner we interviewed said, ‘Sometimes partnerships can be more hassle than they’re worth.’ Despite the challenges, however, we would argue that it is worth persevering and trying to find effective ways of working with others – if for no other reason than the reality that partnership working is unlikely to go away.

As Sullivan and Skelcher (2002) conclude:

The powerful momentum for collaboration is unlikely to be diminished, despite the problems of accountability, the complexities of the organisational relationships which emerge and the time and energy necessary to maintain these relationships at an organisational and individual level. The state is joining up with a vengeance.

Now that you are familiar with some of the benefits and pitfalls of partnership working, you should be better placed for thinking about the ways in which leaders – formal and informal – can maximise the potential benefits and deal with the difficulties. This is the focus of Section 3.

3 How can we make partnerships work?

In this section we move to examining approaches that you might take to developing effective partnership working in your own practice.

As we have already indicated, working in partnership covers a wide range of professional practice and organisational arrangements – which means that there can be no single blueprint or definitive guide to ‘making partnerships work’. However, we believe there are a number of strategies that can help you to engage effectively with partners, whatever your situation.

Reflecting on your learning about leaders and leadership, we would suggest that it is important for leaders to be good boundary scanners (being aware of what is happening outside your immediate working environment) and good boundary spanners (using the information you acquire about that wider environment to take a proactive approach to leadership, so that you are less likely to be constantly having to respond to crises).

Similar considerations apply in thinking about leading in a partnership scenario, although, inevitably, life is more complicated. Sullivan and Skelcher (2002) have listed a range of skills and attributes of effective boundary spanners, based on their research into partnership working. We present a modified form of their listing in Box 7.1 below.

Box 1: The skills and attributes of boundary spanners

- Critical appreciation of the wider environment.

- Understanding different organisational contexts.

- Networking – including knowing who the ‘right’ people are, being able to access them and having ‘political’ skills.

- Recognising the appropriate leadership roles to play.

- Partnership working skills, including:

- communication skills (verbal and non-verbal)

- emotional literacy skills (being able to ‘read’ the emotional climate and respond appropriately)

- influencing skills

- conflict resolution skills

- negotiating skills

- problem-solving and creative/lateral thinking skills.

- (Adapted from Sullivan and Skelcher, 2002, pp. 101–2)

One way of equipping yourself to recognise and tackle the potential challenges to partnership working is to consider your partnership within its wider context.

The next section, on ‘Partnerships in context’, examines the first three items on Sullivan and Skelcher’s list.

We then go on to consider how you might establish effective co-working agreements with your partners. Underpinning your work in all of the above are the partnership working skills, which we will also examine in more detail.

3.1 Partnerships in context

As a practitioner wanting to build relationships and work effectively with partners, it is important to understand the context in which a particular partnership is being developed. This includes making time to find out how different organisations involved in a partnership work and the factors that may constrain what they can and can’t do – for example, government policy or reductions in funding. You need to learn the terminology, to recognise the different meanings that people from different professional backgrounds might place on what appears to be similar terminology, identifying where the various sources of power lie, and so on. You also need to be aware of and be prepared to challenge the stereotypes that you may have of other organisations and professionals – and that they may have of you.

It might appear to be a daunting task. However, we are not suggesting that you should undergo a thorough research process on each and every partner or potential partner; simply that, in conversations with them, you find out what issues are on their mind and the significance of these for your partnership working. At a practical level, one youth worker whom we interviewed, who works for a voluntary organisation, offered the following advice:

You have to have an understanding of what current policy is, any contemporary developments you need to be aware of. There’s nothing worse than going to a partnership meeting and everybody knowing something that you haven’t really kept yourself up to date with. So always keep up to date and never be frightened to ask the question. If you don’t know something, ask somebody.

Alison Gilchrist (2007) emphasises the importance of informal links with your partners to complement the more formal meetings that you have, and argues that the most effective community leaders (using ‘leader’ in the informal rather than the formal, organisation-specific sense) are those who have strong informal networks, so that they are in touch with local concerns.

3.2 Co-working agreements

When working with a group of partners, it is important to agree an initial contract or set of ground rules in order to clarify what you each expect from each other and how you will work together. One of the stumbling blocks in partnership working is the assumptions that people may make about different elements of the work.

Gary, a detached youth worker, found that there were tensions between his team and the police. He highlights the importance of negotiating clear agreements before starting to co-work, and describes what he includes in such agreements, based on his own experiences of practice and what can go wrong.

Gary’s approach to partnership agreements

We sit down and clarify what is the purpose and the aim of the work. We would look at roles and responsibilities (as in who will do what and by when) and we would look to put in place regular meetings to reflect on what has been going on and to plan ahead.

We also look at how we would want to publicise anything we choose to do in terms of which names are getting mentioned, so that individuals do not claim all the glory … at planning in an end of project review [and] at the management structures. For example, if there were issues in relation to face-to-face delivery, which managers could or should be involved in unravelling some of those issues. At the end of the project we would produce a report where we would evaluate not only what we have produced but also what we have learnt from each other and the partnership working process.

We also negotiate partnership agreements on an individual basis. Even if I was co-working with one other youth worker from another discipline out on the street I would go through our code of conduct (in terms of how we operate on the street) before we began delivering together. For example, if young people use inappropriate language that co-worker needs to know what our boundaries are and how we deal with certain situations. There are also implications for us in terms of health and safety. As detached workers, when we are on the streets, our health and safety is always at the forefront of our minds. If we are taking workers from different disciplines they may not be aware of some of the importance of things like observation skills, constantly risk assessing, being in well-lit areas and being aware of what is behind you – the little things detached workers do instinctively.

(Gary, detached youth work coordinator)

One of the main advantages of written partnership agreements is that they provide a common reference point. As Gary says, much of our work may include things that we take for granted or that we do ‘instinctively’. When we are working with people from different professional backgrounds and professional cultures, approaches to work may need to be clearly spelled out and agreed.

One disadvantage may be that they might appear to indicate a lack of trust. Another may be that they give people less flexibility or room for manoeuvre. However, there is no rule about not renegotiating the agreement if it proves to be unhelpful and, again, having it written down provides a clear focus for this process.

The issues that need to be agreed will vary according to the nature and context of the work, but we suggest that issues to consider include:

- Your aims and purposes: including how success will be measured and what data might be collected, how and by whom. For example, you might need to collect data on the numbers of young people involved, for funders; or there might be information that you want to collect for your own purposes.

- Roles and responsibilities: who will be involved and who will be responsible for what.

- Meetings: how often you will meet and the purpose of these meetings.

- Codes of conduct: how you expect people to behave and treat each other.

- How you will deal with problems: including how you will communicate with each other if a problem develops between meetings.

- How you will review the work you are doing, including how you will evaluate your work at the end of the partnership if the partnership is likely to be time limited.

3.3 Partnership working skills

It is people who sit down together, not organisations, and how we perceive different organisations is influenced by the behaviour, personalities and interpersonal skills of those who work for them.

One of the complications of working in partnership is that there may be no formal leader:

Very often what is needed to catalyse collaboration are individuals who are able to ‘champion’ particular causes and motivate others to take collective action. … These leaders find themselves applying their leadership capacity in a new environment, one where hierarchies have been replaced by networks and inter-organisational reliance and it is not possible to lead simply by virtue of one’s formal authority in a unitary bureaucracy.

Many of the skills in partnership will be common to other areas of your practice. For example, good communication is key in partnerships, as it is in work with young people and colleagues. You have existing skills that you can build on.

3.3.1 Conflict resolution

… much of the skill involved in partnership work centres on dealing with problems, difficulties, conflicts and tensions.