Week 5: Introducing stakeholders

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 7:10 AM

Week 5: Introducing stakeholders

Introduction

In your work or volunteering – or other areas of your life – you may have noticed that some individuals and groups have quite a lot of power in how your organisation is run or how services are provided. Power means the potential to influence but whether people use this power will depend on what interest they have in influencing the organisation.

Some people have little power but a lot of interest in how the organisation is run and what it does. These individuals or groups could be service users, volunteers and employees, funders, the general public or the media, to name a few. These are some of the many stakeholders of an organisation, and they can be very influential in how an organisation meets its mission, how it’s viewed in the community, whether it receives funding, or how well it provides its services.

Last week you were introduced to the idea that an organisation needs to be transparent and accountable, and how the use of annual reports provides a way for an organisation to set out its financial position, as well as its achievements and challenges. Many of the people who need to know this type of information are an organisation’s stakeholders. This week you will explore the role and contribution of stakeholders to voluntary organisations.

There are many reasons why it is important not to neglect stakeholders: ensuring that people are consulted can help less powerful groups have a voice in decision making but equally, some groups may decide to campaign against a decision made by staff or trustees. These groups may be powerful enough – or rally enough support – to reverse decisions or to prompt resignations. A recent example of this is a community shop in south-west England where the community argued against the management committee’s decisions and all the committee members felt they had to resign.

This week you will think about the stakeholders of an organisation with which you are familiar, and you will explore the different perspectives they hold and the amount of power each has to influence how the organisation fulfils its mission. You will also learn about some of the ways in which voluntary and community organisations work and communicate with their stakeholders.

In the following video, Julie Charlesworth introduces you to Week 5.

Transcript

By the end of this week, you should be able to:

- describe the meaning of the term ‘stakeholders’ in the context of voluntary organisations

- identify primary and secondary stakeholders using different examples

- understand the competing interests in organisations

- identify how stakeholders may influence decision-making processes

- describe some methods for communicating with stakeholders in voluntary organisations.

1 Who are stakeholders?

The stakeholder approach to looking at an organisation’s priorities originated with business and management theories in the 1960s. The term stakeholders encompasses many different people and groups who have an interest in how well an organisation is run, including a business’s shareholders who obviously want a return for their investment. When we apply the term stakeholders to voluntary organisations, it has a similar meaning but the stakeholders are different.

Therefore, stakeholders are individuals or groups that have a ‘stake’ in, are affected by or can have an effect on an organisation. In the context of the voluntary and community sector, this often means those who have an interest in how well an organisation addresses the needs of its clients or service users – a key stakeholder group. However, if you look at the concept of stakeholders more closely, you will be able to identify other organisational stakeholders inside and outside the organisation: volunteers, board members and employees, for example, as well as donors, funders and policy makers. Stakeholders will often have different perspectives on an organisation – what its main priorities should be and how effective it is, for example.

1.1 Stakeholders in voluntary organisations

As you learned in Week 2, voluntary organisations and their missions are underpinned by values – values that you might assume are shared among an organisation’s stakeholders. However, this is not necessarily the case. Take a look at Figure 2. These are just some of the stakeholders you might be able to identify for a particular voluntary organisation.

This diagram illustrates primary and secondary stakeholders of a typical voluntary organisation.

This is a circular map with three levels. These levels are, from innermost circle to the outermost:

- The organisation

- Primary stakeholders

- Secondary stakeholders.

Different stakeholders are mapped onto this three-level circular map.

Mapped onto the organisation level are staff.

Mapped onto the boundary between the organisation and primary stakeholders are board members and trustees, and volunteers.

Mapped onto the primary stakeholders’ level are regulators; members and supporters; funders and donors; beneficiaries, clients and service users; and organisational partners.

Mapped onto the boundary between the primary stakeholders’ level and secondary stakeholders’ level are communities, and carers and families.

Mapped onto the secondary stakeholders’ level are government/policymakers; advocacy and interest groups; the public; similar or related organisations; professional associations; and the media.

The inner circle of the diagram – directly circling ‘The organisation’ – depicts the primary stakeholders. These are individuals and groups that have a direct, specific interest in how the organisation is run, its mission, its effectiveness and other day-to-day issues.

The outer tier depicts the secondary stakeholders, who may also have an interest in the organisation but perhaps not as directly or as specifically as those in the inner tier. Of course, secondary stakeholders can also take a direct interest – for example, in the case of organisational partnerships, the partners will want to ensure that partnership commitments are being upheld by the organisation.

Activity 1 Mapping stakeholders

Watch this video of Matthew Slocombe, Director of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), talking about his organisation’s stakeholders. Make notes on who the stakeholders are and then decide where they will fit on Figure 2.

Transcript

Comment

Matthew talks about the members being the core stakeholders so these would be put in the ‘primary stakeholders’ circle. Members pay their annual subscription and many actively participate. Although Matthew does not specifically mention staff, volunteers or trustees, these would be categorised as primary stakeholders.

Matthew also identifies local planning authorities, building professionals and the general public as stakeholders. In some cases, these groups approach the SPAB for information; in other cases, it is the SPAB who is targeting groups as part of campaigns to get the conservation message across. Local planning authorities and building professionals probably fit onto the boundary between the primary and secondary stakeholders. The general public are secondary stakeholders.

Activity 2 Mapping your stakeholders

Make a list of the primary and secondary stakeholders of an organisation with which you are familiar. This can be an organisation where you work or volunteer, or one that you have come into contact with in your community.

You might like to create a stakeholder diagram, similar to Figure 2 and Activity 1, to depict the stakeholders you identify.

What similarities and differences with the SPAB did you note and why?

Comment

You probably found both similarities and differences – depending on the size of the organisation you chose, as well as what field it is in (e.g. health and social care, environmental, hobby or sports and so on). You might also have found that Figure 2 made you think more widely about the people who might have an interest in your organisation.

These activities will have helped you think about who the stakeholders are in voluntary organisations. Next you will look at the power and influence different stakeholders have.

2 Stakeholder power and interest

Organisations depend on a number of stakeholders for their success and effectiveness. Funders, for example, have substantial power in determining how well an organisation can meet the needs of its clients and service users. Funders will also have a keen interest in how their funds are managed and in the effectiveness of the programmes they fund. As you saw in Week 3, some funding – particularly through contracts – is tightly controlled and monitored.

Activity 3 Keeping stakeholders happy

Read the following short extract from an article by Emma De Vita, a senior section editor on Management Today. While reading, think about how your chosen organisation responds to the interests of its stakeholders. Is it similar to the approach advocated by the author of this article?

As a manager of a stakeholder organisation, you have a responsibility to make everyone feel part of the decision-making process.

In practice, humans are often far too self-interested to make this happen in any meaningful way. Some stakeholders will be far more powerful than others, and it’s your job to work out who they are and butter them up to keep them happy. Then you’ll have those stakeholders who have little power or influence but who tend to be the most vocal. Keeping them happy is a headache in itself.

Charities, whose causes engender far more public interest than those of businesses (everyone cares about a homeless dog, but who has strong feelings about vacuum-cleaner production?), have a harder time putting [stakeholder theory] into practice. Public attention is the lifeblood of voluntary organisations, but it tends to make the number of concerned stakeholders skyrocket.

Keeping all of them happy would lead every charity chief executive to the edge of a breakdown. Better instead to console yourself with the axiom that, although all stakeholders are equal, some are more equal than others. Keep the most important people (those with the money) happy and placate the rest with free pens and newsletters.

Comment

Emma De Vita’s perspective on stakeholders may be cynical in one sense, but it fails to recognise the importance of secondary stakeholders. At the heart of stakeholder theory is the idea that organisations must make relationships with their stakeholders – both primary and secondary.

Speaking from a business and management perspective, theorist Freeman, et al. (2007) argued that even if a primary stakeholder (such as a funder) was satisfied, secondary stakeholders (such as an advocacy group) could still influence the relationship between an organisation and its primary stakeholders. In this case, a stable primary relationship could be jeopardised (or enhanced) by another relationship. Nevertheless, organisations will often need to choose how they engage with different stakeholders – most organisations do not have the resources to relate to them all.

It should also be pointed out that there may be different stakeholders related to different projects within an organisation, and that one of the challenges organisations face is to manage the different stakeholder needs and wants across various projects in the organisation. For many charities and organisations within the sector, the primary stakeholders are not necessarily funders. For example, for some membership organisations, members are the primary stakeholders. For many charities, service users are the primary stakeholders.

Moreover, many primary stakeholder groups (for example children) have little power in terms of getting their issues addressed, so organisations must be aware of the voice they give to certain stakeholders. Finding the right balance between competing interests and the level of power of each stakeholder group can be challenging.

2.1 Understanding power

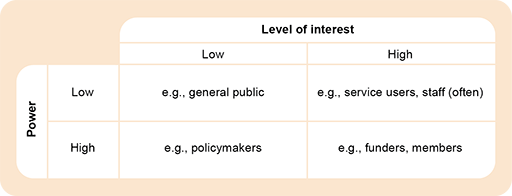

A method used to depict the relationship between a stakeholder’s interest in the organisation and the power they have to influence it is a matrix (see Figure 4). On this matrix, large-scale funders, for example, would be placed in the high interest/high power category. Similarly, an organisation might have stakeholders that have a high degree of power but little interest in the success of the organisation (for example policy makers). This might apply to some of the secondary stakeholders you identified in Activity 2. What about those with a high degree of interest but low power? Service users and staff in the organisation will often fall within this category, but not always.

This figure is a matrix table that provides examples of stakeholders with varying levels of power and interest in an issue or organisation.

Power is located along the y-axis of the table and is subdivided into two categories: low and high.

Level of interest is located along the x-axis of the table and is also subdivided into two categories: low and high.

This provides four cells within the matrix with the following designations and examples:

Low power/Low level of interest: e.g., the general public.

High power/Low level of interest: e.g., policy makers.

Low power/High level of interest: e.g., service users, staff (often).

High power/High level of interest: e.g., funders, members.

Activity 4 Power in practice

Create your own version of Figure 4 and use it to allocate the different stakeholders from the organisation you chose in Activity 2 to the different parts of the matrix.

Comment

This type of stakeholder mapping can be used for thinking about how organisations engage with their stakeholders. Allocating different groups within the matrix helps organisations to think about who has power and who should have more. Empowering groups, particularly service users and beneficiaries, is discussed in Week 6.

3 Working with stakeholders

Working with stakeholders can be a complicated process. As noted earlier, stakeholders can have competing perspectives on a voluntary organisation’s mission or how it does things, and it can be difficult to negotiate the differing levels of power and interest.

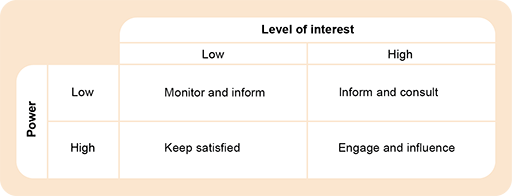

You can use the matrix in Figure 4 to think about possible strategies on how to work with stakeholders: this is depicted in Figure 6.

This figure is a matrix table that illustrates how you could work with stakeholders who hold varying amounts of power and interest.

Power is located along the y-axis of the table and is subdivided into two categories: low and high.

Level of interest is located along the x-axis of the table and is also subdivided into two categories: low and high.

This provides four cells within the matrix with the following designations:

Low power/Low level of interest: Monitor and inform.

High power/Low level of interest: Keep satisfied.

Low power/High level of interest: Inform and consult.

High power/High level of interest: Engage and influence.

Looking at the boxes now, you can start to think about methods of engagement:

- High power – high interest people must be fully engaged. This group is the one that organisations will work with closely.

- High power – low interest people need to be involved.

- Low power people with a high interest need to be kept well informed and consulted.

- People with low levels of power and less interest should be monitored but they may not want to become heavily involved in the organisation’s work.

Stakeholder theorists have identified a number of ways to manage the sometimes competing perspectives and interests of organisational stakeholders. Some of these strategies, identified by Mistry (2007), include:

- Addressing certain stakeholder perspectives adequately rather than in the best possible way (what is often termed ‘satisficing’, a blending of the words ‘satisfy’ and ‘suffice’).

- Addressing stakeholder issues over a period of time – rather than right away – in order to conserve resources (called ‘sequencing’).

- Balancing the needs of one stakeholder group with another’s so that both achieve at least partial success (what are known as ‘trade-offs’).

Managers and executives in the voluntary sector will often take a relative approach to dealing with stakeholders. Those who are the most crucial will receive the most attention, and as Emma De Vita stated in the extract you read earlier, ‘Keep the most important people (those with the money) happy and placate the rest with free pens and newsletters’ (2007). In the sometimes chaotic environment of the voluntary sector, an organisation may not have the time, staff or resources to pursue anything but this type of strategy.

However, other theorists argue that to focus on the needs of only the most powerful stakeholders is a poor strategy for overall effectiveness. In the business world, this means that business organisations need to focus on not only ‘creating value’ for their shareholders but also for other stakeholders (e.g. their employees and the community). In the context of the voluntary sector, where external stakeholders can play a much more powerful role, the organisation must balance the needs of its different stakeholder groups with the ability to address these needs amidst a scarcity of resources.

3.1 Managing stakeholders in the voluntary sector

As with many organisations, charities and other types of voluntary sector organisation will practise similar strategies to those just outlined. Certain groups’ needs can be addressed with minimal resources and services while the primary target communities will be supported with additional resources. A project may be designed to address one particular need among many, with partners providing ancillary or support services. Organisations may be dependent on other organisations in the sector to address stakeholders’ needs they are unable to meet – thus balancing their own independence with a wider range of services.

Activity 5 Brixton Splash

Read the following example of a street festival. Make notes on who you think the stakeholders are and what strategies (satisficing, sequencing, trade-offs) the organisers might have used when they first set up the organisation and to get the festival going.

Brixton Splash is an annual free street music festival in Brixton, London, which started in 2005. It is organised by a community organisation and uses volunteer stewards on the day. It currently has funding from the Arts Council and has had funding from Lambeth Council in the past. Its aims are:

- To promote and celebrate African-Caribbean heritage and culture, and its influence in the local area and beyond.

- To promote equality and diversity for public benefit through an inclusive festival that will foster understanding and harmony between people of diverse backgrounds.

- To advance education in music, arts, heritage and culture through a festival and outreach programme that will bring people of diverse backgrounds together for the appreciation and celebration of African-Caribbean culture and Brixton.

We celebrate our community’s diversity, its progress through the years and the fusion of numerous ethnic groups that now call Brixton home, by creating a cultural explosion proudly specific to our location and history. We successfully balance welcoming those who are just discovering Brixton with those who have always believed in Brixton’s unique identity, throughout the years. We remain loyal to and proud of our Afro-Caribbean heritage which has defined our community since the Windrush generation of the late 1940’s and 1950’s.

The Festival is a celebration of community cohesion, vibrant inner city living and Brixton’s contribution to the wider world. Brixton is currently the go-to area in London to enjoy everything culinary and creative with big name businesses moving to the high street and entrepreneurs developing the markets.

Lambeth is one of the most diverse boroughs in the country, with over 130 languages spoken. Brixton sits in the heart of the borough and is a bustling hive of activity. There is a strong history of music and the creative arts and numerous cultural groups are based in the area.

Our Festival is free for everyone, operates between midday and 7pm on the first Sunday in August every year and has become a premier event in the London Events Calendar.

Each year we improve and enhance the content of our event to build on its success and broaden its appeal.

Comment

The stakeholders include:

- the local community

- local businesses

- volunteers and staff

- Lambeth Council

- the police

- visitors to the event from outside the community

- sponsors.

Clearly, organisers of events like this must have to deal with a lot of competing interests. You may have thought of some of the following issues:

- Satisficing strategy: as live music is a major part of the festival, it might be that some local residents would not appreciate the music as much as others. These community members are still important stakeholders and so organisers need to limit the hours that live music is played during the day and into the evening – or where it is played – in order to avoid inconveniencing these residents.

- Sequencing strategies: these have probably been used as the festival has grown over the years. Available resources in the first years might have limited the number of stalls or services provided, and as resources grew, these services and events during the festival could grow too.

- Trade-off strategy: the organisers would need to collaborate with the Lambeth police and, in fact, in the early days of the festival the police trained the stewards. This would help to address a number of stakeholder interests: the community would be engaged in ensuring the event was safe, and local police would be able to ensure safety without a large police presence. Community members would see friendly local people if any problems emerged. In the early days of the festival, the organisers were keen to see the event move the community forward from its ‘infamous’ reputation of the 1981 Brixton riots.

As in this example, you might find that one or two of the strategies are particularly useful while others are best used at a different time or with a different set of stakeholders. However, it is useful to think about the different approaches you might take when working with a given set of stakeholders.

4 Communicating with stakeholders

Cartoon image of woman juggling balls while balancing on a tightrope. Under the image is the caption: balance your stakeholders’ needs.

A crucial strategy for engaging with, and managing stakeholders, is communication: among staff, managers and the board, between the organisation and its stakeholders and between the organisation and its funders. Such communication can help to coordinate work within the organisation and to build consensus on what makes the organisation effective.

Some common ways in which such communication is implemented are:

- annual reports and other publications provided to the public

- reports to funders

- periodic meetings with stakeholder groups (such as community meetings)

- regular meetings with and training of staff and volunteers

- annual meetings with members (such as in associations)

- fundraising events

- including stakeholders in the organisation’s strategic planning activities

- website and social media

- press releases

- service user and other stakeholder representatives on boards

- guest speaking engagements at meetings

- participation in collaborative project teams and task forces

- public testimony in government venues (such as local councils)

- conducting case studies with service users and beneficiaries of the organisation.

Some of these communication methods are more participatory and engage with stakeholders in a way that empowers them and gives them a voice. Other strategies are simply a means of communicating the main values and activities of the organisation and are less powerful. However, all of these activities are ways in which the organisation can communicate with its stakeholders, and manage its stakeholder relationships and the expectations of its stakeholder groups.

Each of the listed communication methods may address a different set of stakeholders. This is why managing stakeholders can be a very time-consuming process for organisations, and particularly for smaller organisations with few resources and staff time to spare. Nevertheless, managing stakeholder relationships and expectations is an important activity for voluntary organisations, which are often held accountable by their stakeholder groups for the services they provide.

Activity 6 Communicating with stakeholders at the SPAB

Watch Matthew Slocombe, Director of the SPAB, talking about communicating with stakeholders. Make a note of which methods the SPAB uses for which groups.

Transcript

Comment

Matthew highlights the need to use different methods depending on the group he is trying to reach. He mentions formal letters for local planning authorities as these are often used in the public domain (e.g. in planning inquiries or disputes): these would fit under the ‘public testimony’ category in the list above.

Matthew says seminars and conferences draw people in and staff attend events or meetings with people. He also discusses the problem of a ‘hard to reach’ group – the builders – who are often too busy to attend. The SPAB is trying different initiatives, such as involvement with colleges, so that they can provide information to trainees.

Activity 7 Good communication

Think of two different stakeholder groups for the organisation you are interested in. Then look at the different communication methods in the list above. Select two methods and investigate to see if and how they are used to communicate with the stakeholders. For example, you may wish to access the organisation’s annual report (if available), take a look at its website or follow it on social media.

If you had more time available, you could attend a staff meeting or a meeting of volunteers and take notes on how stakeholders are involved or their needs addressed. Another possibility would be to attend a community meeting held by the organisation.

During your investigation, take note of the following:

- How do you think the organisation seeks to manage the stakeholder relationships and expectations through the different communication methods?

- Which stakeholder expectations do you think are not addressed by the different communication methods?

Comment

You possibly found that a range of communication methods was used for each stakeholder group and these methods probably varied depending on the context. Social media, for example, is obviously very important for providing instant access to news stories, campaigns, announcements about meetings and so on. It can also be combined with other methods: for example, Calgary Zoo in Canada put their 2012 annual review on Instagram (Amar, 2015). However, if an organisation is looking to consult in depth, then face-to-face meetings might be particularly important but could be combined with generating discussion online.

In terms of not managing to meet stakeholder expectations, the context or specific examples you focused on will vary. Many people do not use social media so they may feel excluded and unable to participate.

5 This week’s quiz

Well done, you have just completed the last of the activities in this week’s study before the weekly quiz.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window (by holding ctrl [or cmd on a Mac] when you click the link).

6 Summary

This week you have learned about the different ways in which voluntary organisations address the needs of their stakeholders and that organisations often need to make difficult choices about how intensively they work with their various stakeholders.

Stakeholders can have differing levels of interest in a particular issue and widely differing levels of power to influence an organisation or project. Because voluntary organisations are often much more publicly accountable than organisations in the private sector, they often find it a challenge to balance the needs of their many different groups of primary and secondary stakeholders. Many organisations have scarce resources too, which adds to problems in communicating with all the groups. Organisations have a wide range of methods they can employ when communicating with their stakeholders in order to better manage their relationships and expectations. In Week 6 you build on the concept of power introduced here and examine a stakeholder group in more detail – service users and beneficiaries.

In Week 5, you have learned about:

- who stakeholders are

- the differences between primary and secondary stakeholders

- how to map stakeholders

- how power and interest can be mapped for different stakeholders

- some theories and methods of managing stakeholders’ competing interests

- methods of communicating with stakeholders.

You can now go to Week 6.

References

Acknowledgements

This week was written by Julie Charlesworth and Kristen Reid.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). For the avoidance of doubt: All third party videos credited below, and those which link you to Youtube for viewing, are not subject to Creative Commons licensing. Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this unit:

Course image: © Katie Hetrick in Flickr https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 2.0/.

Figure 1: Darren Whittingham/Shutterstock.com.

Figure 3: wavebreakmedia/Shutterstock.com.

Figure 5: Robert Daley/ Getty Images.

Figure 7: Faithie/Shutterstock.com.

Some content from this week draws on material by Kristen Reid from B191 Working in Voluntary and Community Organisations.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.

Copyright © 2015, The Open University.